Pakistan’s 22nd engagement with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) — and its 15th since 1980 — i.e., its current Extended Fund Facility (EFF) programme for over $6 billion has resumed after a year-long temporary hiatus. Unlike many of the previous IMF programmes that got suspended or prematurely terminated because Pakistan could not keep up with the commitments (structural benchmarks, indicative targets) it made with the IMF, this time the programme was suspended on account of COVID-19.

IMF’s second quarterly review could not be concluded in February 2020, whereas the third, fourth, and fifth quarterly reviews could not be done due to the pandemic. These pending reviews were clubbed together and were completed in February 2021. A staff-level agreement was reached, and Pakistan’s case is being presented to the IMF’s executive board (probably by end March 2021) for release of the next tranche.

Originally, the IMF was supposed to provide over $6 billion under the 39-month programme ending in September 2022. A tranche of $500 million was to be released after every review. Thus, Pakistan was expecting a total of $2 billion for the four reviews (second to fifth) which got clubbed. However, instead of $2 billion, the IMF staff is seeking an approval of $500 million from its Executive Board — less than Pakistan’s expectations but at least it would keep Pakistan and the IMF’s current programme rolling. In fact, Pakistan’s engagement with the IMF enabled us to borrow, through the Fund’s rapid financing instrument, an additional $1.38 billion (over and above the EFF arrangement) for our COVID-19 response right at the beginning of the pandemic.

Subject to the Board’s approval, both the IMF and Pakistan have agreed to explore options, either to jack up the size of the tranches for the remaining reviews or extend the programme’s timeframe beyond September 2022.

This would also imply a fresh calibration of the macroeconomic framework, as the pre-Covid numbers and baselines agreed upon between the two parties are no longer relevant. Many of the reforms that Pakistan had committed to undertake may have to be put on hold (due to their transition costs to the masses) till COVID-19 recedes. Change in the reform calendar would imply a change in the EFF review schedule too.

It was not only our COVID-19 response that was dependent on the IMF. Unsustainable economies like ours are also in need of a seal of confidence from the IMF (a letter of comfort) to prove our creditworthiness to engage with other multilateral creditors. That is the context in which the resumption of the EFF was good news for Pakistan’s macroeconomic stability.

In the words of the IMF, “Pakistan has been facing long-standing economic challenges, including low revenue mobilisation, high fiscal deficit and indebtedness, low spending on education, health, and social programmes, and a weak external position (balance of payment, and foreign currency reserves).” The IMF further suggests that the above-mentioned economic challenges reflect the legacy of uneven and pro-cyclical economic policies in recent years aiming to boost growth, but at the expense of rising vulnerabilities and lingering structural and institutional weaknesses.” The IMF not only diagnoses the key challenges facing Pakistan’s economy, but also offers a prescription to address those challenges.

One of our chronic issues is the energy sector’s circular debt. The IMF wants the government to make the power sector financially viable by recovering the complete cost of energy. For this purpose, along with management improvements, cost reductions and recovery, and adjustments in tariffs and subsidies, it has asked for energy regulators, i.e., the Oil and Gas Regulatory Authority (OGRA), and the National Electric Power Regulatory Authority (NEPRA), to be given autonomy.

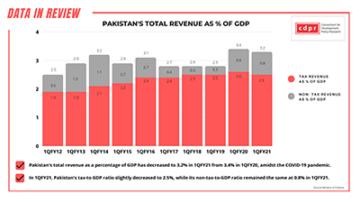

Low revenue mobilisation (read tax to GDP ratio) is another chronic issue denting our macroeconomic sustainability. It is a known fact that a narrow tax base, higher tax rates, and whimsical tax concessions are all problems that need to be addressed to avoid fiscal deficit. The IMF maintains that Pakistan needs to improve revenue mobilisation and ensure a more equitable and transparent distribution of the tax burden. In its opinion, to do the needful, the Federal Board of Revenue (FBR) should eliminate income and sales tax exemptions, reform the structure of corporate taxation to make it fairer and more transparent, and broaden the tax base to collect close to Rs. 5.9 trillion in the next fiscal year (One trillion rupees higher than the current year’s revenue target).

Loss-making state-owned enterprises is yet another issue confronting our economy. The IMF is stressing upon a comprehensive cost recovery and plugging of the fiscal haemorrhage of state-owned enterprises through better management, human resource rationalisation, and by following the principles of value for money.

Pakistan is fully committed to exit the grey list of the Financial Action Tax force (FATF). Grey-listing has no direct consequences on Pakistan’s borrowing ability from the IMF. However, its economic consequences could include higher costs of borrowing for the private sector on foreign financial transactions. The IMF has a structural benchmark that Pakistan completely address all the 27 action points prescribed by the FATF. Pakistan would not only have to address them to exit the FATF grey list, but also do so within a stipulated time period to meet the IMF’s indicative target.

Debt sustainability and transparency is another issue affecting our economy. The IMF has already been provided information on Pakistan’s public debt and loans from other countries (including China), in support of a comprehensive Debt Sustainability Analysis, which is a key component of an IMF-supported programme. Pakistan needs to ensure that its bilateral partners maintain their exposure throughout the EFF programme period and that the new financing is consistent with debt sustainability objectives. The IMF also emphasises that Pakistan remain within its pre-agreed primary deficit (difference between government revenue and expenditures, excluding interest payments).

The currency exchange rate, and the State Bank’s policy rate are the two major variables that, directly or indirectly, affect all walks of life. In six years (2013 to 2019), the State Bank sold almost $42 billion from its reserves in the open market to keep the conversion rate of the rupee against the dollar stable. On the advice of the IMF, the State Bank adopted a market-determined exchange rate. The IMF is asking for further autonomy for the State Bank of Pakistan, so that monetary policies remain unaffected by the federal government’s political considerations.

The IMF foresees that acting upon its advice, Pakistan would be able to free up resources for spending in priority areas such as health, education, human capital development and reducing poverty.

It is difficult not to agree with the IMF’s diagnosis of the challenges facing Pakistan’s economy. The Fund has been identifying these issues since 2008, when the PPP Government approached it for a Stand-By Arrangement (SBA). One can differ with the IMF’s solutions, as they seem to be prescribed over and over again, without bringing any long-term (or some argue, even medium-term) macroeconomic stability. However, the counter-argument arises whether the IMF’s prescriptions were ever implemented in letter and spirit at all.

Before moving forward, let us do a quick recap of Pakistan’s last two programmes with the IMF. In 2008, the PPP approached the IMF for an SBA amounting to $7.6 billion. The three major conditions imposed by the IMF for that SBA included reducing the fiscal deficit, levying value added tax and eliminating subsidies in the power sector. Fulfilling those conditions would have eroded the popularity of any government. So, like its predecessors, the PPP Government, too, in the run-up to General Elections 2013, prematurely terminated this SBA, holding down electricity tariffs, suppressing the fuel prices and adding to the fiscal deficit.

Economic challenges compelled the PML(N) government to approach the IMF in 2013 for a $6.4 billion loan. This was one of the rare engagements with the IMF that Pakistan successfully completed. However, the completion of this programme never translated into sustained macroeconomic stability. This was due to the fact that, with the political turmoil over the Panama Papers and some high-profile judicial verdicts, Pakistan had, once again, entered general election mode. Prime Minister Shahid Khaqan Abbasi’s government, too, had to resort to popular measures: holding down electricity tariffs, suppressing the fuel prices, relaxing the income threshold for taxation, and manoeuvring the currency market to externally stabilise the value of the rupee versus the dollar. All of those measures reimposed the economic challenges which further got aggravated due to the uncertainty surrounding the PTI government’s indecisiveness regarding whether to go or not to go to the IMF, during its first year in power.

Resultantly, Pakistan had to approach the IMF, once again in 2019, for the current EFF. The same old diagnosis, the same old prescription. The only difference was that this time the potency of the medicine (conditions and preconditions) has multiplied, and the relief (tranches of loans) would come in piece-meals.

Finally, let us examine how the resumption of the IMF programme, and implementation of its prescriptions for macroeconomic stability could hurt the microeconomic stability of the masses.

Elimination of the energy circular debt, through comprehensive cost recovery, and an autonomous OGRA and NEPRA would mean that regulators would not have to wait for the nod of the cabinet or the Prime Minister, before changing the price of energy. They would raise and reduce the domestic prices in keeping with the changes in international fuel prices.

An increase of 1 trillion rupees in the revenue collection target, without broadening the tax net, would mean that either the existing tax-payers would have to pay more, or the reliance would be on indirect taxes, which are regressive in nature and lead to inflation. Ending tax-exemptions and concessions would hurt certain influential interest groups, who would resist this change.

Plugging the fiscal haemorrhage of loss-making, state-owned enterprises would require revamping those organisations, staff rationalisation, public-private partnership, and or complete privatisation. The three major political parties tried to rule out these measures when they came to power, but vehemently opposed any such move when they were in the opposition.

One of the positive outcomes of Pakistan addressing the 27 action-points of the FATF is the renewed efforts towards documentation of the economy that is helping to bring informal economic activities into the formal regime. However, these measures are unpopular among certain interest groups, who are flourishing in the informal economic regime.

Due to weak resource mobilisation, the federal government had to start its fiscal year with a deficit. The federal share of the divisible pool is hardly sufficient to meet debt-servicing. All other expenditures (defence and security, pays and pension, subsidies and grants, and PSDP) are to be met through borrowed money. A cap on the primary deficit would mean that the government would have to prioritise debt-servicing over all other expenditures, most possibly compromising on the PSDP (Public Sector Development Programme).

A market-based exchange rate would make our imports (read petroleum products, palm oil, soybean oil, pulses, tea, etc.) more expensive, every time the rupee loses value against the dollar.

In the absence of any plan “B,” the only option left for Pakistan to achieve macroeconomic stability is to follow the IMF prescription in letter and spirit (and not lose its benefits through a spending-spree in the run-up to the next general elections). In the medium- to long-run, Pakistan would free up enough resources to be spent on social development. However, the cost of transition from the existing state of the economy to its macroeconomic stabilisation would be too high and must not be borne by the common man.

This would require a parallel strategy for social protection, which should help alleviate the effects of stabilisation on the vulnerable groups, particularly the poorest. Currently, there is a component to strengthen social protection measures in the EFF. This can be further beefed up by shifting from an “across the board” subsidy regime to “targeted subsidies.” The Pakistan Government is updating its National Socioeconomic Registry (NSER) for the Benazir Income Support Programme through a wellbeing survey. Triangulation of NADRA data with the wellbeing score of a household, would help in identifying those who should be getting the benefit of any targeted subsidy on a priority basis. Use of technology and data, in the tech-savvy “post-Covid” world, for reaching out to those who need to be protected in pursuit of macroeconomic stability, is the way forward.

The writer is Executive Director, Sustainable Development Policy Institute.