Pakistan’s ballooning population growth is the biggest challenge the country faces in 2021 and beyond. The mother of many key problems, it will push the unemployment rate higher, make water availability scarcer, threaten the country’s food security with a reduction in cultivable land, and intensify the problem of malnutrition and stunted growth among children, if it remains unaddressed.

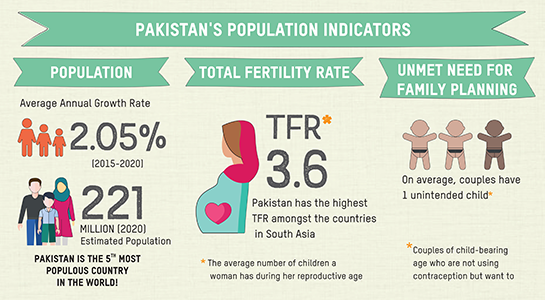

Indeed, Pakistan’s population growth at 2.05 percent per annum is a proverbial ticking time bomb, which successive governments have never placed high on the priority list, merely to appease the hardline religious groups and placate conservative social and cultural attitudes. This unbridled population growth has made Pakistan the fifth most populous country in the world and has the potential to sharpen and worsen its social, economic and political chasms, further intensifying unrest, disorder and violence in society.

Pakistanis add four to five million people every year to their population, which is equal to the size of the entire population of New Zealand. There has been a six-fold increase in Pakistan’s population from 34 million in 1951 to 220 million plus in 2020, according to UN estimates.

Pakistan’s population growth rates are higher compared to other Muslim countries including Bangladesh, Indonesia, Iran, Morocco, Malaysia and Turkey. According to a UN statement on New Year’s day, 14,161, babies were born in Pakistan as compared to 12,336 in Indonesia, 9,445 in Egypt and 9,236 in Bangladesh. The comparison with Bangladesh, in particular, should be an eye-opener. In 1971, Pakistan’s population (West Pakistan at that time) was 66 million, while East Pakistan’s (now Bangladesh) was 68 million. In 2020, Pakistan’s population is more than 220 million while Bangladesh stands at 165 million.

According to figures compiled by the Population Council — an international NGO focused on research on population and health issues — if Pakistan’s population continues to grow at two percent per annum, it will face the foremost challenge of food security, due to the shortage of cultivable land. The current availability of cultivable land at 1.3 square kilometres per 1000 rural persons will further reduce to 0.8 square kilometres by 2040.

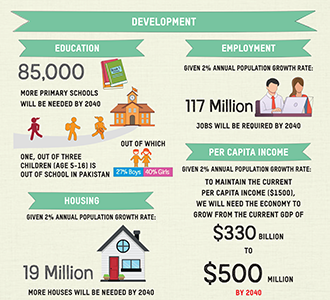

Furthermore, at the current population growth rate, the Council estimates that Pakistan will need 85,000 more primary schools, 117 million more jobs and 19 million more houses over the next 20 years.

Already Pakistan is lagging behind on all three fronts — one out of every three children aged between 5-16 is out of school, the number of unemployed is hovering at 6.65 million and the shortage of houses is roughly around 10 million units.

Even to maintain its current per capita income of around $1500, Pakistan needs to almost double the size of its GDP from $276 billion to more than $500 billion.

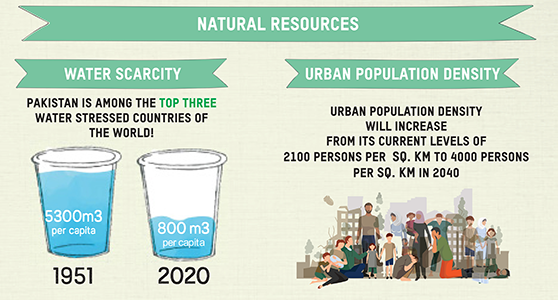

Water scarcity is another major area of concern as Pakistan is already ranked among the top three water-stressed countries of the world. In 1951, surface water availability per capita was 5260 cubic meters per person, which has now fallen to less than 1,000 cubic meters per person. If this situation persists, by 2030 Pakistan will fall in the category of water-scarce countries.

A rapidly growing population means an ever-increasing demand for food, water, schools and colleges, hospitals, houses, jobs and infrastructure. Can the state increase its resources to match the rapid surge in demand for its resources?

Experts maintain that access to family planning remains a major issue for the poor, especially in rural areas. Health facilities, including those in the private sector, are located mostly in urban areas; therefore, the urban poor has better access to family planning. But according to the Population Council, the rural poor “have to travel four times the distance to access FP (family planning) facilities.”

Women plagued with poverty, curtailed mobility and little decision-making power suffer the most. One of the brochures of the Population Council states that maternal deaths can be reduced to 4,900 annually from the current 12,000, if contraceptive use rises by 35 to 55 percent. But achieving this target is a tall order.

High fertility also results in malnutrition. Forty percent of the children under the age of five are stunted, 18 percent wasted and 29 percent are underweight.

What went so drastically wrong in Pakistan, which was the first country in Asia to launch a family planning programme way back in 1960?

The answer can be summed up in just two words: political expediency.

It was in General Zia-ul Haq’s 11-year tenure, that family planning efforts were put on the back-burner and have remained there since, despite the on-and-off lip-service paid to the cause by successive governments, both elected and unelected.

The influence of hardline religious groups and conservative elements in society is evident from the fact that the authorities have abandoned the slogans of small families like, “Bachay, dou hee achay” (Two children are better) or “Kum bachay, khushhaal gharana” (Few children, prosperous family) altogether. Instead, now the messaging is toned down, urging people to maintain gaps between births or asking them whether they can afford proper education, healthcare and nutrition for their children. But this tack, which the authorities say is aligned to the sensibilities of the majority of Pakistanis, does not seem to be working.

If on the one hand, religious and cultural taboos serve as a stumbling block in family planning, on the other hand it is the lack of commitment and political will on the part of successive governments, which is amply demonstrated by the absence of birth control facilities for the majority of Pakistanis, especially in the rural areas.

What the country desperately needs to curb population growth is efforts on a war-footing, which means both advocacy and on-ground facilities. Unfortunately, we are lagging behind on both these fronts. An organised, focused and aggressive national strategy is nowhere to be seen.

Pakistan needs greater political commitment and cross-party consensus to ensure that the federal and provincial governments are meeting the family planning needs of the people. Also, the policy-makers have to not only ensure that family planning is part of the national discourse but also allocate sufficient funds for it.

Will 2021 be any different from 2020 when it comes to curbing population growth? Up until now, the winds of ‘Naya (New) Pakistan’ do not seem to have blown this way, as the population figures continue to mount. n