The world economy was already witnessing a synchronised downturn even before the outbreak of COVID-19. The outbreak has simply dealt a major blow to the $133 trillion world economy by totally devastating it with a speed which has not been experienced in nearly a century. The leading economies of the world have witnessed massive contraction, throwing many millions out of work and into poverty and hence, wiping out the gains of the last several decades that took millions out of poverty. Like the major economies, the pandemic has also severely damaged the economies of the developing countries, including the economies of low-income countries (LICs).

The pandemic has triggered unprecedented policy responses around the world. Governments in both developed and developing countries have taken extraordinary measures to prevent the spread of the virus. At the back of collapsing private sector demand, governments around the world used both fiscal and monetary stimulus to prop up aggregate demand and accordingly accumulated unprecedented debts. While developed economies have enormous capacity to afford high debt burdens, it is the developing countries and particularly the LICs that now face a rising debt burden. Most importantly, the LICs face the risk of catastrophic sovereign debt crisis with a possibility of disorderly debt default. Pakistan, being a low-income country, has also witnessed its economy contracting, revenue efforts faltering, expenditure on social protection — COVID-19-related and for the economic revival — elevating, budget deficit ballooning and both public and external debts reaching unsustainable levels.

It is important to note that the debt level of the LICs were already high and unsustainable even before the onset of COVID-19. According to an IMF study published in February 2020, half of the LICs, that is, 36 out of 76 countries, were at high risk of or already in debt distress. At the same time, sovereign debt downgrades by the major international credit rating agencies have soared in 2020 — to the highest level in 40 years. Argentina, Ecuador, Lebanon, Suriname and Zambia have already defaulted on their external debt payment and are at various stages of the debt restructuring process.

At the back of collapsing private sector demand, governments around the world accumulated unprecedented debts. Many LICs face the risk of catastrophic sovereign debt crisis with a possibility of disorderly debt default.

The total external debt stock of the LICs eligible for the debt relief provided by the G-20 countries stood at $744 billion in 2019, equivalent to, on average, 33 percent of their Gross National Income (GNI). Total debt owed to private creditors amounted to $102 billion and to official bilateral creditors, composed mainly of G-20 countries, at $178 billion at the end of 2019. Such a high level of debt overhang is likely to slow investment and growth for years to come in the LICs. COVID-19 has pushed the debt level of these countries to a new height because of pandemic-related expenditures; their revenues faltered because of the contraction of their economic activities, resulting in a rising budget deficit and accordingly a rise in debt. As a result, the pandemic has adversely affected both the solvency and liquidity indicators of these countries. The extent of debt distress of these countries will depend on the depth and duration of the pandemic’s impact. Given the emerging post-pandemic debt situation in developing countries in general and the LICs in particular, it is highly likely that the world may witness a repeat of the disorderly defaults of the 1980s.

Pakistan’s external debt and liabilities (EDL) were growing at an alarming pace even before the onslaught of Covid-19. Major factors that contributed to the surge in debt included fiscal profligacy, stagnant or declining exports, sharp depreciation of the exchange rate, keeping the discount/policy rate at an elevated level, borrowing in foreign currency to build foreign exchange reserves, and a decline in non-debt creating inflows.

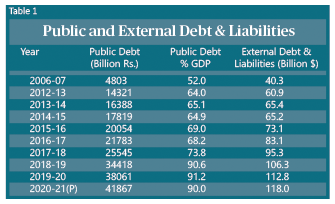

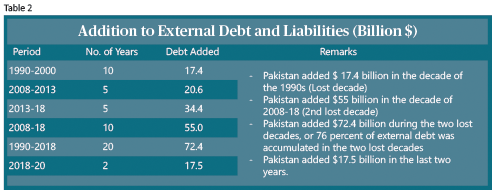

COVID-19 has further aggravated the country’s debt situation. Pakistan’s external debt and liabilities stood at $40.3 billion in end-June 2007, and increased to $95.3 billion in 2017-18 — an increase of $55 billion in one decade or $458 million per month (See Table 1). It has further increased to $113.8 billion by September 2020 — that is, an addition of $18.5 billion in 27 months or $685 million per month. It is important to note that Pakistan added $72.4 billion during the two lost decades or 76 percent or over 3/4th of its EDL were accumulated in the two lost decades (See decade of the 1990s and the decade of 2008-18). The pace of debt accumulation over the last two and a quarter years is ominous (see Table 2). It is interesting to note that one thing was common in the two lost decades in which the country accumulated more than 3/4th of its EDL, that is, Pakistan remained in the IMF programme. Pakistan is again in the IMF programme and the debt is accumulating rapidly. Pakistan’s EDL is projected to rise to $118 billion and public debt to Rs. 41867 billion (or 90 percent of GDP).

Against this deteriorating debt situation that COVID-19 struck Pakistan, creating a perfect storm for public finances. On the one hand it hit tax collection and on the other resulted in a sharp increase in pandemic-related expenditure, putting tremendous strain on government. Notwithstanding the perfect storm, Pakistan like many other countries around the world, undertook expansionary fiscal and monetary policies to protect the vulnerable sections of society; to prevent job losses, bankruptcies and revive the economy. While Covid-related expenditure surged, the tax efforts of the government faltered equally, causing the budget deficit to remain at an elevated level, causing public debt to increase sharply. Like other LICs, Pakistan also faced serious difficulties in honouring its debt service obligations in an orderly manner because of declining exports and other non-debt creating inflows. With increased debt vulnerabilities, fiscal pressures, and a global economic meltdown, Pakistan’s capacity to absorb more debt has been weakened. Pakistan faced a serious dilemma in choosing between servicing debts to the lender and helping the vulnerable sections of society, including workers, small shopkeepers and so on. There is now a growing consensus at the global level regarding the likelihood of a protracted debt crisis in developing countries in general and LICs in particular.

Debt Relief

COVID-19 has severely damaged the economies of both rich and poor countries, more so of the LICs, hampering their debt repayment capacity. Therefore, multi-lateral institutions like the World Bank, the IMF and the G-20 countries moved forward to assist the LICs by alleviating their immediate liquidity needs. At the request of the leadership of the two multilateral institutions, the G-20 countries announced in mid-April 2020 a debt payment freeze for 77 IDA eligible countries (mostly from Africa) including Pakistan. Under the Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI), debt service payments (both principal and interest) to the official bilateral creditors of the 77 eligible countries were suspended for the period May 1 to December 31, 2020. Private creditors were simply asked to participate in this initiative on a voluntary basis. If all the eligible (77) countries participated in the DSSI, it would have freed up about $12 billion. According to the initiative, debt payment of eligible countries due during the period May 1 to December 31, 2020 was to be suspended and will be paid back in three years with a one year grace period.

The DSSI received a lukewarm response from the eligible countries, as only 46 out of 77 countries (60 percent) applied and succeeded in deferring $5.7 billion in debt service payments. Why did the DSSI attract only 60 percent of the eligible countries? There are several reasons for the lukewarm response. Firstly, the structure of the debt of eligible African countries suggests that out of the $405 billion total debt, only 20 percent ($81 billion) is owed to official bilateral creditors whose debt service payments were supposed to be suspended. Out of the total debt, 32 percent or $132 billion is owed to private creditors and bond markets and 35 percent or $144 billion is owed to multilateral institutions such as the World Bank and the IMF, with the remaining 12 percent or $48 billion owed to various other lending agencies. Thus, this initiative, according to the eligible countries, excluded multilaterals, bond holders, private creditors, and others accounting for 80 percent of the total debt or $324 billion. Therefore, 40 percent of the eligible countries did not participate in the initiative.

The G-20 debt relief is a temporary respite and not “relief” or forgiveness

Secondly, the DSSI barred the eligible countries from raising resources from the international debt capital market. The rating agencies had clearly warned that if the eligible countries insisted on freezing debt payments to private creditors (bond holders), this would be treated as sovereign default and as such would attract immediate downgrading. The eligible countries did not want to sever their relations with the debt capital markets.

Thirdly, from the viewpoint of the eligible countries, the G-20 debt relief is a temporary respite and not “relief” or forgiveness. Whatever “relief” they receive from the G-20 today will be fully repaid with additional interest to compensate for the delay in payment, because this initiative is neutral in effect or in Net Present Value (NPV) terms. The risk of disorderly default is rising. Some economists believe that these eligible countries were already in debt distress and with this debt relief, debt default has been merely postponed for a few years and disorderly default is inevitable.

Fourthly, there is a condition in this initiative that the countries seeking debt relief should either already be in an IMF programme or in negotiations for such a programme. Many LICs do not want to implement a four decades old stabilisation programme. Hence, those 40 percent eligible countries did not apply for debt relief to avoid being under the IMF programme. Since Pakistan is already implementing an IMF programme, it decided to apply for the debt relief.

Taking advantage of the DSSI, Pakistan also applied to join the debt standstill initiative and secured a relief of $1.7 billion. In other words, debt payment which was due during the period May 1 to December 31, 2020 amounted to $1.7 billion. Pakistan will not be paying this amount and hence it was a saving made possible through the DSSI. This relief was in fact a postponement of the debt payment and not the forgiveness of debt service. Pakistan will have to repay $1.7 billion in the next few years with additional interest. Apart from the temporary debt relief, Pakistan also received $1.4 billion under the IMF’s Rapid Financing Initiative to alleviate its liquidity concerns. The World Bank, the Asian Development Bank and Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank have fast-tracked their lending amounting to $1.6 billion for the same purpose.

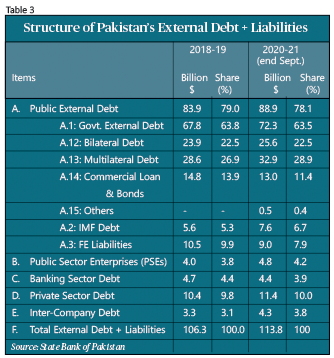

Like the debt structure of eligible African countries, where bilateral official creditors accounted for only 20 percent of their total debt, in Pakistan too, the structure of the debt is such that only 22.5 percent or $25.6 billion external debt is owed to bilaterals while $63 billion or over 55 percent is owed to multilaterals, the IMF, commercial banks, bond holders and others (See Table 3). Accordingly, Pakistan also benefited very little from the DSSI.

Carmen Reinhart, Kenneth Rogoff, and their co-authors have recently published an article in the September 2020 issue of Finance and Development — a quarterly publication of the IMF — in which they have argued that multilateral institutions like the IMF and the World Bank have generously offered loans to developing countries in general and LICs in particular, and the G-20 offered debt payment postponement. All these loans were offered to meet pandemic–related expenditures. In the process, these institutions and the G-20 have further burdened the recipient poor countries with more debt and simply extended the list of countries in debt distress and, accordingly, sowed the seeds for a full-blown debt crisis.

Notwithstanding the above facts, the G-20 debt relief was an excellent first step in the right direction. It provided temporary relief to the LICs including Pakistan, enhanced their fiscal space which enabled them to spend on social protection, reviving economic activities and to meet Covid-related expenditures. The pandemic has caused unparalleled devastation to the global economy in general and to the economies of developing and LICs in particular. There is a consensus among the economists that it will take a minimum of two to three years for these economies to come back to the pre-Covid level. Realising this fact, the G-20 countries have extended the debt relief to June 2021 and the repayment period has been extended to six years. There are indications that this relief can further be extended to December 2021 with a decision to be taken during the IMF-World Bank meeting in April 2021.

Eurodad, a network of 50 European NGOs specialising in poverty reduction, has argued that the DSSI package does not go far enough and has warned that the low-income countries would face a debt repayment crisis from 2022 onwards.

How much additional benefits will accrue to the LICs, including Pakistan, due to the extension of the debt standstill for six months (June 2021)? Estimates suggest that all the 46 countries that have already signed the DSSI will initially receive further relief of $6.4 billion. Estimates also suggest that Pakistan will receive additional benefits in the range of $800-900 million. The total relief for Pakistan would be $2.5-2.6 billion for the period May 1, 2020 to June 30, 2021.

Eurodad, a network of 50 European NGOs specialising in poverty reduction, has argued that the DSSI package does not go far enough and has warned that the low-income countries would face a debt repayment crisis from 2022 onwards. They have also stated the DSSI eligible countries will be paying over $9.0 billion to multilateral banks, of which, more than $2.0 billion has been paid to the World Bank alone during the May–December 2020 freeze period. The World Bank has so far received as much in debt service payments as it has given out in Covid-related grants. In other words, the debt relief provided by the official bilateral creditors has gone back to multilateral institutions like the World Bank. This is one of the reasons that the DSSI received a lukewarm response from the eligible countries. Even the extension of debt relief to June 2021 may not attract more eligible countries.

Comprehensive Debt Relief Initiative (CDRI)

According to Carmen Reinhart, Kenneth Rogoff and their co-authors, COVID-19 is a once-in-a-century shock that merits a generous response from all the stakeholders — official bilateral creditors, multilateral institutions, and private creditors. While rich economies will emerge out of the crisis soon, LICs, already in debt distress conditions, may take a much longer time to revive their economies because of their debt overhang. If the international community does not provide generous support at this juncture of economic history, there is a danger that the developing countries as a whole may see a protracted debt crisis. A full debt standstill is an absolute necessity to prevent a full-blown debt crisis. It does not make sense that the relief provided by the official bilateral creditors is siphoned off by multilaterals and private creditors.

Under the evolving deteriorating debt situation, everyone (bilaterals, multilaterals and private creditors) will have to share the burden. Firstly, the debt standstill period should be extended for another three years at least — up to December 2023. Let the bilaterals suspend their debt repayment for another three years. Secondly, the multilaterals — knowing that they are preferred creditors, and their debts are neither forgiven nor suspended — will have to come forward and share a proportionate burden. They are preferred creditors in normal times, but these are abnormal times that require out-of-the-box solutions. The multilateral debt is far larger than the bilateral one. Their participation in the debt standstill initiative will go a long way in addressing the serious debt situation. Let the debt repayment of multilateral institutions be suspended till December 31, 2023. This will give breathing space to eligible countries to fix their economies and bring debt situation under control.

Like the LICs, Pakistan also saw its EDL grow during the decade of 2008-18 at a speed not witnessed before

Thirdly, the most difficult and challenging part of the CDRI is to convince private creditors to suspend debt repayment. It is suggested that the private creditors may extend the life of the bond repayment. For example, if the eligible country has floated a sovereign bond in the international debt capital market for a 5-year tenure amounting to $1.0 billion and the payment schedule is prepared in such a way that the principal and the interest are to be paid back to the bond holders in 5 years’ time, it is proposed that this payment schedule be extended to 10 years. This would reduce the debt repayment burden of the eligible countries to half. In other words, the bond holders will continue to receive their payments according to the schedule, but the payments will be one half because the maturity of the bond has been extended to 10 years. In my opinion, this is a compromise solution to invite private creditors to join the CDRI.

Indeed, COVID-19 has caused unprecedented damage to the global economy. The debt of the LICs had already reached unsustainable levels even prior to COVID-19. It has now further been aggravated. If no concrete action or out-of-the-box solutions are found, the world may witness disorderly debt defaults in LICs. Like the LICs, Pakistan also saw its EDL grow during the decade of 2008-18 at a speed not witnessed before. Such a threatening pace has continued over the last two and a quarter years. The G-20 debt relief is a great step in the right direction, but it has only covered the official bilateral creditors. Given the scale of damage, it is proposed that the international community should consider comprehensive debt relief including all the stakeholders, that is, official bilateral creditors, multilaterals, and private creditors.