After two years of consecutive low-economic growth — ranging between 1.9 to minus 0.4 percent — Prime Minister Imran Khan appears to have made the right bet on the country’s housing sector to boost economic activity and create new jobs in these times of pandemic.

“Pakistan is adding 4.2 million people annually to its population,” says Zaigham Rizvi, chairman Task Force for the Naya Pakistan Housing Porgramme. “The country needs at least 700,000 new houses every year to match the annual increase in population if average household size is taken at six persons per family,” he told Narratives.

Prime Minister Imran Khan made an electoral promise to provide five million new houses to people belonging to the low-income groups and the Naya Pakistan Housing Programme aims at delivering on this promise. Almost halfway through his five-year term, critics say that the PTI government is unlikely to meet this target. However, the government camp remains optimistic, saying that despite a slow start, the housing programme would prove one of the mainstays in efforts to escalate economic activity in the coming months. Both the public and private sectors plan to launch new projects and complete those in the pipeline at an accelerated pace, from early 2021 onwards.

Zaigham Rizvi says that it was not practically possible for the government to fast track the housing programme. “It took time, because firstly rules and procedures needed to be laid down, then there were the Herculean tasks of identifying state land in 40 cities for the construction of houses, framing banking laws for mortgage financing and involving the private sector in this initiative.”

The Naya Pakistan Housing Programme is the first of its kind in the country, as along with urban centres, it focuses on rural areas, where such schemes have never been launched.

To incorporate new technologies and methods, the government has set up housing research centres in 25 universities that have also been tasked to experiment with new materials in the construction sector

According to the programme’s official website, Pakistan faces an overall housing backlog of 11-12 million units, out of which the urban housing shortage is estimated to be around four million — mostly among the low- and middle-income groups.

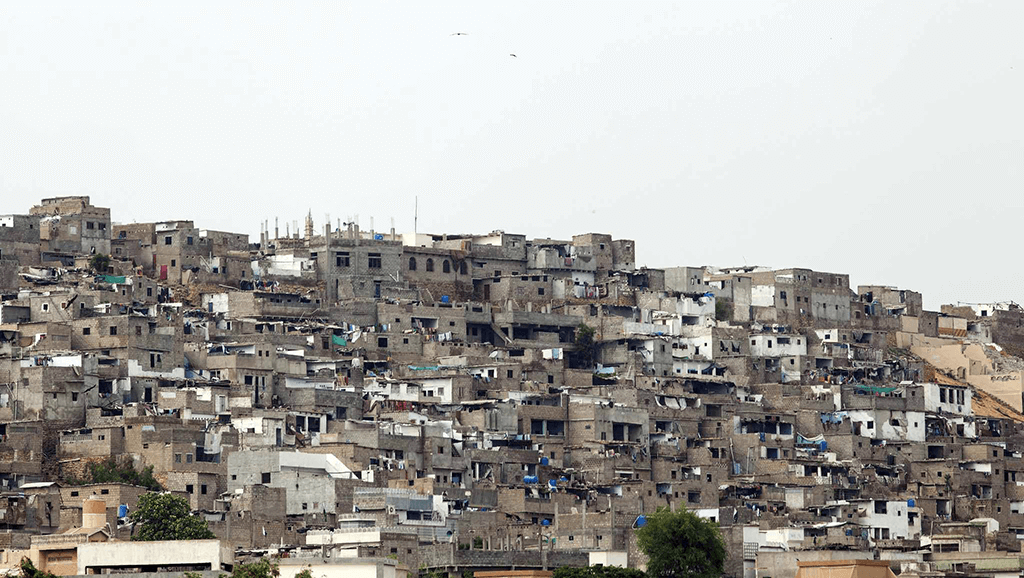

Traditionally, the housing developer sector caters mostly for the middle, upper-middle and rich segments of the population, while the low-income group remains neglected by both the public and private sectors. The result is mushrooming of slums in the urban centres, many of which have been regularised for political reasons or because of public pressure. People living under sub-human conditions in these slums remain bereft of basic amenities, including piped water, a working sewerage system, open spaces, educational institutions and healthcare.

“When we talk of housing in big cities like Karachi and Lahore, it is only about the elite and upper-middle classes,” says Zaigham Rizvi. “Kutchi Abadis (slums) and periphery-urban areas are never included in housing development plans. Now our villages, where 60 percent of the population live, have also turned into slums, as housing problems in the rural areas were never addressed.”

Indeed, the housing sector, despite its money-minting appeal, remains neglected and disorganised, as successive governments despite paying lip-service to the cause never moved beyond mere political rhetoric and slogan mongering. As a result, encroachment mafias filled the vacuum created by the apathy of successive governments. These thugs settled people on encroached lands, forcing people to live in abysmal conditions.

From Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s catchy slogan of “roti, kapara aur makan” (food, clothing and shelter) to Mohammed Khan Junejo’s scheme of “shelter for the shelterless,” from Yousuf Raza Gilani’s announcement of building a million new housing units annually to Nawaz Sharif’s 500,000 housing units per year, there is a long list of broken promises.

Private industry sources say that Imran Khan has shown remarkable determination in pushing through the housing programme, removing one obstacle after another. A construction tycoon, who requested anonymity, said that the prime minister chaired more than 30 meetings to develop the housing programme. “I am a witness to this fact … he held meetings almost every week to materialise this initiative. There were a lot of hurdles. Our bureaucrats, rather than facilitating, seem to focus on how to create obstacles… but Imran Khan took a personal interest in this programme, which will be a game-changer for the economy.”

More than 42 allied industries will get a boost because of construction activity, he added. “Cement and steel sales have already hit record highs… all the other related industries are booming, and we have yet to reach the optimum level of work as the demand for houses outstrips their supply.”

The government plans to construct 400,000 houses in the rural areas, 200,000 in the peri-urban areas and 400,000 in the urban areas annually, starting from 2021.

The official website says that in the peri-urban areas, dominated by slums, the policy would largely use an incremental housing model. “In the peri-urban areas the Policy will develop and improve sewerage systems, water supply, service roads, electricity, and common places/parks for community as well as equipping the habitat/community with basic health and education facilities.”

The government has also involved NGOs to ensure micro financing to the low-income group families to build or buy houses. One example is Akhuwat Foundation.

In the rural areas, where people overwhelmingly live in mud houses — the same way their fathers and forefathers have lived for decades and centuries — the government plans to “launch the scheme of model villages, in which simplicity of rural life immersed in maximum possible facilities of urban life may be provided,” says the official website.

Zaigham Rizvi said that model villages will be built on three to five acres of land with 60 to 70 houses, which will have all amenities including playgrounds. “Children and youngsters are forced to play in fields as there is no concept of open spaces or playgrounds for the community.”

Former administrator Karachi, Fahim Zaman, who actively campaigns against encroachments and advocates people- and environment-friendly development, said that the Naya Pakistan Housing Programme cannot be called ideal, but it has many positives, which will help mitigate the housing problems of the low-income group.

“Slums are expanding in big cities mainly because people do not have an alternate… this initiative will help empower many people of the low-income groups to buy houses as the government is providing low-interest rate loans,” he said. “The poorest of the poor may not benefit from it, but people with small incomes would be able to afford houses… those who pay Rs. 8,000 to Rs. 12,000 monthly rent for small quarters in the slums of big cities like Karachi.”

Zaigham Rizvi said that another big challenge in providing low-cost housing is the use of old construction technologies. “If we want fast paced construction and low-cost housing, then it means we have to be innovative and apply new technologies.”

To incorporate new technologies and methods, the government has set up housing research centres in 25 universities that have also been tasked to experiment with new materials in the construction sector. However, the biggest challenge remains mobilising funds and ensuring housing finance — an area where Pakistan lags behind in terms of mortgage-debt-to-GDP ratio, which hovers around less than one percent. This is the lowest, even by South Asian standards.

The House Building Finance Corporation (HBFC), the only specialised housing finance institution has declined, while the commercial banks’ share in this sector is miniscule. Now the State Bank of Pakistan has been leading the effort through a series of regulatory measures to encourage commercial banks to enter the house financing market in a big way.

The government has also involved NGOs to ensure micro financing to the low-income group families to build or buy houses. One example is that of the “Akhuwat Foundation — the Pakistani version of Bangladesh’s iconic Grameen Bank — which has been taken on board in this scheme. The government has committed a Rs. 5 billion Revolving-Fund for the Foundation, out of which Rs. 3 billion has already been disbursed, against which 7,500 houses have been built and delivered, officials say. The government will give another Rs. 2 billion to the Foundation to build more houses, they said. In micro financing, the recovery rate is almost 100 percent. Poor people may delay loan repayments, but never default, Zaigham Rizvi said.

In Punjab, the Naya Pakistan Housing and Developing Authority (NAPHDA) has been established and its work is gaining momentum, but the second largest province, Sindh, is not owning the programme, he added.

“ABAD (Association of Builders and Developers) is also on board and its members have launched many projects or have projects in the pipeline, which is encouraging,” Zaigham Rizvi says, adding “development projects are now being approved online within 45 days. Earlier this process used to take from six to eight months. “

“What we were not able to do in 70 years, we managed to do in a short span of time, bringing ABAD with its 1000 members in the mainstream, making house financing and getting construction permits quick, easy and transparent and introducing new technologies.”

“In China, a 60-storey building gets completed in a couple of months, using steel structure, columns, and beams, and here, we are still stuck with the old methods. It is time to change, reform and innovate.”

It seems the PTI government has gone to great lengths to push the scheme through and the results should soon be apparent.