Tumhein fikr hai apne ghar ki

Mujhe har gali ka gham hai

This heartfelt couplet by people’s poet Habib Jalib encapsulates the soul of this activist-academic piece of work edited by Nida Kirmani, comprising nine papers presented at a conference in Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS) in 2016 with an afterword by trailblazing urban studies’ specialist Nausheen H Anwar. Marginalisation, Contestation, and Change in South Asian Cities aims at unveiling the pertinent and negative effects of neoliberalisation/marketisation in urban transformation of South Asian Cities. The papers are mainly about Indian and Pakistani cities experiencing urbanism in the form of marginalisation, exclusion, segregation and changing the imagined connectedness of their people from the landscape they have inhabited for decades. This lucid book argues that the phenomenon of converting urban landscape into ‘world-class’ or megacities causes displacement of the urban poor or snatches away their familiarity, usage of resources from the land they occupy along with many other vagaries of such sort and the resistances that these changes accompany.

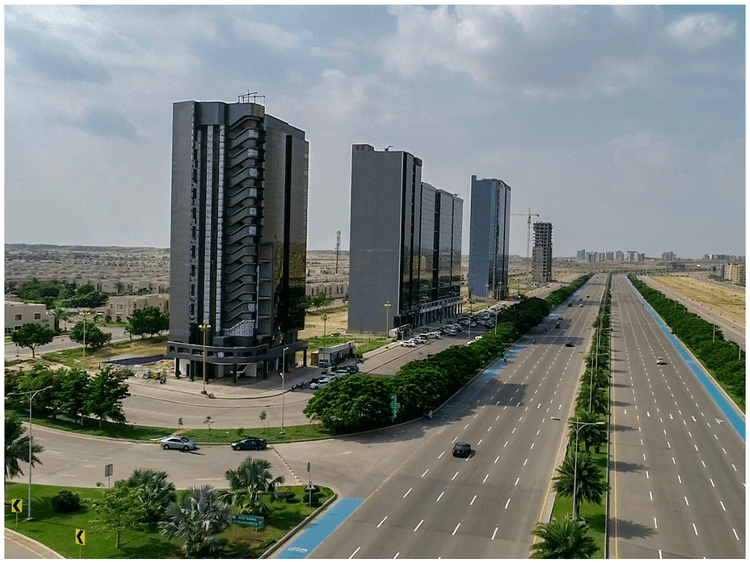

The first paper titled “Entangling the Global City: Everyday Resistance in Gadap, Karachi” by Shahana Rajani and Heba Islam talks about how Bahria Town has erased from the public memory that a local community has existed and still inhabits beyond its boundaries. The new vision envisioned for Gadap isn’t a clear-cut process but an entanglement whereby ‘progress’ and ‘development’ lead to violence and erasure. The architecture, visuals and the materiality that the new geography brings, are analysed while making a point about the development of Bahria Town serving as forgetting and erasure that doesn’t only relegates the locals to the past but also tries to make their spatiality non-existent. The chapter alludes that Bahria Town’s utopic existence as a global city aims to identity itself as the future and the local as the past. These kinds of ventures are illusory that use a glossy outlook to hide the remnants of the previous residents. Hence, Bahria Town, an initiative for urban transformation, sets out to present ‘the world-as-exhibition.’ Over here in the paper, the larger phenomenon of the ongoing erasure of indigenous landscape and histories is revealed as one of the methods of enacting structural violence, historically, where the post-colonial state tries to put forth policies that discriminate and displace the indigenous people of the city.

The second paper “The Case of LDA City: How a Public-Private Partnership Fractured Farmers’ Resistance in Lahore” written by Hashim bin Rashid and Zainab Moulvi presents the case of LDA city scheme which is to be Pakistan’s ‘biggest housing scheme’ in southwest Lahore spanning 64,000 kanals. The formation of such schemes involves plunder of rural land on the fringes of the city by acquiring it at cheap prices and converting it into high-value real estate—usually in the shape of elitist residential areas. The LDA is representative of a profiteering developer while also being regulator of housing schemes after entering this phase of extremely ‘lucrative’ game of housing schemes. The urban developing authorities have also taken away power from the local governments. There is fractured resistance as a response to dispossession posed by the development of the LDA city due to the infrastructure in place and not because of the state force only. With acceptability towards selling of agrarian land through the private-public partnership, the ones left resisting, feel helpless in the face of usurpation of their land. The sense of dispossession turns the urban citizen as primarily a ‘market subject.’

The third paper titled “Looking at the City from Below: Contribution of ‘Access’ Approach and ‘Cityscapes’ in Amritsar” by Helena Cermeno while talking about urban development at a place Jhuggi Mokhampura in Amritsar raises an important point that the development planning visions and policies are borrowed by neoliberal trends and the already marginalized residents face hindrances in accessing resources leading to further exclusion. This legal development venture and others of this sort aim to reproduce marginalization and unjust spaces in the city by resettlement of people residing in Jhuggi Mokhampura for the creation of ‘low-income’ housing where the residents can although take advantage by the services provided/power relations between residents and municipality officers, pardhans (local leaders), local politicians, these allotment plans don’t ensure access to enough living space, basic facilities such as electricity, water, sewage, and drainage, and the city space at large.

The above three chapters and case studies talk about urban planning purposely congregate and segregate urban poor or dispossess them from their land to build elite conclaves. The former means non-access to employment opportunities and cut them off from the city, pushing them further into the fringes. These chapters are a significant intervention for explaining inequality due to neoliberal transformation but are repetitive at times and are unable to capture the texture of the cities under study leading to rendering case studies indistinguishable in form not in content, indeed though. However, the case studies of demolition of squatter settlements of Gujjar and Orangi Naala in Karachi and razing off katchi abadis in Islamabad in the name of ‘world-class’ urban transformation, perpetrating unequal actions by the state should have been added and addressed while talking about change in conception of cities’ landscape.

“Bolstering Security by Erecting Barriers and Restricting Access: The Case of Karachi” by Noman Ahmed is the weakest of the lot and lost the opportunity to talk about the militarisation of Karachi over the years due to security threats; the only takeaway from the paper is that installation of containers and barriers, initially meant to be temporary, now seem to be permanent part of the city and restrict mobility of the commoners while providing elite with the ‘golden’ chance to create a city within a city. The author could have benefitted by illuminating the inequality depicted due to this phenomenon as well as the ranger-ridden landscape that instills a sense of fear amongst the Karachiites at large, and at times also leading to racial profiling of ethnic and religious minorities.

Asad Sayeed and Kabeer Dawani’s “Mafia Domination or Victim of Neoliberalism? Contextualising the Woes of Karachi’s Transport Sector” draw our attention to depleted transport system in Karachi with the existing public transport infrastructure falling excessively ‘short of the demands of the city.’ Karachi’s population has doubled over last two decades, but the number of buses remain static. They claim Karachi is one of the few ‘megacities’ in the world without a planned system of mass transit. A pertinent reading in this paper about the reason for lack of effective governance in the city in general and specifically a lack in provision of public services such as the public transport is due to the ‘partisan role of the state in violent conflict across ethno-political lines’ implying that the local state or government has lost its legitimacy over monopoly on violence eroding the writ of the state. The authors recommend that an affordable and effective public transport system can only be made possible when the Pakistani state focuses on socio-economic equity in terms of urban development as opposed to the maintenance of law and order and aiming at gaining short-term profits.

The urban regions in South Asia are experiencing transformation that have significant environmental ramifications. Due to the drive towards unabated economic growth has become toxic for the region making the cities unlivable. This ‘toxic urbanism’ is explicated by Rohit Negi and Prerna Srigyan in their paper “In the Time of Toxic Air: Environmental Contestations, Collaborations, Justice in Delhi.” Toxic urbanism is basically the linkage of urbanization and willful environmental change in South Asian cities and the case under study is Delhi over here. The authors shed light on the formation of new collectives around air which are beyond the already existent environmental advocates; these collectives and collaborations include diverse ‘publics’ producing expertise around air. Therefore, the environmental discourses across urbanisation are now being problematised. Environmental concerns have now entered the mainstream. Air itself has taken the shape of political agency where governments are enforcing ‘rationing of road space,’ experts debating ‘emission norms’ and those who can afford are investing in air purifiers. The local government, judiciary and civil society organisations are now taking environmental justice positions as opposed to the dream of converting Delhi into a world-class city. However, the paper draws our attention towards the fact that public conception of the air is nevertheless making it an individual and household-scaled phenomenon majorly benefitting the elites as opposed to air being a shared entity.

“Electoral Politics in Delhi’s Informal Settlements: Contestation, Negotiation, and Exclusion” by Shahana Sheikh, Sonal Sharma and Subhadra Banda shed light on the kind of contestation and negotiations take place during election period in Delhi, the centre of analysis being informal or squatter settlements. They elucidate that the informal settlements’ residents are manipulated through promises of basic service delivery again and again with ad hoc measures, but no fulfillment of their electoral promises made during election campaign. The political parties, hence, use the insecurity created as a result, to their advantage, making unfulfilled promises in order to win votes but then keeping the people in the constituencies deliberately hungry until the next election arrives, and this is a repetitive phenomenon. This remains the most interesting chapter of the book because of the intelligent linkage of electoral politics with the unfulfilled developmental promises which is ubiquitous all-over South Asia.

Chapter eight by Pinky Chandra and Kabir Arora talks about the transformation of waste into a resource with a focus on the informal waste economy in Bangalore and the players involved. Actors in the waste economy, although often neglected by the rest of the city and policymakers, are focal players in the ‘infra-economy’ where they provide necessary environmental services.

The last paper “Studying in the Mahol: Middle-class Spaces and Aspiring Middle-class Male Subjects in Urban Pakistan” is a promising interweaving of gender politics with environment as well as the class dynamics, presenting a new theoretical framework. This is written by Muntasir Sattar. The imagination of transforming Lahore into a Paris-like model leads to a deeper change that is beyond infrastructural and state-led development. One of the signs of it the formation of -single-sex hostels in Lahore’s crowded transit hubs. They mainly cater to the migrants from far flung areas from all-over Pakistan aspiring to become educated, university-educated expanding middle class milieu. These hostels are reflective of the ways in which they link some of the larger socio-economic processes in place in Lahore and an emerging class of men who are cultivated to be an urban and cosmopolitan subject through their acquisition of education, primarily in CSS qualification. It provides them with the chance to leave their village and form an experience of their own to be recognized as a ‘student,’ a respectable designation than being termed unemployed. Therefore hostels, the mohalla is a complex space of social formation which plays a large role in how young men aspire to become successful middle-class subjects within a precarious urbanizing future.

To conclude, the attempts to make ‘cities of lights’ into ‘cities of darkness,’ ‘darkness’ representing the negative impact of urbanism which is counter-productive for already neglected citizens as well as the anti-people or pro-neoliberal policies. This book is an adequate and much-needed response to the change occurring in the Global South, trying to mimic the developed cities, most importantly when there is a dearth of scholarship and debate around the phenomenon. Therefore, it’s a big thumbs up for this piece of work, from my end!

Publisher: Oxford University Press, Pakistan (OUPP)

Pages: 218

Price: Rs 695