“95 percent of Kashmiri Muslims do not wish to be or remain Indian citizens. I doubt, therefore, the wisdom of trying to keep people by force where they do not wish to stay.”

(An excerpt from J P Narayan’s letter to Nehru on May 1, 1956)

In the 18th century, the empire of the great Afghan conqueror, Ahmad Shah Durrani, included western Iran, Pakistan, Kashmir, and parts of northern India up to Delhi. Kashmir remained part of the Durrani Empire from 1752 till 1819, when it was conquered by the armies of Ranjit Singh. After the First Anglo-Sikh War of 1845-6 and the Treaty of Lahore, Kashmir was ceded to the East India Company which, in turn, sold Kashmir for the sum of Rs. 7.5 million to Gulab Singh, an influential noble in the court of Ranjit Singh, who subsequently became the Maharaja of Jammu and Kashmir and founded the Dogra dynasty which ruled Kashmir as a princely state under the British until Partition in 1947. The population of Kashmir comprised 77 percent Muslims, 20 percent Hindus, and 3 percent Sikhs and Buddhists.

At the time of Partition, the Two-Nation formula passed on Hindu territories and states to India and Muslim territories to Pakistan. However, there were complications in the case of three of the princely states: Junagadh and Hyderabad with Hindu majorities but Muslim rulers fell to India, but the fate of Kashmir with its Muslim majority and Hindu ruler was undecided. The Maharaja dismissed his prime minister, who had supported a third option — an independent Kashmir — signalling his intent to join India.

An insurgency began in the western part of Kashmir, which was supported by tribal militias from Pakistan. The Maharaja panicked and reached out to India for help. And in September 1947, he requested Nehru to accept his accession to India. Nehru set a pre-condition, that his dear friend, Sheikh Abdullah be released from prison. Abdullah was released, Mountbatten accepted the accession to India, and Abdullah became the first head of the Kashmir administration under India. India accepted the accession with the proviso that a referendum would follow as soon as peace was restored, since only the people, not the Maharaja, could decide where they wanted to live. But the referendum was never held. On October 24, 1947, a provisional government was formed in Azad Kashmir. On October 26, Kashmir was declared a part of India and a day later Indian troops occupied Srinagar.

The Kashmir dispute has led to four wars between India and Pakistan in 1947, 1965, 1971 and 1999 (Kargil). After the 1971 war, the Simla Agreement formally established the Line of Control that divided the territories controlled by the two nations. The territory of Kashmir remains divided — 55 percent is with India, 30 percent with Pakistan, and 15 percent with China.

As violence continued, India approached the UN for a resolution of the Kashmir dispute. On April 21, 1948, the UN passed Resolution 47 calling for an immediate ceasefire, withdrawal of Pakistani tribesmen from Jammu and Kashmir, reduction of Indian forces, followed by a plebiscite. The ceasefire was finally signed on January 1, 1949 by the two commanders-in-chief, General Douglas Gracey for Pakistan, and General Roy Bucher for India. The resolution called for Pakistan to withdraw first, and Indian withdrawal to follow; Pakistan refused, saying there was no guarantee that India would withdraw afterwards. In the end, no withdrawal was carried out and no plebiscite took place.

Pakistan took the opportunity afforded by the death of the powerful Nehru to launch Operation Gibraltar, a plan to infiltrate Kashmir and incite a rebellion against the Indian occupation

The conflict in Kashmir continued, and numerous plans and proposals to resolve the issues came to naught. A war ensued between China and India in 1962, in which China advanced but withdrew after a ceasefire. However, it retained Aksai Chin and the Trans-Karakoram area.

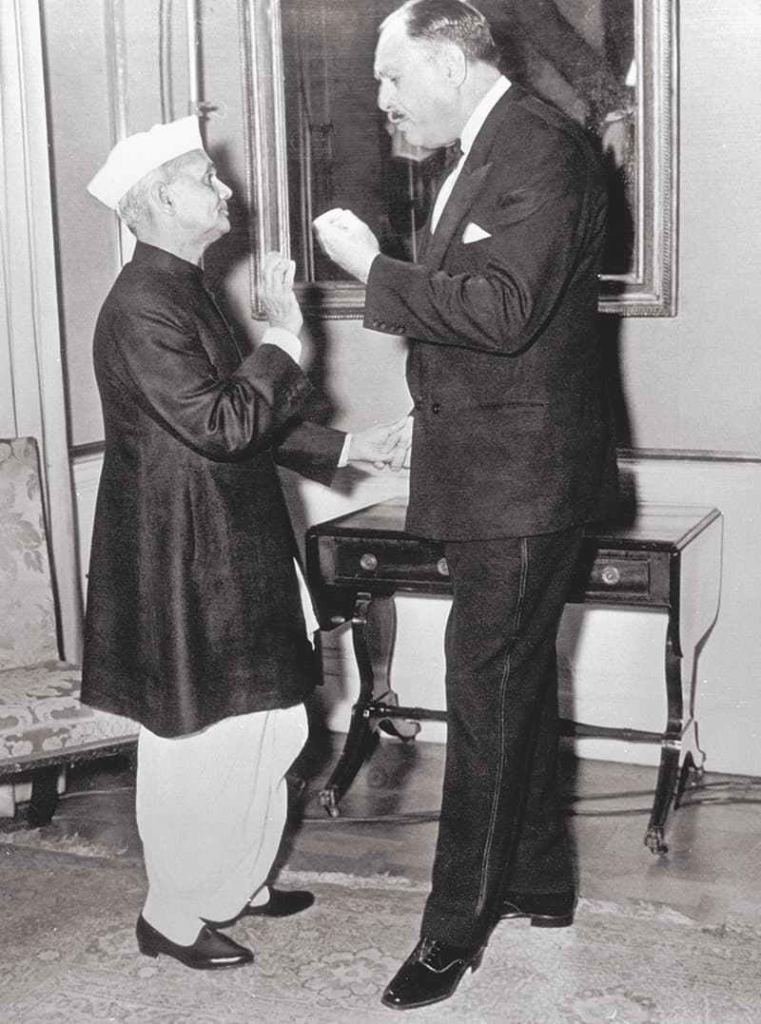

On May 27, 1964, Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru died. The new prime minister was a small, simple Congress Party leader, Lal Bahadur Shastri. Pakistan took the opportunity afforded by the death of the powerful Nehru to launch Operation Gibraltar, a plan to infiltrate Kashmir and incite a rebellion against the Indian occupation. The name Operation Gibraltar was chosen in memory of the Muslims crossing through Gibraltar in the conquest of Spain. Pakistan and its supporters in Kashmir built up a formidable position, but to their surprise India countered by invading the Punjab. Heavy fighting saw the greatest tank battle after World War II, but after 23 days, on September 23 a ceasefire was called.

An agreement was reached at Tashkent for both sides to withdraw to their pre-conflict positions and not to interfere in each other’s affairs. The tall, handsome and distinguished General Ayub, in his smart western suits, provided a stark contrast to the diminutive Shastri, in his simple homespun Indian clothes, but the two leaders gave each other respect and had a positive interaction. A day after the signing of the Tashkent Declaration, Shastri suddenly died. Headlines said a heart attack was the cause of death, but no post-mortem was conducted. At 3 am, the KGB arrested the butler, the cook, and three other assistants on suspicion of poisoning Shastri.

Shastri’s body was flown home. Lalita, his wife, was not satisfied and asked, “If it was a heart attack, why does his body have cuts? Why is blood dripping out? Why is his body swollen? Why has it turned blue-black in colour?” Kuldip Nayar, Shastri’s press secretary’s reply to her was, “I am told that when bodies are embalmed, they turn blue.”

The Indian Parliament constituted an enquiry committee and two key witnesses were summoned to give evidence: Dr Chugh, Shastri’s personal doctor and Ram Nath, his servant. Dr Chugh set off for Delhi by car; on the way his car was hit by a truck that killed both him and his wife. Ram Nath left Motilal Nehru’s residence for parliament but was hit by a vehicle on the way. His legs were crushed and later amputated. He suffered total memory loss and could not testify.

But the deaths did not stop here. Shastri was a supporter of India’s nuclear programme. On January 24, 1966, Homi J Bhabha, the father of the Indian nuclear programme who was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Physics, died when his aircraft exploded in Switzerland. Gregory Douglas, a journalist who investigated the air crash, wrote that the CIA was responsible for his assassination, which set back India’s nuclear programme. Five years later, Vikram Sarabhai, the physicist who initiated India’s space programme and also helped its nuclear programme, died in suspicious circumstances in a hotel. The Times of India wrote a story headlined, ‘Mystery behind Vikram Sarabhai’s death.’

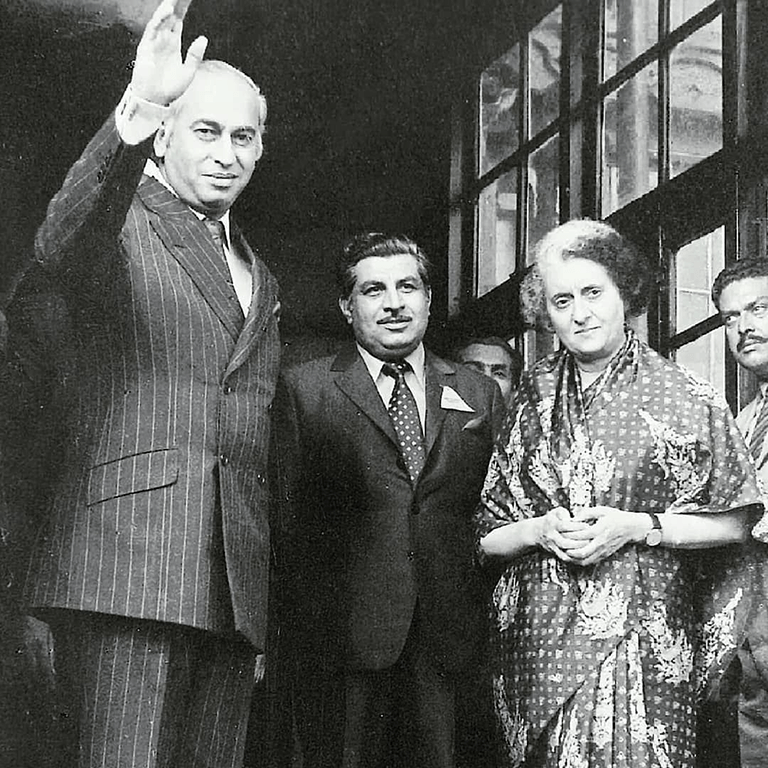

After the disastrous 1971 war that led to the creation of Bangladesh, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto and Indira Gandhi met at Simla. Bhutto wanted the repatriation of the 90,000 Pakistanis who had been taken prisoners of war (POWS); Indira wanted a durable solution to the Kashmir issue. An agreement was reached between them to avoid war, preserve peace, and observe the sanctity of the Line of Control, with India in control of Indian-administrated Kashmir and Pakistan in control of Pakistani-administered Kashmir. A second meeting was to follow, but it never took place.

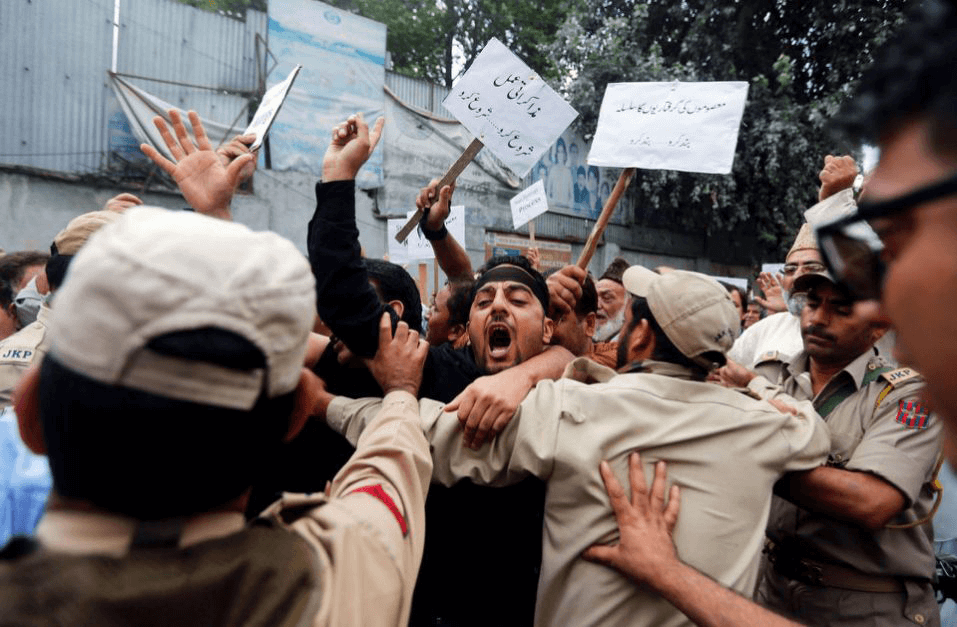

Bhutto tried to maintain the peace, but after his hanging, General Zia followed a different strategy. With strong US support to fight the war in Afghanistan against the Russians, Zia encouraged Islamist militants to become more active and aggressive in Kashmir. Violence escalated. In 1990, violence led to the mass exodus of the Hindu Pandits from Kashmir to safer territory in India, leaving only a few thousand behind. Indian repression in Kashmir grew harsher. Elections were rigged. An Indian Congress Party leader, Khem Lata Wakhloo wrote: “I remember there was massive rigging in the 1987 elections. The losing candidates were declared winners. It shook the faith of ordinary people in the elections and the democratic process.” Normal life in Kashmir disappeared.

In 1999, war broke out in Kargil. In the bitterly cold winters, it was the usual practice for troops to come down from the peaks since they did not anticipate any enemy attack. That year, Pakistani forces moved into the Kargil Heights to block the highway, the only link between the Kashmir Valley and Ladakh. In the battle that ensued, India recaptured most of its territory. This small war was disproportionately dangerous due to the fact that both India and Pakistan had proven nuclear capacity. Bill Clinton called on the warring parties to back off. War ended, but the confrontation that developed between then Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif and then Chief of Army Staff General Musharraf had far-reaching repercussions on Pakistan’s politics. Meanwhile, the Kashmiris were caught between the repressive Indian authorities and the harsh Islamist fighters and the mujahideen.

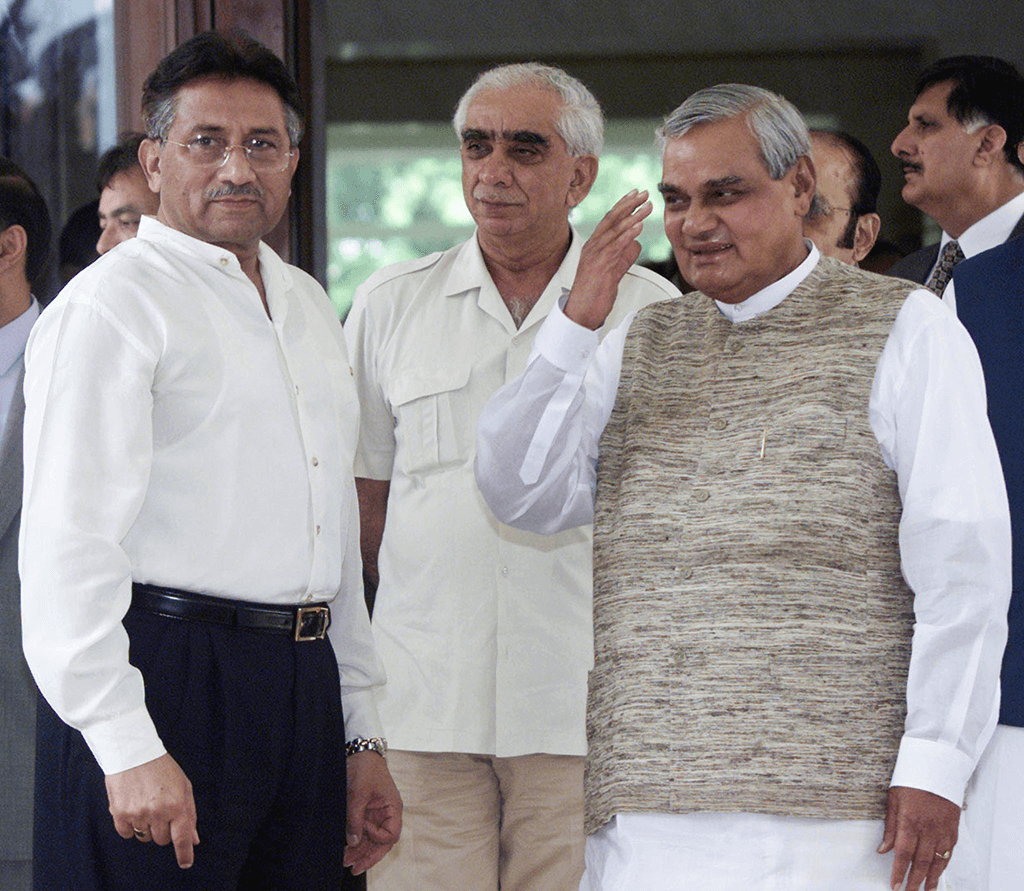

The war against the Russians in Afghanistan ended in 1989. This released fighters — and weapons — who were then sent to Kashmir; consequently the violence and repression increased; protests, armed struggle, police firing and curfews followed. Musharraf met Vajpayee for talks in Agra in 2001, but peace stood little chance when 38 were killed in an attack on the Kashmir Assembly in Srinagar in October 2001. Two months later, in December, the Indian parliament in Delhi was stormed. Musharraf continued his efforts for peace and restored the Delhi-Lahore bus service in 2003. In 2004, he met Manmohan Singh, the Indian prime minister in New York, but the meeting did not yield any conclusive results. The situation worsened, and in 2009 hordes of Kashmiris marched through Srinagar demanding independence. India called the fighters ‘terrorists,’ Pakistan called them ‘freedom fighters’ but it was highly embarrassing when then President Zardari, in an interview with The Wall Street Journal in October 2008, referred to the ‘freedom fighters’ as terrorists.

Kashmiris appear in no mood to yield. Against all odds, they have continued to resist the great Indian might

In 2019, Indian Prime Minister Modi sprung a surprise on Pakistan when it revoked the special status granted to Kashmir under Article 370 of the Indian Constitution and passed the Jammu and Kashmir Reorganisation Act of 2019. Now there was no going back. The Chinese response was to capture additional territory in Kashmir, which resulted in skirmishes between the two giants of Asia. Pakistan responded by announcing that Gilgit-Baltistan would become the fifth province of Pakistan.

Does this mean an end to the dispute? Most certainly not. There might be a covert push from the world and regional powers to make these three nuclear-armed neighbours accept their current disputed frontiers as permanent lines, but Kashmiris appear in no mood to yield. Against all odds, they have continued to resist the great Indian might. They will continue to fight as a grave injustice was inflicted upon them at the time of Partition by the departing British Raj and its successors in New Delhi. Accepting the disputed frontiers as permanent would also be a hard sell, especially for Pakistan’s civil and military leaders, to the majority of Pakistanis. Pakistan might take two steps back because of economic and international pressures for the time being, but it will never abandon the Kashmir cause. This means Kashmir’s cauldron will remain on the boil, and along with it the entire South Asia, threatening regional and world peace.