The phrase annus horribilis was perhaps most famously used in 1891 in an Anglican publication to describe 1870, the year in which the Roman Catholic Church defined the dogma of papal infallibility. It was brought into prominence in modern times by Queen Elizabeth II in 1992 when the royal family faced a large number of scandals involving Princess Diana’s marriage, divorces of other royal members and a fire at the Windsor Castle. Most historians of the future will agree that 2020 can be truly described as annus horribilis for the entire humanity. Pakistan also suffered like the rest of the world, but in some ways it got off relatively less miserably. There were fewer cases of COVID-19, as well as deaths. Its economy suffered comparatively less and declined by -0.4 percent, as against the United States which declined by -4.3 percent, the European Union (EU) by -12 percent, the United Kingdom by -9.8 percent and India by -10.3 percent.

This COVID-19-related economic decline naturally impacted international relations in different ways. Pakistan’s balance of payments problems became acute, increasing our dependence on our friends who fortunately did come through; it also highlighted some of our vulnerabilities, particularly in our dealings with our closest Muslim friends. This piece, however, deals with our relations with India. The events of 2020 will cast a shadow on Pakistan’s external relations in 2021.

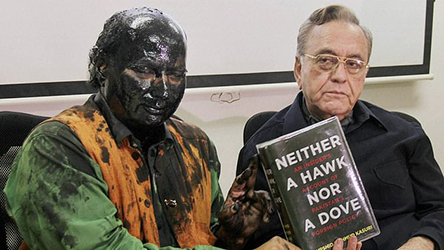

I have indicated in my book Neither a Hawk, nor a Dove that, based on my experience in dealing with Prime Ministers Atal Bihari Vajpayee of the BJP and Manmohan Singh of the Congress, the only way forward for Pakistan and India is to rationalise their relationship and encourage regional cooperation. Experience has taught us that this can only happen if we solve the Kashmir dispute according to the aspirations of the people of Jammu and Kashmir (J&K), and further that it should be a win-win for all. This is possible only though a sustained dialogue. The conditions for such a dialogue do not currently exist. It is unlikely that Pakistan’s relationship with India will improve in any substantial manner while Prime Minister Modi is in power, because, both he and the current BJP leadership, find that polarising India’s polity pays rich political dividends. This is why we see phenomenally increased hostility towards Pakistan and Indian Muslims during election campaigns for all national or state elections.

The BJP’s politics, based on its Hindutva ideology, has polarised this heterogeneous country, raising fear and tension among Muslims and even other minorities. Mob violence against Muslims, who make up about 14 percent of India’s population, and lower-caste Hindus has reached alarming proportions. The Modi government has managed to subdue all state institutions including the Supreme Court, the media (with some honourable exceptions), and the bureaucracy, which is being openly used to cow down its political opponents. Ironically, one side-effect of this has been the realisation by the masses that they need to take matters into their own hands to be heard. There have been three huge displays of defiance by the public, namely, on the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA); the lockdown call by PM Modi following COVID-19 which was flagrantly violated by migrant labourers, who continued to walk on the roads for weeks; recently we have seen unending protests by farmers, who are openly defying the writ of the government.

The use of polarising tactics (which has an impact on India’s relations with Pakistan) referred to above, is compounded by the fact that under India’s political system, there is a continuous series of elections in different Indian states throughout the five-year tenure of the Union government. In view of this, it is unlikely that Pakistan’s relations with India will improve in any meaningful manner during the dispensation of the present ruling elite. Although, there is a spate of elections to different state assemblies, in West Bengal, which adjoins Bangladesh and where 30 percent of the electorate is Muslim, the elections that are due in May 2021, are of particular significance. The BJP attaches great importance to the Bengal elections and, for this purpose, has even put its relationship with Bangladesh at stake. It has termed immigrants from that country as “termites.” This has had a very negative impact on public opinion in that country and has resulted in a cooling off of its relationship with India. PM Modi will meet his match in the Chief Minister of Bengal, Mamata Banerjee of the All-India Trinamool Congress. She is a very strong leader and has a formidable reputation. If she is able to retain Bengal and stop the BJP juggernaut, there is a possibility that PM Modi may be tempted to rethink his highly polarising politics. This could have an impact on India’s relations with Pakistan.

India has realised that it had been unable to cow down the Kashmiris with its brutal tactics and if it does not mend its ways, in 2021, they may adopt a more violent course

Already there are indications that PM Modi has started realising the negative consequences of his policy. This is illustrated by his recent remarks in an address delivered at the centenary celebrations of Aligarh Muslim University, which were aimed at placating the students, the faculty and Muslims generally. Compare this with the harsh treatment meted out during the agitation against the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), where the police entered the hostels and mercilessly beat-up the students. Perhaps, PM Modi has been told that his policies have negatively impacted the Muslim world generally. At different times, India made special efforts to improve its relations with Iran, Turkey and Malaysia, which have all reacted very negatively to BJP’s policies and its treatment of Muslims. India’s attempts at cultivating the Gulf countries, as well as Iran, Turkey and Malaysia, were aimed at creating problems for Pakistan. There have been indications that Saudi Arabia and the UAE have conveyed to India privately, that they find it embarrassing to keep quiet at India’s treatment of Muslims.

As far as Kashmir is concerned, India has realised that it had been unable to cow down the Kashmiris with its brutal tactics and if it does not mend its ways, in 2021, they may adopt a more violent course. There are indigenous Kashmiri organisations like Hizbul Mujahideen, who will be tempted to further strengthen their armed struggle for liberation. There is also, of course, the Daesh which advocates an even more violent course of action. Pakistan should keep away from any activity which can be laid at its doorstep and be used by India to delegitimise the genuine struggle for liberation being waged by Kashmiris.

For all intents and purposes, India has lost the Kashmiris. PM Modi’s act of abrogating Article 370 has been widely condemned. There has never been such widespread criticism in the western media, human rights organisations, members of the EU, British parliamentarians, US Congressmen and think tanks against Indian policies in Kashmir. This criticism is all the more important because the West wishes to build up India as a bulwark against China. Furthermore, Pakistan has succeeded in raising the issue at the UN Security Council (UNSC) — albeit in closed sessions — with the help of its all-weather friend, China.

The recent District Development Council (DDC) elections in J&K which were, of course, largely boycotted by Kashmiris even without an actual boycott-call by the Hurriyet leaders, have resulted in a sweeping victory for the ‘Gupkar’ coalition, comprising the National Conference, the Jammu and Kashmir Peoples Democratic Party (PDP) and others. Mehbooba Mufti has commented that the results of the DDC elections have made it clear that the people of Jammu and Kashmir have rejected PM Modi’s unconstitutional decision to abrogate Article 370.

We can expect that PM Modi’s policy of hostility towards Pakistan will continue in 2021. Although, some military commanders in India have said that India is prepared for a ‘two-and-a half front war’ (against Pakistan, China and the people of Kashmir), most serious-minded defence analysts (even in India) regard this as totally impractical and foolish. Some people in Pakistan feel that because of Modi’s growing economic difficulties, he might try to divert attention through a military confrontation with Pakistan. I do not think that PM Modi will commit such a blunder because Pakistan is not just a nuclear power, but it has one of the largest battle-hardened armies in the world.

In 2021, we can expect these attempts to ‘contain’ China being made by the US and India’s eagerness to play ball.

Literature on the subject, including books by British, American and Indian authors, makes it abundantly clear that India cannot win a conventional war against Pakistan. For example, in December 2020, Dr. N. C. Asthana, a former officer of the Indian Police Force and author of 48 books who is regarded as an expert on security matters, in his book National Security and Conventional Arms Race: Spectre of a Nuclear War has concluded that “India has no clarity about its military and strategic objectives vis-à-vis its stated adversaries, Pakistan and China, and can defeat neither of them in a war.” Recently, Shekhar Gupta, one of India’s leading columnists, said that “the Balakot strike and the skirmish the day after was the first warning that India had allowed its edge to fray over time. In the air, for example, the Pakistan Air Force (PAF) out-ranged the Indian Air Force (IAF) in Beyond Visual Range (BVR) missiles and more than matched it in Airborne Early Warning (AEW) resources.” I would also like to quote here from Not War, Not Peace? a book published in India and written from an Indian perspective by George Perkovich and Toby Dalton: “India and Pakistan are approaching rough symmetry at three levels of competition: sub-conventional, conventional and nuclear. One of the countries may be more capable in one or more of these domains to deny the other confidence that it can prevail at any level of this violent competition without suffering more costs than gains. The condition of rough balance and deterrence across the spectrum of conflict amounts to an unstable equilibrium.” Similarly, Pravin Sawhney, defence analyst and former Indian Army officer in his book Dragon on Our Doorstep, says, “With the Pakistan Army having plugged existing conventional gaps, a war between India and Pakistan is not possible. In order to meet the Indian Army’s Cold Start Doctrine challenge, the Pakistan Army has taken two steps, one declaratory and the other meant to strengthen its conventional war capability. As we have seen, Pakistan has altered its nuclear doctrine from minimum deterrence to full-spectrum deterrence with the announcement of tactical nuclear weapons to stop India’s purported mechanised offensive at the border itself. More relevant is its new concept of utilisation of Pakistan Army reserves…”

We can, therefore, expect different forms of hostile actions, short of war, by the Modi government against Pakistan. Firing across the Line of Control (LoC) in which Muslim Kashmiris are the prime sufferers will unfortunately continue, since PM Modi finds it politically useful to his base to give an impression of toughness in dealing with Pakistan. The Pakistan Army, does respond to the Indian firing, but it has to be careful about casualties of Kashmiri Muslims on the other side of the LoC. The efforts during my tenure in government (November 2002-2007) helped to usher in a period of ceasefire on the LoC in 2003, which lasted for almost 10 years.

India is already engaged in a very risky exercise of using its assets in Afghanistan to destabilise Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan. The details have been disclosed in the dossier presented by the Foreign Minister and the DG ISPR to the media, which reveal that India is trying to encourage Daesh, as well as, the Tehreek-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), to launch attacks across the border. The frequency of such attacks has increased in the recent past, leading to the martyrdom of Pakistani soldiers. This is generally regarded as an expression of the ‘Doval Doctrine,’ whereby India is supposed to be responding to its difficulties in Kashmir. There is a big risk here. How long will Pakistan be able to accept this damage without retaliating? It has different means at its disposal, but it is best not to go into details. It is about the right time to present to the international community the reverse narrative of India as a state-sponsor of terrorism. India had successfully painted Pakistan into that corner for the uprising in Kashmir, taking advantage of the West’s antipathy to all forms of violence following the events of 9/11, even if they be for national liberation. Pakistan has a big diplomatic challenge on its hands, but the dossier can be helpful in that connection provided Pakistan makes effective use of strategic communication.

As regards Indo-China relations, we can expect tensions between India and China to continue in 2021. The Chinese army has dug in for the winter across the Ladakh border, tying down the Indian troops on the other side and providing some relief to Pakistan. Diplomatic efforts, as well as talks between military commanders of the two sides to reduce tension, have failed. Recent actions by India, following the abrogation of Article 370 and the division of Kashmir into two union territories, has in some ways made China a third party to the Jammu & Kashmir dispute. After India’s recent actions, China criticised India for “unilaterally” changing the status quo in Jammu & Kashmir and asked both Pakistan and India to resolve the dispute “based on the UN Charter, relevant UN Security Council resolutions and bilateral agreements.” Additionally, the Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi was brutally frank on Ladakh and told India’s External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar that India’s action “has posed a challenge to China’s sovereignty and violated the two countries’ agreement on maintaining peace and stability in the border region.”

It is because of the reckless statements issued by India’s top leadership that India will capture Azad J&K, Gilgit-Baltistan and Aksai Chin that India is confronted with the current situation. Clearly India has provoked China. It is noteworthy, that India has been building infrastructure right next to the Line of Actual Control (LAC) for quite some time. In the past, China had not publicly objected to this. It is India’s recent actions and the statements by the Indian leadership in their meetings with the leadership of the QUAD (US, Japan, Australia and India), along with other actions and statements, that gave a clear impression that India would be a willing party in this attempt to ‘contain’ China that sent alarm bells ringing.

In 2021, we can expect these attempts to ‘contain’ China being made by the US and India’s eagerness to play ball. Certain defence agreements with the US in the recent past and statements and actions following the 2+2 talks between India and the United States gave the same impression. It was the statements, followed by recent actions in J&K, followed further by the publication of a political map, which upset the leadership in Beijing. Consequently, they started regarding the development of Indian infrastructure right up to the LAC and Karakoram pass, as part of India’s grand design to threaten China, Pakistan and the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC).

How should Pakistan respond to the present situation?

Firstly, a Strategic Communications body should be set up, led by the Prime Minister himself, that should incorporate key communication officials of the state and specialists from the private sector, who have a grip on what type of narratives find traction. Media and communications is a science and it cannot be left in the hands of those who are not trained and specialised in this field. This body should comprise young people who are more adept at using the latest communication tools.

While Pakistan must continue to provide diplomatic support to strengthen the peaceful resistance of the Kashmiris, it must ensure that its territory is not used by anyone to engage in any misadventure that could enable India to shift global attention from its own repression

Secondly, there should be a sustained diplomatic effort on Kashmir. It needs a sustained, proactive diplomatic engagement by Pakistan. For example, the speech by the Prime Minister at the UN General Assembly session (September 2019), in which he highlighted the Kashmir issue, was not sustained subsequently through focused diplomatic efforts. Furthermore, we need to focus our attention on a few countries, instead of wasting our resources. There are three major news dissemination centres in the world: New York, London and Paris. Specialists in communication should be attached with the embassies there through their information desk, so that they bring some freshness and enthusiasm into promoting the new narrative.

Additionally, we should focus on special groups like human rights organisations, members of the EU and the British parliament, US Congressmen and think-tanks. Among these groups, we can find people who are sympathetic to the plight of the people of Kashmir. This is true even in countries, where their governments prefer to keep quiet in their perceived national interests. Simply engaging with government leaders and foreign offices in different countries is not enough.

While Pakistan must continue to provide moral, political and diplomatic support to strengthen the peaceful resistance of the Kashmiris, it must ensure that its territory is not used by anyone to engage in any activity or misadventure that could enable India to shift global attention from its own repression. There is no appetite for non-state actors in the international community. The government of Pakistan has taken certain concrete steps in this respect. Regardless of what Pakistan does or does not do, if India persists with its oppressive methods it will, most likely, meet two types of resistance inside Jammu and Kashmir anyway. Firstly, indigenous Kashmiri organisations like Hizbul Mujahideen will be tempted to further strengthen their armed struggle for liberation. Secondly, there are bound to be people who will follow a more violent course advocated by Daesh and take up arms. Pakistan has already alerted the international community that India, for its own ulterior motives, is trying to use some elements of Daesh to destabilise Pakistan.

The Pakistani and Kashmiri diaspora should be mobilised more effectively. We have seen recently that they are well-represented and organised in many North American and West European capitals.

While advocating the above, we have to be mindful of a very interesting phenomenon in occupied Jammu and Kashmir in recent times. The Indian government announced that things were back to normal and that schools ought to open. A large number of parents responded by not sending their children to school. The government then announced that it would like the shops to open; a very large number refused to do so. Ironically, a section of Kashmiris seem to be practicing Gandhi’s techniques of non-violence against those who hate Gandhi, namely, the RSS and the BJP. Pakistan should highlight this aspect of the Kashmiri struggle as well. The resistance movement in Kashmir will take many shapes and forms, and those opting for violence to attain their objectives have not needed any external help; this is now generally accepted. However, the non-violent method of resistance in Kashmir should also be highlighted. This will generate sympathy and support for Kashmiris internationally.

As part of the strategic communication, it is essential to maintain credibility. India’s gross violations of human rights have been covered in detail by various credible human rights organisations. It has been observed that on certain occasions our top officials have given contradictory figures. This creates a very bad impression of Pakistan’s interlocutors, who are, anyway, well-briefed by their own sources. In order to be credible, figures should be completely accurate and should preferably rely on foreign commentaries critical of PM Modi’s policies and actions. Exaggerated figures by Pakistani sources must be avoided.

The Pakistani and Kashmiri diaspora should be mobilised more effectively. We have seen recently that they are well-represented and organised in many North American and West European capitals. Greater attention needs to be paid to such groups.

Foreign delegations sent abroad should consist of credible persons from the government, the opposition, the academia, as well as the media. Sending unqualified people on foreign junkets is counter-productive.

It is extremely dangerous when politicians play with public sentiments in dealing with external relations

Last but not the least, and most importantly, we have to strengthen Pakistan’s polity and economy. In the ultimate analysis, we have to strengthen Pakistan and rehabilitate its image, which has taken a huge battering during the last three to four decades for various reasons. Luckily, certain decisions have been taken by the civil and military leadership, which are beginning to slowly alter the narrative. We must all work to adopt policies that will make Pakistan economically strong again. After all, for almost four decades Pakistan’s GDP growth rate was appreciably higher than that of India’s. We cannot be permanently begging for money to balance our budget and hope that it will not adversely affect our international standing.

In this context, it is necessary to point out that the internal situation has a major bearing on the conduct of foreign relations. The nineteenth-century British Prime Minister William Gladstone aptly remarked, “Here is my first principle of foreign policy: good government at home.” Coming to more recent times, President-elect Biden has said that, “Foreign policy is domestic policy, and domestic policy is foreign policy. They’re deeply connected.” In a democracy, no foreign policy can succeed unless it enjoys popular support. Therefore, it is the prime duty of a government to truthfully convey the realities to the people and galvanise national consensus around it.

It is extremely dangerous when politicians play with public sentiments in dealing with external relations. The current crisis in Pakistan’s internal politics is very worrying. At a time, when PM Modi has not made any secret of his hostile intentions towards Pakistan, it is distressing to see a total breakdown of relations between the government and the opposition. It is essential that a dialogue resume as soon as possible. Since it is now generally accepted that the establishment plays a major role in certain aspects of internal polity, the government, the opposition and the establishment must do all that it takes to present a united front at a time when Pakistan is confronted with an openly hostile neighbour. I expect 2021 to be a period of tension, and all other considerations among Pakistan’s political elite need to be made subservient to this factor.