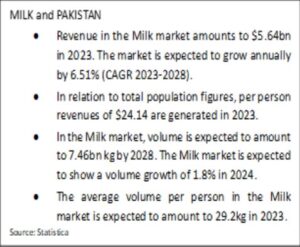

The dairy sector stands as a pivotal sub-sector within Pakistan’s agriculture, constituting a substantial 60.6% of the value-added agricultural segment and contributing significantly to the nation’s GDP at 11.7%. Notably, Pakistan holds the esteemed rank of the fourth-largest dairy producer globally, as recognized by the FAO. In the local context, an overwhelming 97% of milk consumption occurs in its unprocessed, fresh state, with only a modest 3% being processed, often as UHT milk.

The dairy farming landscape in Pakistan is characterized by smallholdings, predominantly engaging in subsistence or market-oriented farming. This is complemented by peri-urban and commercial-level dairy farming, reflecting the diversity of the sector’s operations. Small dairy farms around the world are grappling with an existential crisis. Dominant agribusinesses are aggressively consolidating their control over markets and policymaking, utilizing deceptive marketing tactics. These big dairy corporations have left smallholder dairy farms with two grim options: accumulate debt and expand, or face extinction. What began as a corporate takeover in the global north is now bulldozing its way through developing nations, sowing panic and misfortune among small farms.

In Pakistan, the stakes are exceptionally high. An astounding 80% of the country’s dairy production and distribution remains in the hands of small backyard farms and small-scale vendors. However, the public’s trust and reliance on the milk from these small-scale dairies are under constant assault by corporations and their allies in the government. They portray this milk as unsafe. A aspirations of the law makers are poised to ban the sale of fresh milk from small-scale dairies, granting corporations total control over the milk supply. This move places the livelihoods of millions of farmers and access to nutritious dairy for millions of poor consumers in grave jeopardy.

Livestock rearing and dairy farming form the backbone of Pakistan’s rural economy. Approximately 98% of Pakistan’s substantial peasant population is engaged in livestock farming, which is also a way of life. The animals they raise serve as a form of savings, to be sold in times of emergency or need. Over 8 million rural families are involved in dairy production, supporting approximately 35 to 40 million people. These families rely on dairy farming to meet their nutritional needs and supplement their income.

The milk from cows and buffaloes represents over a third of the average farming family’s revenue. Furthermore, the milk supplied by small farmers constitutes a source of income for thousands of small-scale vendors, known as “gwalas”. These vendors buy milk from dairy farmers and sell it directly to urban consumers or small-scale processors who transform it into cheese, yogurt, and other dairy products on a daily basis.

These smallholder dairies, comprised of small farmers with a few cattle or buffalo and small-scale vendors and processors, contribute more than 80% of the national milk supply. Big dairy corporations like Nestle, Friesland Campina, Engro, and Cargill make up a mere 5%, with the remaining 15% supplied by national commercial dairy companies such as Nishat, Dairyland, Friendship, Sharif, Sapphire, and Dada Dairies. To transnational dairy companies, Pakistan — the world’s 5th-largest milk producer — presents a massive potential market if they can seize it from the hands of small-scale dairies.

Corporations typically employ two tactics to wrest control of markets from small-scale dairies. One is to import inexpensive powdered milk from major surplus-producing countries in North America, Europe, and Oceania. The other is to lobby for laws and regulations that criminalize small-scale dairies. Large dairy companies have used these two tactics to dominate dairy markets across Asia and the world.

In Pakistan, corporations have had mixed success with the first tactic. When powdered milk imports soared to a record 44.2 million kilograms in 2015, almost exclusively from Europe, public pressure compelled the government to impose a 25% tariff on powdered milk imports. This was later raised to 45% in 2017 and then 60% in 2018, despite strong opposition from EU ambassadors and the big dairy lobby. Yet, even at these tariff levels, big dairy companies continue to import and undercut local farmers. During the COVID-19 crisis, farmers urged the government to ban powdered milk imports as they struggled with reduced demand and ongoing excessive imports. In this political context, corporate dairy companies had to rely heavily on the second tactic to overpower Pakistan’s small dairies.

For years, the big dairy companies have waged an unrelenting campaign in the media to vilify milk from small dairies. They label it as unhygienic, unsafe, adulterated, and of poor quality. Television advertisements depict gruesome images, attempting to draw consumers’ attention to the risks of consuming fresh milk, often referred to as “loose milk.” Despite their efforts to portray “gwalas” as malevolent culprits, most Pakistanis still prefer the untreated milk, which is readily available and less expensive than packaged milk.

Adulteration can indeed occur within small dairies. Milk delivery personnel may dilute fresh milk with water to increase its volume. During the hottest summer days, delivery personnel sometimes add ice to keep the milk cool and prevent spoilage during long trips. These practices are not new and have been occurring for centuries. They are not exclusive to small dairies, as large dairy companies face their own share of adulteration and contamination scandals.

Between 2007 and 2011, the Punjab Government — home to major dairy companies and the source of 73% of the country’s milk supply — enacted a Pure Food Law and a Food Safety Standards Act. These regulations, for the first time, introduced stringent penalties for milk adulteration. In 2016 and 2018, further regulations were done, banning fresh milk and mandating that all pasteurized milk must be sold in packaged form, labeled, and maintained at a specific temperature throughout the supply chain.

The new regulations of 2018 necessitate official registration of every farmer or cooperative engaged in milk production and sale, regardless of farm size or livestock numbers. These rules are practically impossible for smallholders to comply with. Authorities have, as a result, cracked down on small-scale dairies, leading to incidents where local officials have tried to expel dairy farmers with their cattle from city limits. Smallholder dairies, often surviving on the sale of fresh milk to urban populations, have faced significant challenges due to these regulations. In one instance, around 500 dairy farmers in Faisalabad were raided by municipal authorities in September 2019, forcing them to relocate. Only after the Lahore High Court intervened were these farmers allowed to temporarily remain within the city limits. The 500 dairy farming families in Faisalabad produce around 40,000 liters of fresh milk daily, most of which is consumed in the city, cutting into the profit margins of corporate dairies.

The pasteurization of milk became mandatory in Turkey in 1995, and in 2008, the sale of loose milk was banned. These moves aimed to bolster private and corporate sector milk production, resulting in a 90% increase in Turkey’s milk and milk by-product exports. This transition shifted the balance from small family enterprises with fewer than 20 herds to larger dairy farms.

Amid these corporate and regulatory challenges, the Pakistan Kissan Mazdoor Tahreek (PKMT), an alliance of small and landless farmers, has raised its voice against policies that undermine nutrition and employment for women and children. The PKMT has pointed out that the new policies will enable corporations to take over a dairy sector that has supported many women in feeding their families and earning an income. If smallholders are driven out of the dairy business, millions of families will not only lose a sustainable source of income but also a rich source of food and nutrition.

Despite these corporate actions, big dairy companies are still grappling with competition from smallholder dairies. FrieslandCampina, for instance, has yet to turn a profit after three years of substantial investments in Pakistan. While high taxes on their processed products are frequently cited as a justification for laws that criminalize smallholder dairies, these companies have now started to complain that these high taxes are causing consumers to prefer full-cream milk from smallholder dairies over their “safe” tea whiteners.

When corporations take control of a country’s dairy sector, they not only dominate the markets but also transform dairy farming practices. A shift occurs from small-scale, traditional agroecological methods to foreign industrial practices that require costly inputs and imported breeds.

To challenge the dominance of big dairy corporations, unorganized smallholder dairies must unite and defend their informal system and products, including fresh milk. These smallholders may follow traditional practices with minimal technology, but they effectively cater to the nutritional needs of a vast majority of Pakistan’s population. They also provide livelihoods and sustenance to around 40 million people directly or indirectly dependent on smallholder dairy farms.

Authorities in Pakistan, like in many other countries, are using food safety regulations not to protect consumers but to restructure the dairy sector in favor of corporations. Although, a capitalistic approach, this will not improve the milk supply for ordinary people, and it will seriously erode access to nutritious fresh milk, the variety favored by most Pakistanis. Rules and standards should support smallholder dairies, not undermine them. Governments have a crucial role in helping smallholder dairies improve the quality and safety of fresh milk in ways that are adapted to their realities. A complete ban on fresh milk will not only hurt farmers, but also affect everyone involved with smallholder farms, from shopkeepers and traders to delivery personnel, dealing a loss to the country that will only benefit the corporate sector.

The Battle of David and Goliath:

Large multinational companies are exploiting the milk industry by placing significant pressures on small farmers to increase the size of their holdings and improve breeding stock by moving towards improved (meaning imported) higher yielding cattle varieties. These operations, which may at first seem symbiotic, in connecting rural sellers to urban buyers, are in fact placing significant pressures on farmers to consolidate and finance their operations, options that are mostly available to richer and larger farmers.

The large commercial dairy marketers, in addition to their sale of packaged milk brands, are also at the forefront of promoting the sale of manufactured dairy products. Having these products in their portfolios allows them to target customers at lower price points which they’ve recognized as being potentially highly profitable since milk’s price (both fresh and packaged) continues to make it unaffordable for a large segment of the population. As per Nestle’s research, this group earns between $2-8 a day. We must recognize that it is precisely the practice of selling manufactured dairy products that undercuts the price of fresh, raw, and loose milk. This is because milk now has to compete against a product that can be manufactured at a lower cost, and to state the obvious is not milk but a substitute. It is this segment, fresh raw milk after all, that the companies see as their real competitor. (courtesy: Can Small Farmers Survive? Problems of Commercializing the Milk Value Chain in Pakistan)

The Government’s Role:

The government and the regulator have a significant role to play in the development and regulation of the dairy sector. Given Pakistan’s federal constitutional structure, agriculture, and thereby dairy, is a provincial subject with a potentially significant role for the provincial governments and NGOs within the context of the broader financing interface of the federal government with bilateral donors and international development finance institutions. The interplay of the two levels of government has a significant impact on developments on the ground in a given province, especially since agriculture is a residuary provincial power in the Constitution of Pakistan.

The government and the regulator can address the challenges faced by small dairy farmers by providing them with incentives and support beyond those operating on feed markets. They can also promote fresh, raw milk as a category and engage in testing and quality assurance checks at the points of collection to ensure the safety and quality of milk. The government can also provide small farmers with access to capital and financing to grow their farms to larger sizes, thereby improving their economic returns.

In addition, the government and the regulators can regulate the operations of large multinational and national dairy marketers to ensure that they do not exploit small farmers. They can also promote policies that protect small farmers from the pressures to consolidate and finance their operations, options that are mostly available to richer and larger farmers. The government can also promote policies that protect small farmers from the undercutting of the price of fresh, raw, and loose milk by manufactured dairy products.

How Big Dairy Companies Profit as Consumers Pay for Packaging

Dairy industry is a major player in Pakistan’s economy, providing livelihoods for millions and satisfying the nutritional needs of a vast population. Yet, a closer look at this industry reveals how big dairy companies extract value from fresh milk, often leaving consumers to bear the cost of packaging and distribution. If we explore this phenomenon, we can see how this dynamic unfolds in Pakistan’s unique context.

- Milk Procurement & Collection:

Big dairy companies in Pakistan maintain extensive networks for procuring and collecting fresh milk. They source milk from small dairy farmers, cooperatives, and individual suppliers. The aim is to secure a consistent supply of raw milk at the lowest possible cost. - Quality Control and Testing:

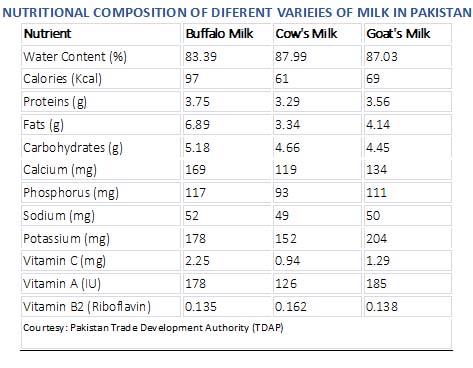

The collected milk undergoes rigorous quality control and testing procedures. Big dairy companies are committed to meeting specific quality standards and adhering to regulatory requirements. Testing includes parameters such as fat content, protein levels, temperature, and the absence of contaminants, ensuring both product quality and safety. - Processing and Value Addition:

After collection, the milk is transported to processing facilities where it is pasteurized or subjected to ultra-high-temperature (UHT) treatment to extend its shelf life. The value is added through various methods, including:

• Fortification: Essential vitamins and minerals are added to enhance the milk’s nutritional value, marketed as a health benefit.

• Flavoring: Flavors like chocolate or strawberry are introduced to cater to diverse consumer preferences.

• Dairy Product Production: Fresh milk is transformed into a variety of dairy products, such as cheese, yogurt, butter, ice cream, which often offer higher profit margins compared to raw milk.

• Packaging: The milk is packaged in different formats, from cartons and bottles to pouches and single-serve containers, creating opportunities for branding and marketing.

- Branding and Marketing:

Big dairy companies heavily invest in branding and marketing to position their products in the market. They emphasize quality, taste, health benefits, and convenience to build consumer trust and loyalty, which justifies premium pricing. - Distribution and Supply Chain Efficiency:

Efficient distribution networks are vital to ensure products reach retailers across the country. Big dairy companies excel in supply-chain management, optimizing transportation, warehousing, and distribution. This minimizes operational costs and ensures their products remain readily available. - Pricing Strategies:

Big dairy companies use diverse pricing strategies to maximize profits. These include competitive pricing to maintain market share, premium pricing for specialized or high-quality products, and promotional pricing to stimulate sales. - Consumer Pays for Packaging:

Consumers in Pakistan often pay for packaging through the price of dairy products. Packaging costs are typically included in the overall product price, meaning consumers pay more for packaging and distribution than the actual milk content. - Sustainability Initiatives:

In response to growing environmental concerns, some big dairy companies invest in sustainability initiatives to reduce their carbon footprint. While these initiatives aim to appeal to eco-conscious consumers, they can also serve as a marketing strategy to justify premium pricing. - Consumer Choice and Awareness:

In Pakistan, consumers have the power to influence the dairy industry. By making informed choices and supporting brands that prioritize quality and transparency, consumers can shape the practices of big dairy companies and advocate for more sustainable and cost-effective solutions. - Challenges and Opportunities:

Pakistan’s dairy industry faces challenges, including inefficient supply chains, milk adulteration issues, and limited access to formal markets for small dairy farmers. However, it also presents opportunities for innovation, sustainable practices, and consumer-driven change.

The dairy industry in Pakistan, much like elsewhere, witnesses big dairy companies adeptly extracting value from fresh milk while consumers unwittingly bear the brunt of packaging and distribution costs. To navigate this dynamic, consumers in Pakistan can educate themselves, make informed choices, and actively promote transparency and cost-effectiveness in the dairy sector. After all, consumers deserve both quality and value for their money in Pakistan’s diverse dairy landscape.

Challenges of Small Dairy Farmers in Pakistan:

According to an article in the Journal of Food Law & Policy, by Erum Sattar of the Tufts University, Boston, small dairy farmers face several challenges in commercializing their milk value chain in Pakistan. Some of these challenges include:

• Dependence on regular income: Farmers and tenant farmers get paid for their crops when they harvest and bring them to market. Thus, the farming calendar makes the regular weekly income farmers can get from the sale of milk necessary for them to be able to meet their household expenses. Landless livestock farmers are even more dependent on their earnings from the sale of milk.

• Pressure to consolidate: The structural transformation in the dairy sector that is underway in Pakistan, in which large companies move in to connect livestock and small farmers with urban consumers by being a source of regular income, is the very process through which the logic of the market may triumph at the cost of those same livestock, small farmers, and landless agricultural workers. Given the pressures on small farmers to consolidate, greater infusions of regular payments, which at first glance may seem to be what a resource-poor rural economy needs, is the very mechanism by which small farmers are made to feel the need to consolidate. Allowing them to feel the pressures through the transmission of price signals to overcome the small sizes of their landholdings and herds.

• Lack of capital and financing: Small farmers face the lack of capital and financing that they need to grow their farms to larger sizes, thereby improving their economic returns. The Kisan (farmer) Club subsidizes farm inputs, such as chillers, cow purchases, and breed improvement, through helping finance bank loans, or through innovative partnerships for digital micro-finance lending. However, the Milk Procurement and Marketing Companies (MPMC’s) have also put in place testing and quality assurance checks at the points of collection. They perform various qualitative and quantitative tests at the Village Milk Collection centers, as well as at their Regional Milk Collection centers.

• Inadequate animal nutrition: Inadequate feed leading to low dairy yields is a complex problem for the small farmers. The problem may be more complex than what some companies identify. On a major study mission of Pakistan’s dairy sector, Australian experts identified the problem of insufficient feed consumed by dairy animals, which is recognized by scientists, as is the fact that this is aggravated by continuous increases in the milking animal population. Farmers need to understand basic principles of animal nutrition, and there is a need for a dairy council or cooperative that would engage in promoting fresh, raw milk as a category.

The small dairy farmers in Pakistan face challenges such as dependence on regular income, pressure to consolidate, lack of capital and financing, and inadequate animal nutrition.

Creating a Win-Win-Win Market

To address the challenges faced by small dairy farmers in Pakistan, the solutions can be implemented from a more people centric policy paradigm that can create a win-win-win situation for the farmers, sellers, and the consumers:

- Incentives and support beyond feed markets: Small farmers need incentives and support beyond feed markets to improve their economic returns. The government needs to develop a mechanism to provide small farmers with access to capital and financing to grow their farms to larger sizes. The Kisan (farmer) Club can subsidize farm inputs, such as chillers, cow purchases, and breed improvement, through helping finance bank loans, or through innovative partnerships for digital micro-finance lending

- Promotion of fresh, raw milk as a category: The government needs to promote fresh, raw milk as a category and engage in testing and quality assurance checks at the points of collection to ensure the safety and quality of milk. The Milk Procurement and Marketing Companies (MPMC’s) can perform various qualitative and quantitative tests at the Village Milk Collection centers, as well as at their Regional Milk Collection centers. These include organoleptic, temperature, clot on boiling, fat%, solids not fat, total solids, and specific gravity. Tests for aflatoxins, antibiotics, and other contaminants are also performed. Separating the testing service from the collection service can create more transparency, employment opportunities and dilute the influence of the big dairy stakeholders.

- Regulation of large multinational and national dairy marketers: The governments should regulate the operations of large multinational and national dairy marketers to ensure that they do not exploit small farmers. Policies can be put in place to protect small farmers from the pressures to consolidate and finance their operations, options that are mostly available to richer and larger farmers. Policies can also be put in place to protect small farmers from the undercutting of the price of fresh, raw, and loose milk by manufactured dairy products.

- Consumer education: The government and dairy stakeholders can provide consumer education on the benefits and differentiation between the packaged and fresh, raw milk and the risks associated with consuming manufactured dairy products. This will enable consumers to make informed decisions about the milk they consume.

- Improvement of animal nutrition: Small farmers need to understand basic principles of animal nutrition. The government can provide training and education to small farmers on animal nutrition. A dairy council or cooperative can be established to engage in promoting fresh, raw milk as a category.

The future prospects and the challenges faced by small dairy farmers is to provide incentives and support beyond feed markets, promote fresh, raw milk as a category, regulate the operations of large multinational and national dairy marketers, and improve animal nutrition. These solutions can help small farmers improve their economic returns and ensure the safety and quality of milk.

Pakistan can draw several valuable lessons from Amul’s success story in India. Firstly, adopting a cooperative model in the dairy sector can empower small-scale farmers and ensure fair compensation for their produce. By establishing village-level dairy societies and a robust supply chain, Pakistan can create a more equitable dairy industry. Secondly, investing in research, innovation, and product diversification. Amul’s portfolio, can help in setting a path to cater to changing consumer demands and enhance the value proposition of dairy products. Additionally, effective marketing and branding, as exemplified by Amul’s iconic advertising campaigns, can boost consumer trust and brand recognition. Pakistan should focus on the social and economic impact of its dairy industry, emphasizing rural development, women’s empowerment, and improving the livelihoods of millions of rural families. By learning from Amul’s journey, Pakistan can create a thriving and sustainable dairy sector that benefits both farmers and consumers.

The future of Pakistan’s smallholder dairies lies in the hands of those who are determined to protect them. The challenges are immense, but so is the spirit of resilience. As the sun sets over the rural landscapes of Pakistan, it also rises with hope and determination.

It is time to turn the struggle for smallholder dairies into a national movement. Across provinces, languages, and communities, the call to protect these farms must resonate. Small farmers, urban consumers, policymakers, and international allies must come together. By collaborating, they can address the multifaceted challenges faced by Pakistan’s smallholder dairies. Innovative solutions rooted in tradition can help smallholder dairies thrive. Modernizing practices while preserving cultural heritage is key to ensuring the sustainability of these farms. The resilience of smallholder dairies has endured through the ages. With collective effort and unwavering hope, the future can be one where these farms continue to flourish.

The struggle to protect Pakistan’s smallholder dairies is a story of resilience, culture, and the enduring spirit of a nation. As we write the epilogue of this narrative, we can choose to preserve a legacy—a legacy that nourishes the land and its people. It is a legacy of smallholder dairies that withstand the test of time, safeguarded by a united front of those who understand their value. The story is far from over, but it is a story that Pakistan and its small farmers can continue to script together. The legacy of smallholder dairies, deeply etched in the nation’s history, culture, and future, is a testament to the power of collective action, determination, and the will to protect what matters most.

Sustainability is the cornerstone of the future of Pakistan’s smallholder dairies. Small steps taken today can create a lasting impact for the generations to come. Promoting agroecological practices within the dairy sector is crucial. These sustainable farming methods not only protect the environment but also ensure the well-being of livestock and farmers. Encouraging the growth of local and organic dairy markets can be a game-changer. Consumers are increasingly seeking natural, healthier dairy products, which can empower smallholder dairies. Investing in education and innovation at the grassroots level is essential. Training small farmers in modern practices, enhancing their knowledge of dairy nutrition, and introducing new technologies can boost productivity while maintaining traditional values. Ensuring that smallholder dairies have equitable access to resources such as land, water, and finance is pivotal. This can be achieved through well-structured government policies and financial support.

The battle for smallholder dairies is not unique to Pakistan; it’s a global fight. Standing together with small farmers worldwide, Pakistan can be part of a global movement for their protection. Pakistan can extend a hand of solidarity to smallholder farmers in other nations, learning from their experiences and sharing their own. By standing together, the voices advocating for small dairies grow stronger. The international community can play a crucial role in supporting Pakistan’s smallholder dairies. By advocating for fair trade policies and investing in sustainable agriculture, a global network can uplift small dairy farmers. Pakistan can foster knowledge-sharing initiatives with nations facing similar challenges. Exchanging best practices and innovative ideas can lead to a brighter future for smallholder dairies.

At its core, the future of smallholder dairies hinges on the choices made by individuals, communities, and policymakers. It is a matter of choosing tradition over convenience, resilience over surrender, and unity over division. Consumers have the power to reshape the dairy industry by choosing to support smallholder dairies. Opting for fresh, local dairy products can preserve tradition and empower small farmers. Communities can rally behind their local farmers, strengthening the bonds that sustain smallholder dairies. Initiatives that connect urban and rural areas can bridge the gap between consumers and producers. Policymakers hold the key to creating an environment where smallholder dairies can thrive. By enacting laws that protect and promote these farms, they can secure the future of millions of small farmers. The choices made today will shape the world of tomorrow. Pakistan stands at a crossroads, and the path it chooses will determine whether the legacy of smallholder dairies lives on or fades away.

In the years to come, as we look back on the struggle for Pakistan’s smallholder dairies, we may find a vision realized. The nation’s commitment to sustainability, global solidarity, and the power of choice can pave the way for a brighter future. The legacy of smallholder dairies can stand strong, a testament to the resilience and unity of a nation that chose to protect what mattered most. This is a legacy that Pakistan and its small farmers have scripted together—a story of hope, determination, and the enduring spirit of a people.