In many parts of the world, COVID-19 caused not just an economic downturn, but a severe food crisis, due to disruption in food supply chains. Pakistan’s economy, too, was hit by the pandemic. However, food supply chains remained intact and food availability, even during the peak phase of the pandemic, was not a matter of concern.

Having said that, sky rocketing food prices — especially the price of wheat — are irking both the government and the people of Pakistan. The masses find purchasing this staple item beyond their means while the government struggles to fend off criticism that it has been unable to control food prices.

With its 37 percent contribution to total food energy, wheat is not only the staple food crop for Pakistan, but it is an important pillar of food security. Reduced availability or increased price are important triggers for food inflation in Pakistan. During the ‘80s and ‘90s, Pakistan remained a net importer of wheat. However, since the year 2000, with a production of 24-26 million tons, it gradually turned self-sufficient.

Increase in wheat production in Pakistan is incentivised through a minimum support price (MSP). This is a pre-announced price at which provincial food departments and Pakistan Agricultural Storage & Services Corporation (PASSCO, a federal agency) procure 25-30 percent of total wheat produce, in order to maintain strategic reserves and ensure smooth supply of wheat flour at a stable price. The MSP for wheat crop 2021 was announced at Rs 1600/40 kg, which is 200 rupees higher than last year’s MSP. This is the sixth increase in MSP since 2008-09 when the PPP government fixed it at Rs 950/40 Kg.

Fixing MSP is a Catch 22 decision for any government. An MSP less than cost of production would erode the profitability of wheat farmers. On the other hand, an MSP on the higher side can trigger food inflation and erode the purchasing capacity of urban consumers. Thus successive governments have tried to watch the interests of both producers and consumers while fixing the MSP.

Whether the government should engage in the wheat procurement business at all and whether the MSP is the most efficient way of subsidising farmers is a moot point. In this regard, one should note a historical fact about the wheat MSP in Pakistan. The MSP has often been above international prices. The MSP of wheat in dollar terms plays an important role in determining how much wheat is likely to get smuggled out from Pakistan. From 2013 to 2017, the MSP was Rs 1300 per 40 Kg (US$315 per ton), reasonably higher than international prices. In theory this should have helped the government to restrict wheat smuggling to Afghanistan and beyond. On the other hand, the higher price compelled the government to provide a subsidy of US$90-120/ton (shared equally by the federal and provincial governments) to export surplus wheat.

Last year, despite the ban on wheat exports imposed in July 2019, the government exported 48000 tons of ‘surplus’ wheat. However, the exports were followed by an increase in domestic wheat prices. Here it is pertinent to mention that domestic wheat prices are controlled by the government through an ‘issue price,’ which is often a subsidised price at which food departments supply wheat to flour mills. Millers, in turn are bound to produce flour at a pre-agreed grinding ratio (of flour, bran and other by-products) and sell at a government-controlled price.

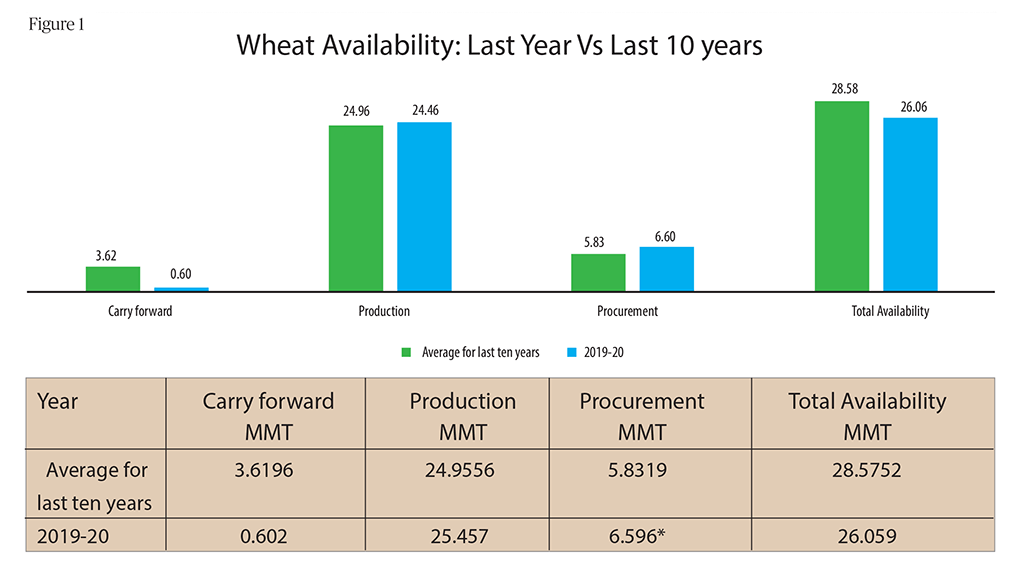

Coming to the abnormal increase in the price of wheat last year, an FIA enquiry report (April 2020) highlighted low carry forward stocks as a major reason for this price escalation. Last year’s carry forward stocks of 0.602 million tons (Figure-1) were 3.0 million tons lower than the ten year average of carry forward stocks (3.619 million tons). The Sindh food department did not procure any wheat last year, while the Punjab food department and PASSCO were unable to meet their respective procurement targets.

One was expecting the situation to improve with the arrival of a new wheat crop in April-May 2020. However, like the last few years, windstorms and rains during the harvesting season affected the standing wheat crop in Punjab. Low yield on the back of reduced wheat cultivation area (an expected 9.2 million hectares ended up at 8.5 million hectares) meant a shortage of wheat. It was officially announced that Pakistan missed its wheat production target by 1.6 to 1.8 million tons. This news alerted international wheat suppliers that Pakistan would be a captive buyer, resulting in an increase in international wheat prices.

Back home, to achieve its procurement target, the Punjab government did not allow traders and millers to purchase wheat from farmers at purchase points. They were allowed to enter the market only after the Punjab government had procured 4 million tons of wheat. However, by that time, the market had already dried up. The marketable surplus not purchased by the government had already been stocked by speculators hoping to make a windfall profit. Wheat prices in the open market had gone way higher than the MSP.

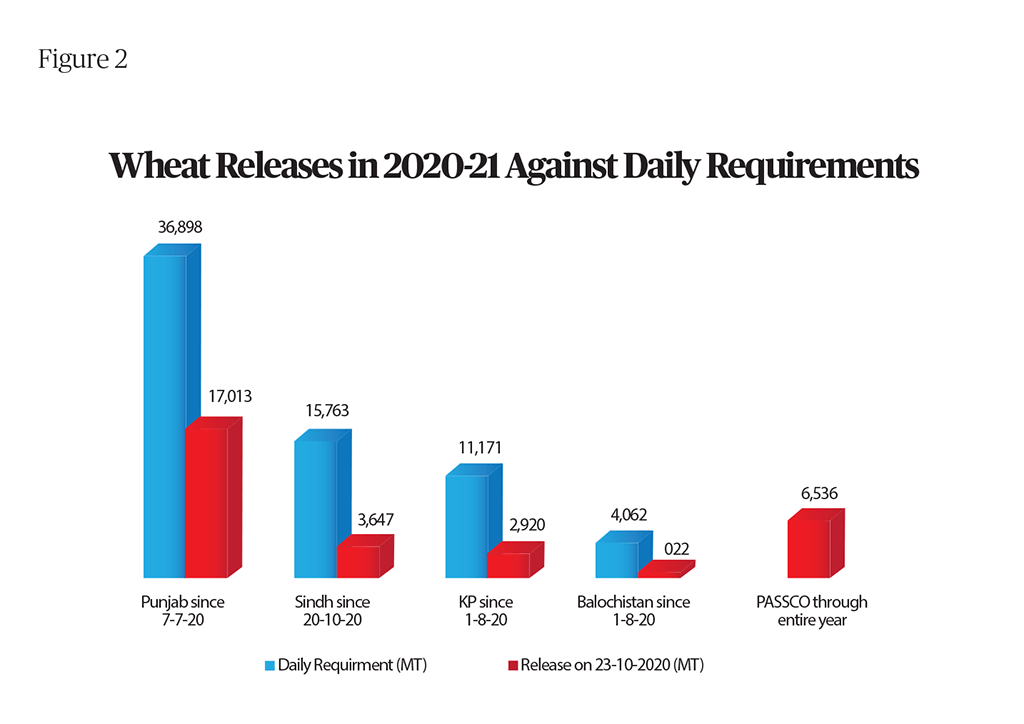

The millers went on strike and pressurised the Punjab food department to start releases from official storages in July 2020, a couple of months earlier than it would do normally. They also negotiated a lower grinding ratio. Earlier they were bound to produce 80 percent wheat flour and 20 percent by-products from the wheat they were getting from official storage. This year they are allowed to produce 65 percent flour and 35 percent by-products (15 percent reduced quantity of flour from subsidised wheat). The Punjab Food Department started releases at the rate of Rs 36.80 per kg and fixed the official sale price of flour at Rs 43 per kg. KP and Balochistan food departments started releases in August, while Sindh started its release from October 20 (Figure 2).

As figure 2 reveals, Pakistan’s daily requirement of wheat is around 73,333 tons. Punjab’s daily requirement is around 36,000 tons. The Punjab Food department is releasing around 16000 to 17000 tons of wheat per day to flour mills, but these releases are not enough to meet daily requirements. To meet the shortfall, millers have to buy an additional 20,000 tons of wheat per day in the open market, at a price much higher than the government issue price of wheat. It is not rocket science to infer that more than half of the flour produced per day in Punjab is bound to be sold at a price much higher than the controlled price, as it is prepared from expensive wheat; and there is an incentive for the millers of Punjab to sell the subsidised wheat in Sindh where the prices are much higher.

Depreciation of the rupee is another contributory factor to the wheat shortage in Pakistan. 2020’s MSP (1400 per 40 kg) equals US$ 223 per ton, whereas international prices have shot up to US$ 280 per ton. The price of wheat in Afghanistan is the PKR equivalent of 2550/40 Kg and wheat flour is PKR 3600/40 Kg. This price differential creates a huge incentive for hoarders to smuggle wheat to Afghanistan and beyond, resulting in shortage of domestic supplies. As told to the Senate Standing Committee, “Six million tons of wheat vanished during the harvest.”

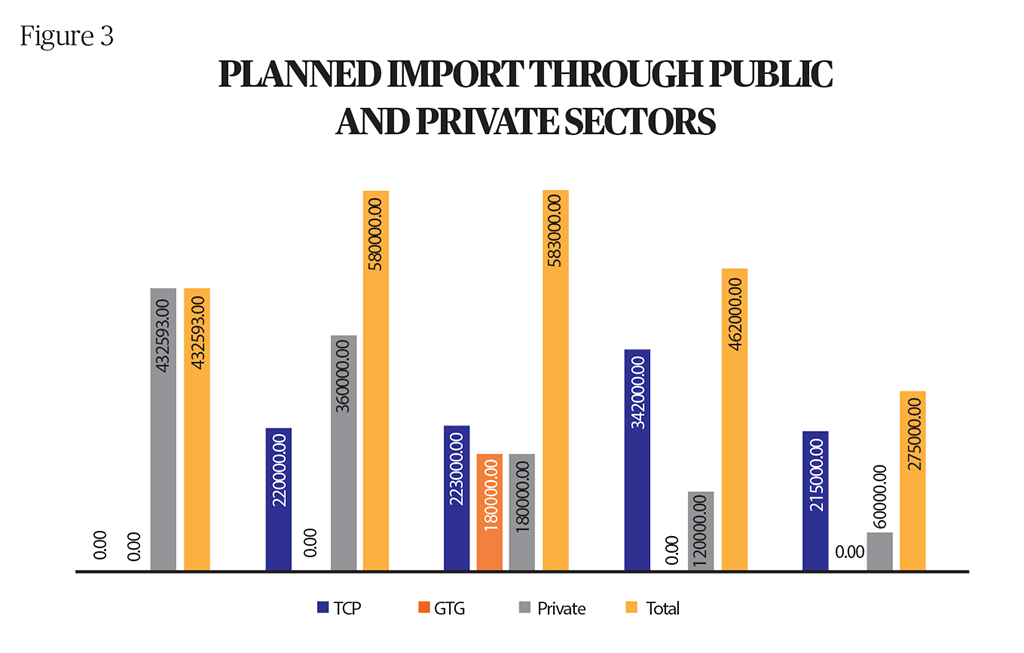

To meet the wheat shortfall, the government plans to import 1.5 million tons of wheat, while the private sector would import another 1.2 million tons. This would improve the supply situation. Improved supply may force the hoarders to bring out their wheat stocks, those that have not already been smuggled to Afghanistan. However, one should not expect that imported wheat would lead to a substantial reduction in the retail price of wheat flour (Rs 75 per kg against a control price of Rs 43 per kg).

The federal government has waived off all duties and taxes from import of wheat. Imported wheat would cost around Rs 50-52 per kg, add grinding, packing cost etc., and the price of one kg flour will exceed Rs 55. The government can subsidise to match the issue price, but the private sector cannot, and that will keep on distorting the market prices.

An unpopular way of reducing market distortion would have been to increase the government issue price (increasing subsidised flour prices) to bridge the gap between the government price and the open market wheat price. However, this would give a rallying point to the united opposition to criticise the government.

A truly out-of-the-box approach would be to abolish the wheat MSP that has created a wheat circular debt of Rs 757 billion against total stocks of Rs 320 billion, till December 2019. Abolishing MSP would also save the Rs 38 billion annual cost of buying, storing, and releasing 4 million tons of wheat in Punjab alone. The 450 billion to 500 billion rupees thus saved may be diverted to targeted subsidies for food security under BISP/EHSAAS, and/or to rigorously monitored distribution through utility stores. However, adopting this approach would be difficult for the government, as it would result in political backlash and erosion of PTI’s popularity in the rural constituencies of Punjab.

In the medium term, the federal and provincial governments should build their capacity for correct estimation of cultivated area and expected production in the country, to take evidence-based decisions.

In the long run, provincial and federal governments should either develop a foolproof system for tracing, tracking, and implementation of grinding ratio of subsidised wheat all over the country, or relax their control on wheat marketing and restrict themselves to maintaining strategic reserves.

All of these solutions require lowering of the political temperature and functional working relations between opposition parties and treasury benches. For this to happen, the government would have to invite its opponents to the negotiation table, which seems unlikely in the current polarised scenario. One needs to learn to live with the status quo, which is not only confined to COVID-19 and the resultant health and fiscal crisis, but also the food crisis that we have to face due to lack of political consensus on commodity market reforms.