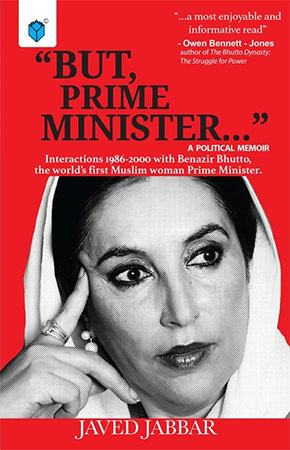

Author: Javed Jabbar

Publisher: Paramount Books Pages: 560

Price: Rs. 1,035

Taken on the holistic level this is an engaging and highly informative book that any respected international press should consider a good collection to their general repertoire. Javed Jabbar writes clearly and in fluent English, and barring a couple of minor errors here and there the draft itself is erudite and comprehensive. Its subject: the incomparable Benazir Bhutto.

But comprehensive from what perspective? Certainly Jabbar’s knowledge of governmental machinations and responsibilities is unquestionably highly-informed and hence intriguing. However, that should hardly surprise one given that he was an eminently respected Senator for six years. He saw more excitement during those two consecutive three-year Senate terms than most men would in a lifetime. In Ancient Rome the Senate held the now-legendary role of keeping the wildly potent emperor in check — sometimes successfully in the case of Claudius, sometimes more problematically — as in the cases of Nero and Caligula (although it is entirely possible that both are victims of propagandist revisionist history). As a member of the gubernatorial Upper House Javed Jabbar held his own respectably against the unpredictable tides of Pakistani politics. And also against a well-meaning woman, who while not precisely a female Nero had her moments of imperial instability. The number of times Jabbar recounts receiving an angry phone call from her over a matter which he ostensibly at least had under control, is sobering.

The book underscores implicitly that Javed sahib was far more comfortable with the elite and respected civil service required by senatorship than he was by his ministerial duties. He was also more comfortable in aggregate dealing with the PM (Benazir) than he was with her husband. That is unfortunate, because had he not had an apparently minor run-in with the redoubtable Hakim Ali Zardari (mentioned early in the book) and had he assiduously cultivated a relationship with his son Asif (that Jabbar, for better or for worse, appears not to have done) his life would have been made much easier. And his standing in the PPP (Pakistan People’s Party) would have been far better cemented. He should ideally have been made federal minister, and although he did not get that post, his handling of the challenges and intricacies of broadcasting and information under the aegis of the ministership personally granted to him by the PM was effectively handled by him.

Although Benazir listened to him up to a certain point, one does not even need to read between the lines in order to determine that her attitude towards this respected author bordered on presumptuous, occasionally even feudal. But can she be blamed for that given that she was intrinsically as much a feudal as her father and brother? Well, Jabbar’s Western audience would have appreciated this much better were he to have included a couple of paragraphs on her position as Sindhi feudal girl. He delights in placing her in a type of chessboard opposition to both Ghulam Ishaq Khan and Altaf Hussain (at different junctures) but fails to mention in his uncomplimentary Pandora’s box list of how inferior Altaf was to the PM the one trump card that makes life easier for any Pakistani politician/figurehead, and which Altaf did possess: the Y chromosome! Jabbar does not need to coyly hint at GIK being chauvinist (the Pathans almost pride themselves on that); he should have just come out and said it. But I suppose that would have compromised Senator Jabbar’s elegant diplomacy. Given his temperament and knowledge of politics and international relations he is true ambassador material. Few people can doubt that Jabbar displays the type of international flair that enables him to be as at home with affairs of Antarctica as those of Brazil.

Thus, perhaps Benazir’s love-hate relationship with her minister stemmed from the fact that she resented his position as a male — albeit an educated and enlightened one, possessing both talent and shrewdness. The dinner scene with Murtaza Bhutto is notably dramatic, but any clued-in reader will pick up on the fact that Murtaza in spite of his terrorist past eventually reformed to the point where he was far tamer a force than the combo of his sister and her husband. The reference to Zardari’s awkward foot placement during the Saudi visit is a minor point — and former President Zardari deserves a more complimentary adjective than “tentative” for the US visit.

Jabbar describes his tireless efforts for improving the plight of humanity — be it at Tharparkar or in major global arenas. He deserves more credit on those fronts than his modesty permits him to allow himself. His guilt at being put up in the Waldorf Astoria, given the poverty of his country, is perfectly sincere. Many political authors would not have given this point a second thought. That he did is commendable. Equally worthy of praise is his grace in the face of personal trauma — indeed, the scene where his aged father-in-law is ready to shoot and kill to protect Jabbar’s daughter, Mehreen, is particularly poignant. The book would have benefited I feel from a brief anecdote about his barrister son, Kamal, as well.

Given the chaotic nature of Pakistani political history, the book is remarkably logical and well laid out, but then that is to be expected since Jabbar is a seasoned author. Western and Eastern readers alike will appreciate the confidential to semi-confidential manner in which he describes ministers being briefed daily. I was impressed by the fact that Jabbar (although as red blooded a male as any in the book) often — too often perhaps — swallowed his anger on many occasions — such as during the unfortunate scene where Naheed Khan did not realize that he was present when she lambasted his stance. This was a serious slip on her part.

The latter portion of the text takes a thrilling dramatic turn, especially in the Supreme Court episode where Jabbar personally goes up against a heavyweight lawyer like Pirzada. But few intelligent readers will glibly swallow the fact that Jabbar could not afford adequate legal representation. Neither will they buy into his defence of Pervez Musharraf as being incapable of ordering the cold blooded murder of the former PM. Someone well-versed in military and intelligence matters will easily and cynically perceive that the warning issued to Benazir prior to her assassination was a “gift” from the government, a gift that she should have accepted with grace and good sense.

Regardless, Jabbar’s detailed responses to Heraldo Munoz’s points centring on the theories around the assassination will alone be worth the price of the book. So too will some of his very insightful observations on our tensions with India. I found it impressive that both civil and military people were present at his briefing of the PM on super-sensitive Indian matters — their involvement might have been more a compliment to Jabbar’s position than he might personally think. One appreciates that there are limits as to what Senator Jabbar can reveal within a commercially published paperback. Indeed, there may have been serious limits placed (by himself) upon how he chose to portray things. While that is understandable, the fact that we get far more truthful information from this book on the late PM than we might from many eulogistic biographies of her is commendable.

The author is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Social Sciences, IBA, Karachi.