The writer is the principal, School of Social Sciences and Humanities, NUST and Director General, NUST Institute of Policy Studies.

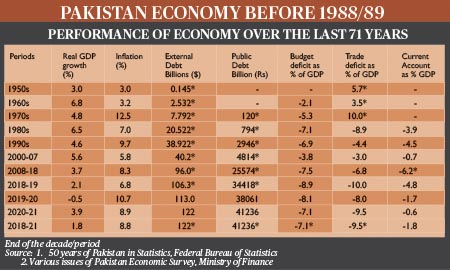

Pakistan has the distinction of being the only nuclear power which has sought balance of payments support from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) on a regular basis. In fact, Pakistan remains one of the nine prolonged users of IMF resources. Since 1958, Pakistan has gone to the IMF 22 times for bailout packages. However, since 1988 Pakistan has gone to the IMF 18 times with an increased frequency. Barring four years (2004-2008), Pakistan has been taking the same medicine from the same doctor for 33 years in a row, and yet, with each passing day the patient’s condition is deteriorating rapidly. In normal circumstances, the patient would have changed the doctor and the medicine, but it is indeed surprising that neither has the doctor been changed nor the medicine, despite the continuous deterioration of the country’s economic health.

Why does the country’s economy always deteriorate under the IMF Programme? To understand the mechanism, it is essential to understand the economic philosophy as well as the intellectual foundation of the IMF prescriptions. Are these policy prescriptions meant to improve the member country’s economy or to further weaken the economy? The reader should know that IMF policies are based on the intellectual foundation of ‘Neo-Liberal Economic Thought.’ Therefore, it is relevant to explain what neo-liberal economic thought is all about and what kind of order it remains committed to build and preserve.

The Neo-Liberal Economic Order is generally associated with policies of economic liberalisation including privatisation, deregulation, globalisation, free market, austerity, and reduction in government spending in order to increase the role of the private sector in the economy. This economic order gives little emphasis to the fiscal side, which is reflected in reducing the size of the government, cutting government spending, eliminating subsidies, removing price controls, and maintaining austerity in the government. The Neo-Liberal Economic Order gives a dominant role to monetary policy in economic policy-making. It is for this reason that the IMF has always asked for an independent Central Bank — free from the clutches of the fiscal authority (Ministry of Finance). Since monetary policy is the responsibility of the country’s Central Bank and its Chief Executive, the Governor is also a member of the Board of Governors of the IMF. Hence, the country’s macroeconomic policies shift towards the Central Bank and through the courtesy of the Governor, they shift towards the IMF. That is the reason that the IMF Programme’s implementers usually come from there as well.

There are two prominent Schools of thought of Neo-Liberalism — the Austrian School led by Friedrich Hayek and the Chicago School led by Milton Friedman. As the 1980s dawned, the term “Neo-Liberalism” became indelibly linked with the Chicago School where every economic problem has a monetary dimension, whether it is inflation or balance of payments. Therefore, these have to be addressed as suggested by the Chicago School. It is pertinent to note that the Chicago School or Monetarism has emerged as almost a “religion” of the IMF. All professional staff, after their graduation from any University, when they join the IMF, they adopt “monetarism” as their intellectual or institutional “religion.”

After the two oil shocks of 1973 and 1979, many developing countries faced serious balance of payments difficulties and accumulated huge debt. All these developing countries went to the IMF — the lender of the last resort — for financial support. The major Western powers, the United States in particular, decided that the IMF and the World Bank should play a significant role in addressing the challenges of developing countries. In the early 1980s, a consensus on a set of macroeconomic policies was developed among the three institutions, namely, the IMF, the World Bank and the United States Treasury for developing countries, to be implemented by them should they seek balance of payments support. A British economist, John Williamson, described the consensus as the Washington Consensus in 1989. The IMF has been made responsible for the implementation of the Washington Consensus through its various structural adjustment programmes. The Neo-Liberal Economic Order today is what is known as the Washington Consensus. The set of policies as enshrined in the Washington Consensus has remained invariant with respect to time, environment, and geography. History shows that such policies have seldom improved the economies of developing countries. Pakistan, Argentina, Chile, Ukraine, Egypt etc. are the classic examples where the IMF policies were implemented, but yet their economies have been weakening and debilitating their ability to take off.

What are the set of policies on which the Washington Consensus was developed among the three Institutions — the IMF, the World Bank and the United States Treasury?

The set of policies included:

a. Tight monetary policy (or raising discount/policy rate)

b. Tight fiscal policy (or cutting expenditure, eliminating subsidies etc.).

c. Market-based exchange rate (or devaluation)

d. Raising utility prices

e. Raising Electricity & Gas prices

From the IMF’s perspective, developing countries face balance of payments difficulties owing to excessive demand. Therefore, the IMF policies are also known as the demand management policies. The set of policies as listed above are meant to curtail excessive demand. The fatal mistake of the IMF policies or the Washington Consensus is that they treat both the economies of developed and developing countries alike. Problems in the developing countries originate largely from the supply-side, which the demand-side instruments remain ill-equipped to address.

For example, inflation in Pakistan is primarily a supply-side phenomenon coupled with government itself raising the prices of electricity and gas. The Central Bank invariably conducts tight monetary policy, that is, it increases the interest rate to curb inflationary pressure. Empirical evidence suggests that a one percentage point increase in discount rate increases inflation in Pakistan by 1.30 percent. Such policies, instead of curbing inflation, in fact give rise to stagflation. This is exactly what has happened in Pakistan. Economic growth nosedived while inflation hovered around double-digit levels. The bottom line is that the IMF policies are not consistent with the challenges faced by the developing countries. It is precisely for this reason that instead of improving the economies of the developing countries, these policies have compounded their difficulties.

Having said this, let me explain the economic implications of this set of policies.

a. Tight Monetary Policy means raising the discount or policy rate

An increase in the discount rate by the Central Bank increases inflation and seriously affects both the real sector of the economy as well as the country’s budget. It is well-known that an increase in discount rate increases the term structure of interest. The interest rates of all lending by commercial banks increase, thus raising the cost of capital. A hike in lending rates discourages private sector investment, it slows economic activity and reduces growth. Slower economic growth creates lesser jobs, leading to a rise in unemployment, poverty and social unrest in the country.

On the budget side, slower economic growth lowers growth in revenue collection. Furthermore, an increase in interest rates compels expensive government borrowing to finance the fiscal deficit from banks and non-bank sources, leading to a rise in interest payments, current expenditure as well as total expenditure. Slower growth in revenue collection on the one hand and the rise in government expenditure on the other, results in widening of the budget deficit, which leads to more borrowing to fill the revenue – expenditure gap. The rise in public debt comes as its natural consequence.

As a result of the rise in discount rate from 6.5 percent in June 2018 to 13.25 percent in July 2019 ( kept at these high-levels until February 2020), interest payments increased from Rs. 1,500 billion in 2017-18 to Rs. 2,750 billion in 2020-21 — an increase of over 83 percent in just three years. It may also be noted that the increase in discount rate during June 2018 to February 2020 (20 months), added Rs. 1,687 billion in interest payment in 20 months. Thus, an increase in the discount rate discourages private sector investment, slows economic growth, increases unemployment and poverty. On the fiscal side, it increases interest payments, current and total expenditure. Total revenue growth also slows as a result of slower economic growth, leading to a rise in the budget deficit and the attendant rise in public debt.

Empirical evidence in the case of Pakistan suggests that a one percent increase in the discount rate increases CPI-based inflation by 1.3 percent. Thus, the so-called tight monetary policy pursued to curb inflationary pressure, in fact, contributes to the rise in inflation. This policy leads to stagflation, that is, higher inflation and lower economic growth.

b. Tight Fiscal Policy

We have seen that by raising discount rates (tight monetary policy), the private sector is discouraged to invest more. Through tight fiscal policy, the government itself is spending less. Hence, both private and public sector are not spending enough, therefore, how can the economy be revived? Naturally, it slows economic activity, reduces economic growth, creates lesser jobs, increases unemployment and poverty; and therefore, becomes a great recipe for social unrest in the country as in the case of Egypt in 2011, where many related factors included unemployment, food price rises, low wages and corruption.

c. Market-Based Exchange Rate

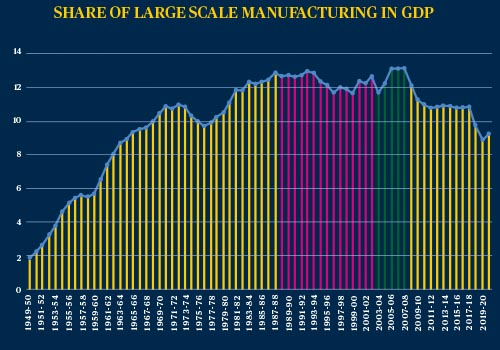

The so-called market-based exchange rate mechanism invariably leads to massive devaluation, which is, by definition, inflationary in nature and gives a justification to the Central Bank to tighten monetary policy by raising the discount rate. Very interesting! The country’s Central Bank devalues the national currency in the first place under the pretext of the market-based exchange rate. Since devaluation, by definition, is inflationary, it provides justification to the same Central Bank to increase interest rates. In the case of Pakistan, an increase in the discount rate increases rather than reduces inflation. Besides inflation, the devaluation increases the landed cost of all the imported inputs (like raw materials, machinery and equipment, oil and gas etc.) which increases the cost of production and along with higher interest rates (cost of capital), increase in gas, POL product and electricity prices, make the country’s industry non-competitive in the international market. Hence, it adversely affects the country’s industrial production and exports. Persistence of higher inflation forces the government to raise minimum wages. Hence, under the IMF Programme all efforts are being made to increase the cost of production, be it the imported inputs, utility prices, cost of capital and wages. The country faces de-industrialisation. Our Table clearly depicts the case of de-industrialisation (the share of large-scale manufacturing in GDP declining) in Pakistan that began since 1988-89 when it went to the IMF for balance of payments support. Over the last 33 years (barring four years (2004-2008)), Pakistan has remained under the IMF Programme 18 times, which badly affected its industries.

On the public debt side, devaluation increases public debt without borrowing a single dollar. In the case of Pakistan, a one-rupee devaluation adds Rs. 95 billion to the public debt (Public external debt amounts to $ 95 billion in end-June 2021) without borrowing a single dollar. With a weighted average interest rate of 4.0 percent, it adds almost Rs. 4 billion to the interest payment. How much cost has been added to Pakistan’s economy on account of raising discount rates and devaluation since July 2018? The calculation below summarises the cost.

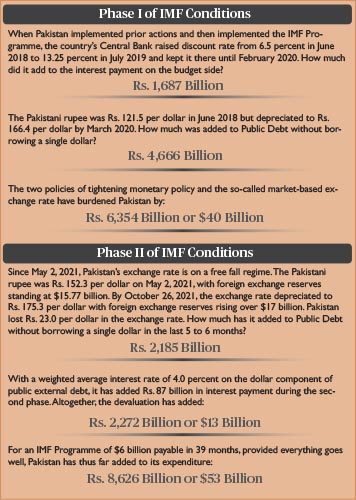

Phase I: When Pakistan implemented prior actions and then implemented the IMF Programme, the country’s Central Bank raised discount rate from 6.5 percent in June 2018 to 13.25 percent in July 2019 and kept it there until February 2020. How much did it add to the interest payment on the budget side?

Rs. 1,687 billion

The Pakistani rupee was Rs. 121.5 per dollar in June 2018 but depreciated to Rs. 166.4 per dollar by March 2020. How much was added to Public Debt without borrowing a single dollar?

Rs. 4,666 billion

The two policies of tightening monetary policy and the so-called market-based exchange rate have added

Rs. 6,354 billion or $ 40 billion

in terms of increase in interest payment and public debt in 21 months.

Phase II: Since May 2, 2021, Pakistan’s exchange rate is on a free fall regime. The Pakistani rupee was Rs. 152.3 per dollar on May 2, 2021, with foreign exchange reserves standing at $15.77 billion. By October 26, 2021, the exchange rate depreciated to Rs. 175.3 per dollar with foreign exchange reserves rising over $17 billion. Pakistan lost Rs. 23.0 per dollar in the exchange rate. How much has it added to Public Debt without borrowing a single dollar in the last 5 to 6 months?

Rs. 2,185 billion

With a weighted average interest rate of 4.0 percent on the dollar component of public external debt, it has added Rs. 87 billion in interest payment during the second phase. Altogether, the devaluation has added

Rs. 2,272 billion or $13 billion

In terms of rise in public debt and interest payment during the last five/six months.

For an IMF Programme of $6 billion payable in 39 months provided everything goes well, Pakistan has thus far added

Rs. 8,626 billion or $53 billion

In terms of the rise in public debt and interest payment in two phases, that is, in the last 40 months.

d. Raising Utility Prices

Under the ongoing IMF Programme, Pakistan has thus far increased the electricity and gas prices by 60 percent and over 200 percent, respectively. It has raised the utility cost of industries. Along with the imported inputs costs as a result of devaluation, interest cost owing to the increase in discount rate, hike in minimum wage and the rise in utility prices, Pakistan’s industries have become non-competitive in the international market which has severely affected overall industrial production and exports. Pakistan has been experiencing de-industrialisation since 1988/89, that is, ever since Pakistan has been under the IMF’s shadow.

Based on the above analysis, it is clear that the IMF Programme has damaged the economy and has created serious national security issues for Pakistan. The design of the IMF policies or the Washington Consensus is such that it causes investment to decline, slows economic growth, creates lesser jobs and gives rise to unemployment, poverty and social unrest in the country. It widens the revenue-expenditure gap which forces the government to borrow more to finance the deficit and gives rise to public debt. Furthermore, it transforms a low-cost economy into a high-cost economy through the hike in discount rate, devaluation and increase in utility prices.

As mentioned earlier, Pakistan has gone 18 times to the IMF since 1988. Dr. Ishrat Hussain, former governor of the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP), has described the decade of the 1990s as a lost decade for Pakistan in which it added $17.4 billion to external debt and liabilities. I have described the decade of 2008-18 as a second ‘lost decade’ in which we added $49 billion to the external debt and liabilities. There has been one thing in common in the two lost decades, that is, Pakistan has been under the IMF Programme. During the last three years (2008-21), Pakistan has added $27 billion to its external debt and liabilities. One more year is left for the completion of the ongoing IMF Programme and there are indications that the preparations are on to take Pakistan for yet another (23rd) IMF Programme starting September/October 2022, for three more years (2025). Can we afford yet another lost decade? I leave this to the people and to those who matter in this country to ponder on this development.

Recommendations:

There is still one year to go for the end of the ongoing programme. I will urge the Prime Minister, Finance Minister and those who matter that we have time to bring our external sector under control. Please pursue a selective and yet aggressive import compression policy. A Committee under the Chairpersonship of the Chairperson Tariff Commission may be formed with members from the FBR and Finance Division to identify fast moving, high value non-essential imports which can be curbed aggressively to save dollars. A dollar saved is a dollar earned.

Secondly, the government may set up a Permanent Commission on Import Substitution headed by the country’s leading industrialists with representation from the Ministry of Industries, FBR and Finance Division to identify products which are currently being imported but can be produced within the country with proper incentives and hand holding.

Thirdly, the government may float 5-, 10- and 30-years bonds in the international debt capital market, including in China to raise foreign currency to build foreign exchange reserves. The government may also consider floating convertible bonds for the said purpose.

Fourthly, the government must look into the deterioration in Pakistan’s agriculture, particularly as to what went wrong with the cotton crop and what is happening to the wheat crop. Pakistan has become a net importer of cotton, wheat and even sugar. We may take help from the Chinese experts under Phase-II of the CPEC, where agriculture is a priority area.

Fifthly, CPEC is a great opportunity for Pakistan in terms of industrialisation and export promotion. There is a strong view that the work on CPEC is not moving at a desirable pace. This misperception must be cleared, by speeding up the work.

The bottom line is that we must avoid at all cost going for the 23rd IMF Programme. Pakistan must learn to live without the IMF. Let the Prime Minister announce that there will be no 23rd IMF Programme. Let Pakistan live like other member countries of the IMF. There are 190 member countries of the IMF and only a handful of countries go to the IMF for financial support. There is no other nuclear power country that goes to the IMF on such a regular basis.

Yes, no more 23rd IMF Programme please.