While most of my friends aspired to join the civil services, I gravitated towards a stable life; so I became a banker. But my life as a banker was to prove far from stable. I joined UBL, a bank set up by the amazing Agha Hasan Abedi. He was unlike other men and his banks were distinct from other banks. I became manager of the Islamabad branch of UBL, and when in Islamabad, Agha Saheb would, on occasions, drop by my branch for a coffee.

When Pakistani banks were nationalised by Bhutto, I followed Mr. Abedi into his new international bank, The Bank of Credit and Commerce International (BCCI), which he created with the support of the legendary Sheikh Zayed of Abu Dhabi. In the 1960s, before the oil boom, Zayed visited Pakistan with his hunting falcons and his Bedouin followers. He was not so well known then and not as phenomenally rich as he was later to become. Needing some spending money, he asked Habib Bank Ltd (HBL) for a small loan, which the conservative HBL declined. Abedi seized the opportunity and lent the Sheikh whatever he needed, thus building a relationship that would later shake the banking world.

Agha Hasan Abedi was a master in the art of building and nurturing relationships. He built his banks on relationships with his investors, with his clients, and with governments which are the key to the growth of a bank. Governments are run by people, and Abedi knew only too well how to seduce powerful people. He trained us, his managers, in this art — a new style of banking. As the bank spread its tentacles around the world, we, his disciples, set up new branches and new banks in country after country. I moved from London to Panama, and then on to Washington and Miami.

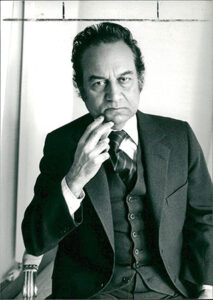

The partnership between Agha Hasan Abedi (left) and Sheikh Zayed

became the foundation of a banking superpower.

Miami was very different from other American cities. Known as the capital of South America, it had attracted the sugar barons of the Caribbean, who had arrived in the late nineteenth century and built their huge estates and mansions on the fabulous beachfront. They were followed by hordes of Latino immigrants, who made Miami their home, giving it a distinctive Hispanic flavour. The top financial district was carved from the mansions of the sugar barons, and the BCCI office was located in the tallest and most glamorous black glass building on Brickell Avenue. Mr. Abedi believed in style and in every major city around the world, his bank’s offices stood out as the pinnacle of glamour and style. From Miami, my job was to spread the bank’s operations in the exciting countries of South America: Colombia, Brazil, Venezuela, Panama and many others.

On my trips, I met many high net-worth individuals as prospective clients for the bank. In Colombia, once we were taken to meet a lady reputed to be fabulously rich. We were received at the airport in a shiny new Mercedes but en route we changed cars several times — from Mercedes to Jaguar to BMW to Audi. Finally, we reached her magnificent mansion where a gracious young man received us and took us to meet his mother, an elegant lady in her 50s. After a sumptuous meal that I will never forget, she took us on a tour of her estate which ended in her operations room, which seemed to be straight out of Star Trek, with its wall of TV screens showing her operations across the world, tracking her ships, cargoes, and trucks as they moved. We beat a hasty retreat and scratched her name from the list of potential clients.

In Venezuela, we established a Representative Office but failed to get a full banking license. I was sent to investigate the problem. Our country representative was a serious but unsophisticated officer, who didn’t really fit in with the international banking scene. One night, he drank too much at an important reception and made a pass at an elegant lady, who turned out to be the Superintendent of Banking. She said that the BCCI would never get a license as long as she remained Superintendent. I reported the problem to London and I was instructed to issue his termination letter, despite the bank’s policy of never dismissing any employee.

I made many fascinating trips, travelling first class, and stayed at 5-star hotels in the fabulous countries of South America, but it was Panama that was to change my life. Panama was famous for its canal, which had been built by the US at the beginning of the twentieth century. A wide swathe of land on either side of the canal became US territory; locals were effectively kept out and the US controlled the administration, courts, police and currency in the Canal Zone. By the 1960s, the Panamanians had become resentful of US control and riots started to destabilise the canal. On September 7, 1977 President Jimmy Carter and Omar Torrijos, the Panamanian strongman, signed a treaty under which control of the canal would return to Panama on December 13, 1999.

BCCI wanted to open its operations in Panama but attempts to obtain a banking license failed repeatedly due to the influence of the powerful US Banking Association in Panama. When Omar Torrijos, the Panamanian strongman, wanted to visit London, the Ambassador of Panama in France, who was a friend, asked me to look after him on his trip. The bank saw this as an opportunity and we arranged a luxury apartment for him in Mayfair plus cars etc. and made sure he lacked nothing. I requested Mr. Abedi to call on Torrijos at his apartment, but when Mr. Abedi learned that Torrijos was not the president, he declined, saying he only called on Presidents and Torrijos would have to call on him! I explained to Agha Saheb that Torrijos makes and breaks presidents and is himself more powerful than any president. Agha Saheb relented and made the visit. The bank developed a relationship with the strongman and followed up with a visit to Panama to make one more attempt to secure a license. It proved only too easy, and we were allowed to start our banking operations in Panama.

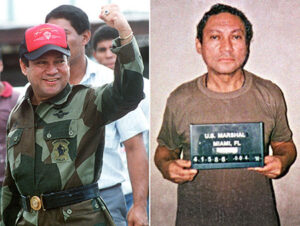

I was appointed country manager for the bank in Panama in 1980, but a year later, Torrijos died in a plane crash. His chief of intelligence was the crafty pock-marked colonel, Manuel Noriega, who soon emerged as the new strongman. Noriega was close to the CIA and was considered ‘Our man in Panama’ before he was ousted and imprisoned in the US. I met Noriega as country manager in Torrijos’s Panama, and we became friendly. I was to host his visit to London later.

I looked after both Torrijos and Noriega on their London trips, but it was to two different Londons. Torrijos was a simple man, interested in museums, particularly military and war museums. He would look at Harrod’s from the street and not venture into its extravagant shopping halls. Noriega was into fancy restaurants and sexy night clubs; he was thrilled by the new Regine’s nightclub on the roof of Derry & Toms in Kensington. Whatever their tastes, the bank made sure they each enjoyed a trip to remember.

Noriega was a military officer later turned politician, who became the de facto ruler of Panama during the period 1983–89. He was Torrijos’s head of intelligence and maintained long-standing ties with the CIA. Though the US backed Noriega as a valued friend, they had no illusions about him. In Washington circles, he was described as a ‘second-rate dictator and a third-rate drug trafficker.’ The American intellectual, Noam Chomsky, wrote of Noriega: ‘Noriega was involved in drug-trafficking since at least 1972, when the Nixon administration considered assassinating him. But he stayed on the CIA payroll. In 1986, the Director of the DEA (Drug Enforcement Administration) praised Noriega for his “vigorous anti-drug trafficking policy” and “welcomed our close association with him.” He served US interests satisfactorily but a brutal tyrant crosses the line from “admirable friend” to “villain and scum” when he commits the crime of showing independence. “Since we could no longer trust Noriega to do our bidding, he had to go. Actions we’d formerly condoned became crimes.” The demonisation of Noriega was a replay of the demonisation of Gaddafi in Libya. After the US invasion of Panama, Noriega was sentenced to 40 years imprisonment and died of complications from surgery for a brain tumour in 2017. The fact that he had been presented with the highest US military award by President Reagan during a visit to Washington in 1986 has been conveniently brushed under the carpet.

By 1985, Noriega was the de facto ruler of Panama and I, as part of his entourage, had joined the elite club. Our client list grew to include the rich and the powerful. In 1985, a charismatic young politician, Alan Garcia, was elected President of Peru. Known as the Kennedy of Latin America, he was anti-imperialist, populist, and a fiery orator. He moved to nationalise banks and insurance companies and limited repayment of Peru’s national debt. Washington was not amused. I met Garcia on many occasions and to me he was oddly reminiscent of Bhutto.

Noriega warned Garcia that Peru’s reserves were vulnerable if America chose to move against him and sent me to offer him banking assistance. In this way, Garcia was introduced to BCCI. Every banker dreams of the big client, the big deposit account. In Peru, I hit the jackpot. Garcia moved his country’s reserves to our bank and I secured my biggest deposit account, four billion dollars. BCCI started acting as the virtual central bank of Peru. Our bank prospered but the Peruvian economy suffered as hyperinflation reached astronomical heights by 1990. In 1990, Garcia was ousted from power by a coup. Army tanks took control of the area where he lived, but he managed to escape to a construction site where he hid until he found refuge in the Colombian embassy; he was given asylum by Colombia and extracted in a Colombian Air Force jet. Many years later, in 2006, he returned to Peru and won a second term as President. This time he had learned his lesson and his economy was a roaring success, surpassing even China in GDP growth and reducing poverty from 48 per cent to 28 per cent. On April 17, 2019 he committed suicide with a bullet to the brain.

BCCI fortunes were at their peak. With 400 branches in 73 countries, $20 billion in assets, and 16,000 employees, BCCI was the seventh largest private bank in the world. In South America, the opulent hotels and the parties of the sophisticated elite were our playground. One of our clients owned the Hilton hotel; when he defaulted in the repayment of his debt, we foreclosed on his magnificent mansion and his super luxury yacht. Abedi decided not to sell the yacht and we used it for entertainment of our VIP clients. Noriega loved the yacht and asked the bank to sell it to him. Abedi refused to sell but said Noriega could use it as his own for as long as he wished. The yacht was the scene of fabulous parties and exciting guests.

While we were enjoying success and the good life, the US was preparing its attack, on us, on the bank, on Noriega, on Panama, and on Garcia. Between 1986 and 1988, the US government set up an 11-agency task force to prepare its undercover sting operation C-Chase against BCCI. Robert Mazur, the lead agent, wrote a highly dramatised and self-serving book, which was later made into a film, The Infiltrator. After a two-year preparation, on October 8, 1988 a staged wedding was organised at a golf resort in Tarpon Springs, Florida. After the staged wedding, we were told that a stag party had been arranged at a private club in nearby Tampa. When the elevator reached the penthouse floor, we were thrown to the ground, handcuffed and separated for interrogation. The charges were conspiracy, drug-smuggling and money-laundering. The arresting officer put a gun to my head and shouted, “if you don’t cooperate, I will blow your brains out.” Dazed and disoriented, I didn’t know what I had to cooperate about. If cooperation meant implicating Noriega in drug-trafficking, I was dead anyway.

The operation was a set-up, the six-month trial a farce, the verdict a foregone conclusion. After paying $6 million to my lawyers alone, and similarly large amounts for my colleagues, the bank, concluding that there was no end and no upside to the proceedings, on the questionable advice of its US attorneys, pled guilty and sacked us all. I had to hire my own local lawyer to recover my car that had been confiscated; he won the case but took my beloved Mercedes 500S as I couldn’t pay his $80,000 fees. My beautiful Coral Gables house, the pride of my wife and myself, was also confiscated. I was sentenced to 12 ½ years’ imprisonment and fined $1 million.

A year after my arrest, US troops invaded Panama. 25,000 American soldiers attacked, killing thousands of locals, both military and civilian. Noriega took refuge in the Vatican Embassy but after 10 days, on January 3, 1990, surrendered to the US troops. Garcia was removed from the presidency in Peru and a year later, in 1991, BCCI was shut down in what the American press described as the “largest bank fraud in the world’s financial history.” In addition to the trumped-up charges of money-laundering, drug-trafficking, and conspiracy, the bank was also accused of financing the renowned terrorist Abu Nidal, laundering money for dictators such as Saddam Hussein, Manuel Noriega, Mohammad Ershad, and Samuel Doe. It was also alleged that the bank had helped in financing Pakistan’s nuclear programme. Mubashir Malik wrote in his book Double Standards – BCCI the Untold Story, that ‘The bank didn’t collapse. It was forcibly shut down. It was solvent at all times.’

The most blatant miscarriage of justice was the shut-down of BCCI by the Bank of England on grounds of capital inadequacy. The BCCI was given one week to increase its capital by half-a-billion dollars. Swaleh Naqvi, the CEO, was at a loss as to how to handle the crisis and flew in the BCCI corporate jet to Karachi to consult with Abedi, now retired and invalid after his heart transplant. When Naqvi explained his predicament, Abedi asked just one question, “Have you done anything that I would be ashamed of?” When Naqvi firmly stated that he had not, Abedi said I will handle the problem. Call Sheikh Zayed’s office and tell them that I am coming to meet him. The private jet was prepared and Swaleh Naqvi, Dildar Rizvi and Agha Hasan Abedi, in his wheelchair, left for Abu Dhabi.

They were settled into the Abu Dhabi Intercontinental, Abu Dhabi’s best hotel at the time, and Abedi was taken to meet Sheikh Zayed, the ruler of Abu Dhabi, and the main investor in the bank. Abedi told the Sheikh that he was dying and had come to say goodbye. He then told Zayed about the BCCI problem, that the bank needed half-a-billion dollars if it was to survive. Zayed told Abedi not to worry and that it would be taken care of. In a separate meeting between the bank’s executives and the managers of Sheikh Zayed’s funds, it was agreed that a billion dollars would be invested to establish adequate liquidity to satisfy the Bank of England. The money was sent, but the Bank of England nevertheless shut down the bank; capital inadequacy was just an excuse, the real reason was that the western powers had decided to kill BCCI.

The BCCI, Noriega, and Garcia were all gone. I was sentenced to 12 years and incarcerated in a prison in America. Even after my imprisonment, I was regularly interrogated about Noriega, about drugs, about Pakistan’s nuclear programme. Since I was uncooperative, I was moved from prison to prison — The Tombs, Ryker’s Island, Atlanta Penitentiary — altogether 23 prisons selected for distance and violence, the purpose being to make it so difficult for me that I would do their bidding. The most dangerous room in a prison was the TV room, with frequent stabbings using the shank, a homemade knife, in disputes over the choice of channel. I learnt to stay away from television, a habit I retain to this day.

Every prison has gangs, and to survive you had to be accepted by a gang who would protect you from random assault —the Bikers, the Mexican Mafia, the Bloods, the Crips, the Muslims. My safety lay with the Muslims. The most feared were the Italian Mafia, whose members appeared dignified and almost gentle; all the other prisoners and the guards gave them respect and kept their distance.

One day, a quiet, elegant inmate walked up to me and asked to play a game of Scrabble. We played, I won, and he became my regular scrabble partner. A few days later he managed my transfer to his cell where we spent the time playing scrabble and chatting through the long nights. He was Alphonse “Allie Boy” Persico, son of Carmine Persico, the crime boss of the New York Colombo family. In 1987, Carmine was sentenced to 139 years in prison, but continued to run his crime family from prison with multiple murders ordered from his cell. Al Persico was sentenced to life without parole. His wife had left him and was dating a man who was shot multiple times and killed, allegedly for his ill-advised romance with the wife of the new ‘Capo.’ My days with Al were comfortable, and his mafiosi made sure we were fed the best food I had ever eaten in prison.

Another inmate was the plump and friendly Armenian, Sarkis Soghanalian. He was polite to all, except for President Bush, whom he constantly cursed in the strongest language. Sarkis was an international arms dealer known around the world as ‘The Merchant of Death,’ who sold arms to all who could pay, without discrimination. In 1993, he was imprisoned for smuggling 103 helicopters to Iraq, but released early as he provided valuable deniability to the US government. After his incarceration he felt betrayed, most of all by Bush. He had a fleet of private aircraft, his favourite being a lavishly-equipped Boeing 707, luxury yachts and luxurious homes in a dozen countries. Presidents, Senators, royals and Hezbollah leaders counted him as a friend, and he spoke many languages.

Finally, after 7½ long and terrible years, I was released, transported to the airport in handcuffs and fetters, and deported to the UK. Was I finally free? At London, I disembarked and walked up to the immigration counter where I had spotted a kindly-looking, grey-haired lady officer. For a long five minutes she studied my British citizenship papers as I stood before her, anxious about my future. She then looked up at me, smiled, and said, “Welcome home, Sir.”

The writer is a businessman and the author of three books including Muslims: The Real History.