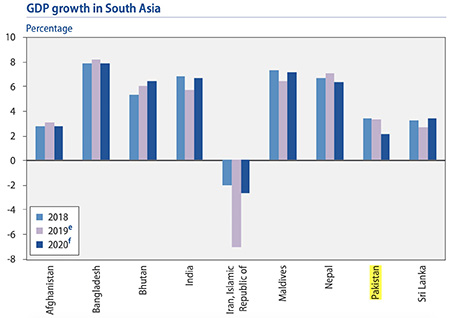

For 30 years Pakistan has been chasing the elusive goal of trying to become an economic powerhouse, like the East Asian Tigers. Instead, we are now drowning in debt and are stuck in an anaemic growth orbit — and we will continue to be a beggar state, since no government has seriously pursued the deep reforms that are needed to establish an economically strong Pakistan. It was unthinkable, 20 years back, that Bangladesh’s GDP (Gross Domestic Product) per capita in 2020 would be almost twice that of Pakistan. Bangladesh could be an economic powerhouse in 2030, if it grows at the same rate as in the past. If Pakistan continues its dismal performance, it is possible that we could be seeking aid from Bangladesh in 2030.

The blame for Pakistan’s poor performance lies at our own doorstep, but our leaders, and their economist supporters, have conveniently pushed the narrative that it is the IMF (International Monetary Fund) and the World Bank policies that are responsible for the mess we are in today. No doubt, the IMF/WB have often peddled “poorly thought out and one-size-fits-all” policies and bad loans. However, the deep hole that Pakistan is in, is largely Pakistan’s own doing. While corruption and the economic impact of terrorism have played a role, for the most part the poor performance is a consequence of pursuing irresponsible, inappropriate and unpredictable policies, and half-hearted reforms for long periods of time. The two most glaring examples of reckless policies were: excessive overspending by governments, financed by domestic and foreign debt; and imports far exceeding exports, leading to unsustainable external debt.

Bangladesh’s successful journey serves as a good example for learning lessons, since Pakistan shares similarities with it in terms of religion, poor work ethics, messy politics, bad governance, weak public administration, corruption at the top, elite capture etc. In just two decades, Bangladesh overtook Pakistan on key economic indicators. Its GDP per capita increased by 500 per cent — two-and-a half times that of Pakistan.

How did Bangladesh become a miracle story and Pakistan a disaster tale?

The socio-economic development story of any country is a complex phenomenon and unique to that country. However, one commonality among the democratic high-achievers is that over long periods they have, by and large, adhered to the key elements of the ‘Washington Consensus Policies’ — sound fiscal and monetary policies, liberalisation with focus on exports, targeted pro-poor expenditures — and reduced the role of the government in commercial activities. Interestingly, all high achievers also registered high levels of corruption.

Bangladesh encouraged savings over consumption. Its savings rate is around 30 per cent of its GDP, compared to 15-20 per cent for Pakistan. Pakistan’s irresponsible and impulsive policies encouraged public spending and import consumption way beyond what the country could afford.

In 2000, Pakistan’s exports were 50 per cent more than Bangladesh’s. Since then, the latter’s exports have risen by 700 per cent, almost three-and-a half times that of Pakistan. In 2020, Bangladesh’s exports were almost twice those of Pakistan. Bangladesh’s foreign reserves stand at $45 billion, twice those of Pakistan. On average, Pakistan’s exports only covered about 50 per cent of its imports, while the ratio is around 80 per cent for Bangladesh. Because of imprudent import and exchange rate policies, we have been foolishly incurring debt through foreign commercial loans, deposits and bonds, at high interest rates, to finance unnecessary imports. A stark example of this bad policy was when we imported cars and phones worth $3 billion and raised an equivalent amount by floating Eurobonds at high interest rates.

For most of the past two decades, Bangladesh’s fiscal deficit was around 3 per cent of the GDP, while Pakistan’s fiscal deficits were twice as high. Over 20 years, Pakistan’s cumulative per capita government spending was $4000, while Bangladesh’s was half of that. Despite our per capita spending being twice that of Bangladesh, our economic and human development indicators are worse than those of Bangladesh. We spent double for worse outcomes! Government spending in Pakistan has been reckless, based on the uninformed belief that higher spending leads to growth.

As a result of irresponsible fiscal and trade policies, Pakistan’s public debt is now close to 600 per cent of government revenues, which is twice that of Bangladesh. Additionally, bank lending to the private sector (as a percentage of bank lending to the government) is 200 per cent in Bangladesh and 80 per cent in Pakistan. Credit to the private sector is very restricted in Pakistan because of excessive government borrowings. Our external debt is 400 per cent of our exports — four times that of Bangladesh.

Pakistan’s FDI (Foreign Direct Investment) policies mostly encouraged investment in the service sector (eg telecom, power, construction), where revenues are in rupees whereas liabilities are in foreign currency. In comparison, Bangladesh aggressively promoted FDI in export manufacturing — in two decades close to $6-7 billion of the FDI was in textiles and garments.

Bangladesh’s economic miracle also benefitted from the separation of religion from the state, elimination of the military’s role in politics, and their leaders’ single-minded focus on Bangladesh rather than expending their efforts on championing the cause of Ummah.

It may hurt our national pride, but the only sure way for Pakistan to accelerate growth, reduce debt and avoid seeking aid is to emulate Bangladesh. There is no shortcut to success, except to consistently follow prudent fiscal and monetary policies.

Pakistan must take the following painful steps to live within its means: lower deficits to 3-4 per cent in 2-3 years, through a judicious combination of tax-raising, expenditure-management and privatising SOEs (state-owned enterprises); freeze total spending and domestic/external debt at current levels for a few years; strengthen the Debt Limitation Act to make it difficult for irresponsible policy-makers to circumvent the law. There must be a penalty on officials who approve violations of the law.

Taxing the wealthy should be the major pillar for raising revenues under the current circumstances, rather than going after the informal sector, which is the backbone of Pakistan’s economy. Pakistan should consider: a limited, duration-dedicated Debt Retirement Wealth Tax on individuals holding assets (urban/rural land and housing, vehicles, deposits and shares) worth over Rs 50 million; significantly increasing property taxes on property valued at more than Rs 50 million — to lead by example, the prime minister could start paying property tax on his “rural” Islamabad mansion; increasing taxes on goods consumed by the wealthy.

The politicised “war on corruption” should be turned into a “war on waste in government,” with savings being used for growth-inducing expenditures. SOEs should be privatised urgently. When the debt-to-GDP is around 100 per cent and debt servicing consumes over 50 per cent of the tax revenues, it is suicidal to increase government spending to finance SOE losses and untargeted subsidies — every additional rupee spent has to be financed by more domestic and external debt, thereby deepening the debt trap.

The deeply flawed 7th NFC (National Finance Commission) award, which has buried Pakistan under a huge pile of debt, needs to be changed. The provinces need to carry a proportionate burden of defence, debt service and subsidies, while the federal government PSDP (Public Sector Development Spending) should be limited to mega national projects only.

Pakistan must create a business environment — through changes in its taxation, credit, and ease-of-doing business policies — so that exporting is the “most profitable” business in the country and there is a “herd migration” of local businesses towards exports. Rather than piecemeal and band-aid initiatives, there needs to be a wholesale change to generate the “herd migration.” If we continue with our “business as usual” policies, we could end up seeking aid from Bangladesh in a decade or two. In order to establish an economically strong Pakistan, it is incumbent upon all political parties to develop a national consensus on fundamental reforms that are essential to accelerate inclusive growth and, at the same time, lower debt.

The writer is a former Advisor at the World Bank.