America pulls out of its longest-ever military engagement without losing the war — but without winning it either.

Two decades ago, President George Bush had announced the beginning of the Afghan war, declaring: “Initially, the terrorists may burrow deeper into caves and other entrenched hiding places. Our military action is also designed to clear the way for sustained, comprehensive and relentless operations to drive them out and bring them to justice.”

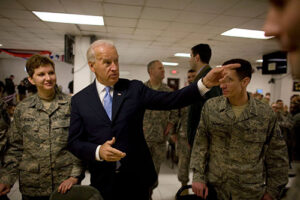

20 years later, President Joe Biden gave the US military a deadline: the withdrawal of all remaining troops in Afghanistan by the upcoming twentieth anniversary of the 9/11 attacks. “It’s time to end the Forever War,” he said.

In the almost two decades since America went to war in Afghanistan, it never provided a plausible explanation of its goals and how it planned to achieve them.

Afghanistan, a land of breathtaking beauty, torn by religious, ethnic and tribal divisions, has been at the centre of geopolitical contests for centuries. Despite the not-so-distant Soviet experience, American officials and generals never absorbed one simple fact: you can’t fight ghostly warriors who disappear into the mountains.

As the Americans sought revenge for 9/11, what sentiment did they evoke in those who watched daisy-cutter bombs rain hellfire? Or saw a wedding party disintegrate in a flash from an American airstrike? How many enemies did they spawn in the process of “trying to help” Afghanistan? Taliban leaders have famously said, “Americans have all the clocks, but we have all the time.”

The US military, with British support, began a bombing campaign against Taliban forces, officially launching Operation Enduring Freedom on October 7, 2001. The war’s early phase mainly involved US airstrikes on al-Qaeda and Taliban forces. The conventional ground forces arrived twelve days later. Most of the ground combat was between the Taliban and its Afghan opponents.

After losing Mazar-e-Sharif on November 9, 2001, the Taliban regime unravelled, ceding power to forces loyal to Abdul Rashid Dostum, an ethnic Uzbek military leader. Over the next week, after coalition and Northern Alliance offensives on Taloqan, Bamiyan, Herat, Kabul, and Jalalabad. Taliban strongholds crumbled one after another. The same day, the UN Security Council passed Resolution 1378. The resolution called for a “central role” for the United Nations to establish a transitional administration and invite member states to send peacekeeping forces to promote stability and aid delivery.

After the fall of Kabul in November 2001, the United Nations invited significant Afghan stakeholders to a conference in Bonn, Germany. On December 5, 2001, the factions signed the Bonn Agreement, endorsed by UN Security Council Resolution 1383. Iranian diplomatic support sealed the agreement. And because Iran supported the Northern Alliance faction, Hamid Karzai was installed as interim administration head, and an international peacekeeping force was created to maintain security in Kabul. The Bonn Agreement was followed by UN Security Council Resolution 1386, which established the International Security Assistance Force, or ISAF.

At the Bonn Conference, reconstruction emerged as a poorly articulated subsidiary goal of broad strategic priorities. The stated “strategy” has considerably changed over the past two decades, coloured by fluctuating funding allocations, the lack of a skilled civilian expeditionary corps, and domestic politics in the US and Europe.

The Western media declared the end of the Taliban regime after the Taliban surrendered Kandahar and Mullah Omar fled the city, leaving it under tribal law administered by Pashtun leaders. Despite the official fall of the Taliban, however, al-Qaeda leaders continued to hide out in the mountains.

Operation Anaconda, the first significant ground assault, was launched against an estimated eight hundred fighters in the Shahi-Kot Valley south of Gardez (Paktia Province) in March 2002. Nearly two thousand US and one thousand Afghan troops battled the militants. Despite the operation’s size, however, Anaconda did not represent a broadening of the war effort. Instead, Pentagon planners began shifting military and intelligence resources in the direction of Iraq.

Hamid Karzai, chairman of Afghanistan’s interim administration since December 2001, was picked to head the country’s transitional government. His selection came during an emergency Loya jirga assembled in Kabul, attended by 1,550 delegates (including about 200 women) from Afghanistan’s 364 districts. Karzai, leader of the powerful Popalzai tribe of Durrani Pashtuns, returned to Afghanistan from Pakistan after the 9/11 attacks to organise Pashtun resistance to the Taliban. Some observers alleged Karzai tolerated — and continues to tolerate — corruption by members of his clan and his government. The Northern Alliance, dominated by ethnic Tajiks, failed to set up a prime ministership but did succeed in checking presidential powers by assigning foremost authorities to the elected parliament, such as the power to veto senior official nominees and to impeach a president.

By the end of 2002, the U.S. military created a civil affairs framework to coordinate redevelopment with UN and non-governmental organisations and expand the Kabul government’s authority. While credited with improving security for aid agencies, the model was not universally praised. Criticism grew beyond the PRT (Provincial Reconstruction Team) programme and became a common theme in the NATO (North Atlantic Treaty Organization) war effort. In December 2002, delegates of the Constitutional Loya Jirga debated whether Afghanistan should have a robust presidential government or become a parliamentary democracy.

By August 2003, NATO assumed control and expanded NATO/ISAF’s role across Afghanistan. It was NATO’s first operational commitment outside Europe. Initially tasked with securing Kabul and its surrounding areas, NATO expanded in September 2005, July 2006, and October 2006. The number of ISAF troops grew accordingly, from an initial five thousand to around sixty-five thousand troops from forty-two countries, including all twenty-eight NATO member states. In 2006, ISAF assumed command of the international military forces in eastern Afghanistan from the US-led coalition and became more involved in intensive combat operations in southern Afghanistan.

Violence increased across the country during the summer months of 2006. The number of suicide attacks quintupled from 27 in 2005 to 139 in 2006, while remotely detonated bombings more than doubled, to 1,677. Despite a string of election successes, some experts blamed a faltering central government for the spike in attacks.

Cracks started to appear in the coalition by November 2006. At the NATO summit in Riga, rifts emerged among member states on troop commitments to Afghanistan. NATO Secretary-General Jaap de Hoop Scheffer set a target of 2008 for the Afghan National Army to begin to take control of security. Leaders of the twenty-six countries agreed to remove some national restrictions. But friction continued. With violence against non-governmental aid workers increasing, US Secretary of Defence Robert Gates criticised NATO countries in late 2007 for not sending more soldiers.

By August 2008, “collateral killings” reached their peak. Afghan and UN investigations found that a US gunship killed dozens of Afghan civilians in the Shindand District of western Herat Province. The incident drew condemnation from President Hamid Karzai. After being named top US commander in Afghanistan in mid-2009, Gen. Stanley A. McChrystal ordered an overhaul of US airstrike procedures. “We must avoid the trap of winning tactical victories, but suffering strategic defeats, by causing civilian casualties or excessive damage and thus alienating the people,” the general wrote.

Newly elected US President Barack Obama announced plans to send seventeen thousand more troops to Afghanistan soon after taking office. He said the United States would stick to a timetable to draw down most combat forces from Iraq by the end of 2011. The defining mistake of Obama’s first-term foreign policy was his decision to escalate American military operations in Afghanistan. There were 35,000 American troops in Afghanistan when Obama was inaugurated. By the summer of 2011, there were roughly 100,000.

Senior US military officials and commanders, altering course from the Bush administration, called on NATO nations to supply non-military assets to Afghanistan. Secretary of Defence Robert Gates replaced the top US commander in Afghanistan, Gen. David D. McKiernan, with counterinsurgency and special operations guru Gen. Stanley A. McChrystal. Gates said the Pentagon needed “fresh thinking” and “fresh eyes” on the Afghanistan war when operations there were spiralling out of control. With new leadership in place, US Marines launched a major offensive in southern Afghanistan, a test for the US military’s new counterinsurgency strategy. The offensive, which involved four thousand Marines, was launched in response to a growing Taliban insurgency in the country’s southern provinces, especially Helmand Province.

After more than two months of uncertainty following a disputed presidential election, President Hamid Karzai won another term. The election, which pitted Karzai against top contenders Abdullah Abdullah and Ashraf Ghani, was marred by fraud allegations. An investigation by the UN-backed Electoral Complaints Commission found Karzai had won only 49.67 per cent of the vote, below the 50 per cent-plus-one threshold needed to avoid a runoff. Under international pressure, Karzai agreed to a runoff vote. But a week before the runoff, Karzai’s main rival Abdullah pulled out of the race, and Karzai was declared the winner. Concerns over Karzai’s legitimacy grew, and the United States and other international partners called for improved governance. US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton tied all future civilian aid to greater efforts by the Karzai administration to combat corruption.

Nine months after renewing the US commitment to the Afghan war effort, President Obama announced a significant escalation of the US mission. These forces, Obama said, “will increase our ability to train competent Afghan Security Forces and to partner with them so that more Afghans can get into the fight. And they will help create the conditions for the United States to transfer responsibility to the Afghans.”

For the first time in the eight-year war effort, a time frame was put on the US military presence, as Obama declared the start of a troop drawdown by the summer of 2011. But the president did not detail how long a drawdown would take.

At a summit in Lisbon, NATO member countries signed a declaration agreeing to hand over full responsibility for security in Afghanistan to Afghan forces by the end of 2014. The transition process began in July 2011, with local security forces taking over control in relatively stable provinces and cities. The initial handover was to coincide with the start of a drawdown in the one hundred thousand contingents of US troops deployed in Afghanistan.

On May 1, 2011, al-Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden, responsible for the 9/11 attacks in New York and Washington, was killed by US forces in Pakistan. The death of America’s primary target for a war that started ten years ago fuelled the long-simmering debate about continuing the Afghanistan war. As President Obama prepared to announce the withdrawal of some or all of the thirty thousand surge troops in July, congressional lawmakers increasingly called for a hastened drawdown of US troops.

Meanwhile, anti-Pakistan rhetoric grew in Afghanistan, where officials had long accused Pakistan of violence in Afghanistan. Afghan President Hamid Karzai claimed that international forces should focus their military efforts across the border in Pakistan. “For years, we have said that the fight against terrorism is not in Afghan villages and houses,” he said.

On June 22, 2011, President Obama outlined a plan to withdraw thirty-three thousand troops by the summer of 2012 —the surge troops sent in December 2009 —including ten thousand by the end of 2011.

Polls showed a record number of Americans did not support the war, and Obama faced pressure from lawmakers, particularly Democrats, to reduce US forces in Afghanistan sizably. After the surge troops left, an estimated seventy thousand US troops stayed through at least 2014.

Obama confirmed that the US was holding preliminary peace talks with the Taliban leadership. With reconciliation in mind, the UN Security Council days earlier split a sanctions list between members of al-Qaeda and the Taliban, making it easier to add and remove people and entities.

The US war in Afghanistan marked its tenth anniversary with a hundred thousand US troops deployed in a counterinsurgency role. Amid a resilient insurgency, the US goal in Afghanistan remained uncertain. The cost of war eroded US public support, already having to contend with a global economic downturn, a 9.1 per cent unemployment rate, and a $1.3 trillion annual budget deficit. While there were military gains, hope for a deal with the Taliban to help wind down the conflict remained riddled with setbacks.

Ten years after the first international conference that discussed Afghanistan’s political future, dozens of countries and organizations met again in Bonn, Germany. Afghan President Hamid Karzai said the government would require $10 billion annually over the next decade to shore up security and reconstruction. The conference failed to achieve its objectives — to lay down a blueprint for Afghanistan’s transition to a self-sufficient and secure government — as the insurgency continued.

By June 2013 the Afghan security takeover was announced: “completed.”

Afghan forces took the lead in security responsibility nationwide as NATO handed over control of the remaining ninety-five districts.

The handover occurred on the same day as the announcement that Taliban and US officials would resume talks in Doha, Qatar, where the Taliban had just opened an office. President Hamid Karzai, believing the office would confer legitimacy on the insurgent group and serve as a diplomatic outpost, suspended negotiations with the United States. With its mandate expiring in December 2014, the United States had to negotiate a bilateral security agreement with the Karzai government to maintain a military presence.

On May 27, 2014, President Barack Obama announced a timetable for withdrawing most US forces from Afghanistan by 2016. The first phase of his plan, which called for 9,800 U.S. troops to remain after the combat mission, concluded at the end of 2014, limited to training Afghan forces and conducting operations against “the remnants of al-Qaeda.” Obama said the drawdown would free resources for counterterrorism priorities elsewhere. Candidates vying to succeed President Hamid Karzai promised to sign the security agreement that was a prerequisite of any post-2014 US troop presence.

The newly elected president signed a power-sharing agreement with his chief opponent, Abdullah Abdullah. The deal was brokered on September 21, 2014. After intensive diplomacy by US Secretary of State John Kerry, the role of chief executive officer was established for Abdullah. The agreement ushered in protracted government dysfunction. Ghani and Abdullah tussled over their respective prerogatives, such as appointments to security posts, when the Taliban made gains in the countryside. Ghani, a former World Bank specialist, a Pashtun from the country’s south, like Karzai, but was seen by the Obama administration as a welcome change. Karzai had railed against civilian casualties in the US war effort and was seen as fostering public corruption.

The United States dropped its most powerful non-nuclear bomb in eastern Nangarhar Province on April 13, 2017. The “mother of all bombs” descended as newly elected President Donald Trump delegated decision-making authorities to commanders, including the possibility of adding several thousand US troops to the nearly nine thousand already deployed there.

A war-torn Afghanistan has negatively impacted Pakistan’s progress — a profusion of weapons and drugs and the presence of over two million Afghan refugees. A volatile Afghanistan has also undermined Pakistan’s objective of creating regional connectivity with Central Asia and emerging as a hub for intra-regional cooperation. For all these reasons, peace and stability in Afghanistan are in Pakistan’s strategic interest.

Recognising that there can be no military solution, Pakistan has consistently advocated a negotiated settlement. Pakistan facilitated US-Taliban talks and fully endorsed the US-Taliban deal and the start of the Afghan peace process. To help the process forward, it has repeatedly engaged with the US, Taliban and the Afghan government, advocating compromise and accommodation by all sides.

Two years later, the US and the Taliban signed the deal. US envoy Khalilzad and the Taliban’s Baradar signed an agreement that paved the way for a significant drawdown of US troops.

Twenty years later, President Biden committed a complete withdrawal by September 11, 2021. “It’s time to end America’s longest war,” he said.

Soon after Biden’s announcement, both Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell and the Republican senator Lindsey Graham and a few Democrats criticised the move. McConnell called “precipitously withdrawing” American forces from Afghanistan “a grave mistake.” Whatever one may think of Biden’s decision, after twenty years, it is certainly not precipitous.

We cannot ignore the sagacity of Sun Tzu, who said “as water retains no constant shape, so in warfare, there are no permanent conditions.”

Editor, Narratives