Historically, Karachi with a current official population figure of 16.05 million has had a high growth rate, way beyond the average national growth rate. Keeping aside the reasons for this spiralling growth and the authenticity of current official figures, this phenomenon exerts high demand on all aspects of civic life, including transport. The huge commutation requirements are demand-driven, satisfied by private and informal sectors, and define the housing and livelihood opportunities of city dwellers. Various Master and Strategic Plans have offered profound solutions to the transport woes of Karachi. Nevertheless, implementation is less than satisfactory.

The article reviews the five post-independence plans for Karachi, to document the planning and evolution of these sectors.

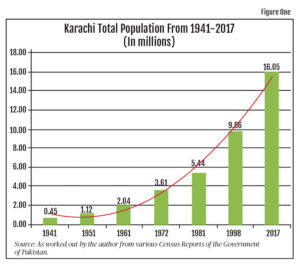

On the eve of Partition, Karachi had a population of 450,000 and with the advent of migrants from India it became 1.12 million (Census 1951). Though the recently conducted census of 2017 puts the official figure at 16.05 million, researchers and demographers contest the figures. Various media reports and documents claim that Karachi’s population is somewhere between 22 million to 25 million. Karachi’s population growth from the year 1941 to 2017 is depicted in Figure One.

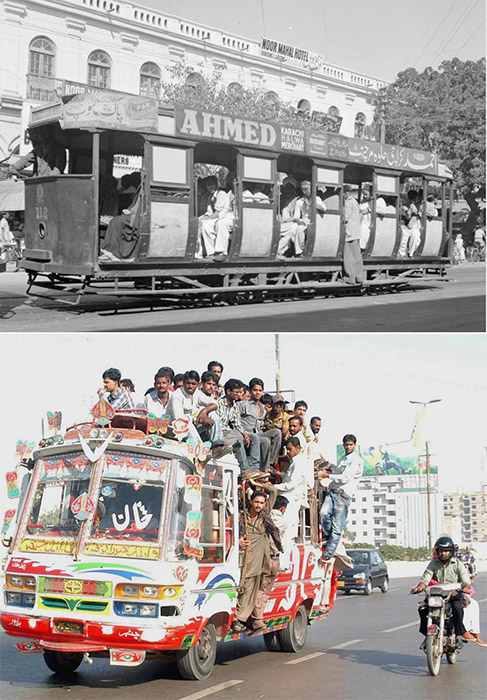

Today, the city has grown to 60 times its size in 1947. This colossal growth has a bearing on the transport sector. Owned by three private sector companies, there were 20 to 50 large buses in Karachi, in 1947. In 1955 the number of tramcars was 157. However, the service was closed down in 1974.

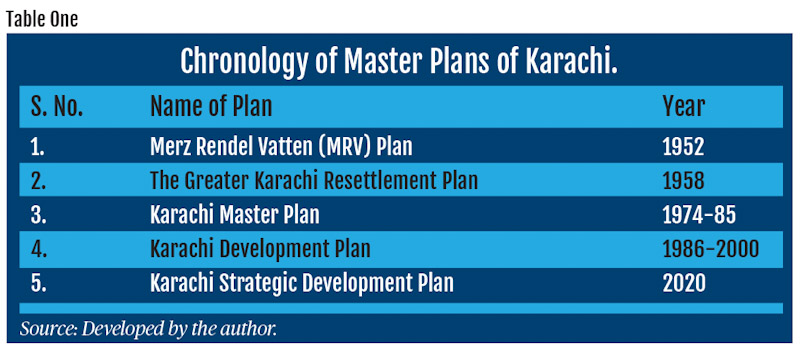

From the year 1951 to 2006, to respond to a fast changing socio-economic scenario, the planners of the city proposed five master plans. Each plan took stock of the existing demand and supply scenario of various sectors through diverse research techniques and made plans for the future by extrapolating the existing requirements. A chronology of the five plans is shown in Table One.

One common thread that cut across all the plans was emphasis (with varying degrees) on the institutional setup for the implementation of recommendations. However, quite a number of times that remained a dream unfulfilled, which in itself could be a subject of investigation for future researchers and urban planning historians.

The Merz Rendel Vatten (MRV) Plan, 1952

Post- independence, it was the first ever plan in the planning history of Karachi. The political climate of Pakistan and its capital (Karachi) were uncertain. The nation was still coping with the grief inflicted by the sudden demise of the Father of the Nation. The new country’s early politicians, religious figures, intellectuals, artists and society as a whole, spent most of their time and energies grappling with various conflicting and vague ideas about Pakistani nationhood. The Objectives Resolution of 1948 was an attempt to resolve this crisis. From a planning perspective, large numbers of incoming refugees brought civic services under pressure. To respond to their needs, the built environment of the city changed rapidly. Some notable developments were the establishment of the University of Karachi, founding of St. Patrick’s College, development of the Nazimabad suburb, Beach Luxury Hotel and the National Museum of Pakistan.

The MRV Plan focuses on a rail system for the provision of commutation services to the dwellers of the city. It proposes a rail-centred and rail-focused bus system, a system of feeder roads, express roads and major roads. To reduce the commutation time and cost, MRV suggests the proximity of residential and commercial centres.

The MRV Plan emphasises the importance of a public transit system and argues that in the presence of a decent and affordable mass transit system, people would not use private vehicles and hence parking problems could also be handled.

The Greater Karachi Resettlement Plan, 1958

Housing-focused, the Greater Karachi Resettlement Plan, 1958 is also called the Doxiadis Plan after the name of a Greek Planning Firm, Doxiadis Associates. The Plan converted a dense city into a sprawl. In addition, it segregates rich and poor areas. The majority of the population was shifted to satellite towns, thus increasing demands on the commutation and hence transport and allied sectors.

The Plan describes the context as “the acquisition of independence which was followed by the great waves of refugees, the outstripping of the feudal stage in the economy as of the distribution of great estates, the break-up of the patriarchal family, the administrative organisation of the State with the new administrative centres which have grown up and the great development schemes are all factors leading to large population movements and to the need for regional planning and more houses and facilities.”

The Plan remains silent on all other aspects of development planning and transport.

The Karachi Development Plan, 1974-85

The Plan, prepared with the assistance of the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), is the most comprehensive out of all the five plans. The preparation on the plan was started in 1968 and it envisaged a rational road network, housing, water supply, transport terminals and warehouses, land management, mass transit and ecological issues.

The political climate was full of challenges. The Eastern Wing of Pakistan was lost and the nation was under trauma. A lot of migrants from former East Pakistan started making Orangi Town their home. Two major educational institutions were pushed to the periphery of the city and close to the Cantonment Area. The nationalisation policies of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto were not going down well with the elites. The decade of the ‘70s is marked by major labour struggles and students’ movements.

Based on the 1985 travel demand forecast, which in turn was based on population, income distribution and local activities, the Plan envisaged a surge in public transport services. It combines the existing rail based transport with the proposed enhanced bus transport services. The Plan has a pro-people commutation consideration and articulates very well the continued operations of multi-modal transport services to low income groups in high-density areas. The Plan is not very encouraging towards private passenger cars as it mentioned that, “Private vehicles providing 44 percent of road passenger miles use 83 percent of passenger road space, while buses providing for 55 percent of road passenger miles use only 17 percent of road passenger space.”

Only road networks were built as proposed in the Plan and that too in a substandard manner. Other components of the plan could not be implemented and nor could the institutional arrangements (KDA) developed for management as stated in the purpose of the Plan.

Karachi Development Plan (KDP), 1986-2000

The KDP had cost the incumbent government Rs. 470 million. Traditional planning skills combined with data based computer modelling techniques generated alternative scenarios for development. The Plan was prepared at a stage when most of Karachi’s civic needs were being taken care of by the informal sector. Monitoring is an essential part of the plan. However, monitoring and information systems, as suggested in the Plan, were not developed and the Plan provisions are being violated. The Plan was made for an estimated population of 10 million to 12 million, which is quite close to the actual figures of the 1998 census (9.8 million). The Plan claims that it has initiated a new planning approach that entails “establishment of a planning process, rather than the production of a conventional comprehensive development plan.” The fictitious assumption of the KDP, vis-à-vis the transport sector, is that the mass transit improvement programme of the Karachi Mass Transit Study would support the future population distribution as proposed by the Plan.

As cited by noted architect and urban planner, Arif Hasan, at the time of making up of the Plan, the political climate was undemocratic, with Army rule and further centralisation (1977-1989). Meanwhile, the emergence of the MQM and the consolidation of ethnic politics resulted in political interference in the implementation of the recommendations of the Plan. The Afghan War and its blowback of guns, drugs and erosion of institutions made governance of the city problematic, followed by political instability and frequent turnover of political setups. A new generation of consumers evolved that has started going more global than local in its cultural and consumerist expressions.

The KDP recommended the building of a bus transit-way network in selected major corridors where the expansion and consolidation of the city was taking place. However, the KDP did not rule out rail based transit, rather it suggested carrying out limited preliminary engineering to protect rights-of-way for possible future rail alignments along Saddar-Tower, from MA Jinnah Road to Lea Market and SITE corridors. The rail system is to be supported by extended bus-centred service and a planned bus network was proposed with provisions for bus depots and 18 terminals. It also proposes to implement the institutional changes and financial arrangements needed to support these programmes. Like its predecessor, the implementation of the KDP remained chequered, and that resulted in more transport issues and the collapse of formal sector transport facilities.

Karachi Strategic Development Plan (KSDP)-2020.

Presented in 2006, the vision of KSDP-2020 for Karachi is, “A world class city and attractive economic centre with a decent life for Karachiites.” It calls for Public Private Partnership to enhance performance of service delivery institutions. The Plan which aims “to set out a strategic framework,” articulated its approach through four objectives: 1) Future Growth of the Metropolitan, 2) Appropriate future housing needs, 3) Infrastructure deficit (to improve on), and 4) Ensure sustainability by establishing institutions and financial paradigms.

The plan mentioned that since 1923, five plans were made for Karachi and they were not fully implemented because of the lack of legal cover to the proposed institutions and policies. Implicit in the claim is the assumption that the legal cover, keeping aside all odds for execution of justice dispensing, would make informality vanish and the demand-supply equation would be equal.

The main critique of the KSDP–2020 is that it bolstered the unbridled for-profit sector for take-over of urban services at the cost of basic planning considerations and principles. The plan is a reflection of the neo-liberal economic mindset, where market takes precedence and basic human rights are commoditised. Its approach is in stark contrast with that taken by the planners and decision makers of KDP, 1974-85. The Plan is written in double dutch with failed attempts to define the meaning, method and impact of those clichés. Some of the phrases of the Plan are reproduced here as quotes. “World class cities,” “investment friendly infrastructure,” “inclusive city,” “harmonious relationship” and “multi-class spaces.”

The Transport sectors’ strategic challenges as identified by the KSDP-2020 are: sustainable mobility; an efficient and safe transport system; a policy, regulatory and delivery framework that places economically efficient solutions, public transport and safety at the forefront. The “developing partners,” as mentioned against those specific challenges in the Plan are: City District Government Karachi Transport Department, federal and provincial governments, funding agencies, communities and civil society, professionals, academics and transporters’ associations.

Karachi’s transport issues cannot be handled in isolation. They have a strong connection with housing (both formal and informal and sprawl versus densification), employment, educational opportunities, land use and health issues. Another important change taking place in Karachi is the presence of more and more women in public spheres, which again has a bearing on the existing transport system. Earlier, this gender imperative was not very evident; hence earlier made plans were not very distinctive about this evolving requirement.

Plans are a response to the political and economic crises of capitalism for the urban built environment. So far it’s a static exercise in which a Master Plan is supposed to be made after every 5 or 10 years. With the exception of KDP 1974-1985, most master plans were out of date by the time that they got published. The problems of Karachi, and transport issues not discounted, are fundamentally social, economic and related to governance. It’s a proven fact that by virtue of its theory and practice, capitalism is insensitive to the poor and yet capital is necessary for the city to survive. How this Arthurian Cycle could accommodate the poor in the circuit of development plans and an independent exercise free from the clutches of political interests, is a question to answer.

The upcoming Master Plan-2030 needs to define the vision of the City. Since 2006, when the KSDP–2020 was first presented, a lot of water has flowed under the bridges of Karachi and those changes need to be understood and articulated for a better vision of the city. The following recommendations might help to plan an economical, timely, efficient and pro-poor transport system for Karachi:

A. An integrated travel and transport Plan, catering to the above mentioned life-defining spheres of urbanities, needs to be made with particular consideration to new evolving realities of spatial growth patterns, environmental compulsions and women in public spheres.

B. Institutional arrangements that could promote and patronise a low cost, reliable, efficient, eco-friendly public transport system.

C. The Plan also needs to define the well capacitated Operation and Maintenance organisations and mechanisms to enable multi-pronged coordination with other civic agencies, the Master Plan department and communities.

D. The upcoming plan also needs to have defined ways of mid-term review of transport and commutation plans to accommodate the changes in travel demands (housing and livelihood opportunities are the two main defining indicators of mode and direction of travel) of the commuting population.

To implement the above-mentioned recommendations, the planning process needs to be autonomous and execution of the Plan free of political interference, manned by well trained and well paid professionals. How to make it possible is another area of investigation for planners and decision makers of the city. The story goes that… “a family of mice has been living in fear because of a cat. One day they come together to discuss possible ideas to defeat the cat. After much discussion, one young mouse gets up to suggest an idea. He suggests that they put a bell around the cat’s neck, so they can hear it when it approaches. All the other mice agree, apart from one wise, old mouse. The old mouse, agrees with the plan in theory, but asks, ‘Who will bell the cat?’” That’s a question that remains to be answered.

PhD scholar, and board member at the Urban Resource Centre (URC), Karachi.