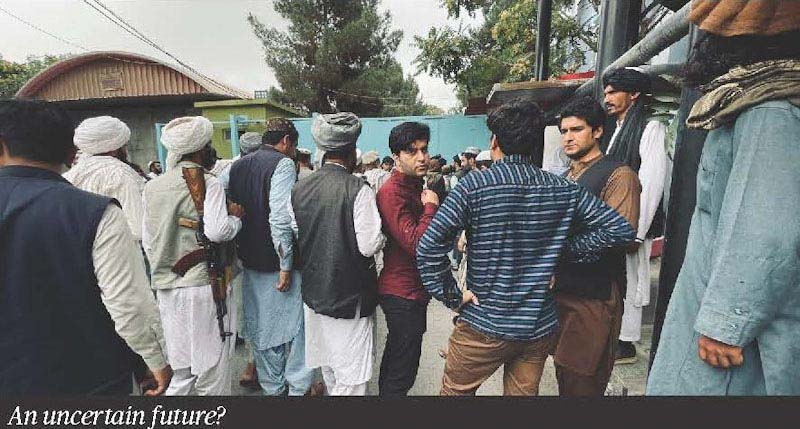

A feeling of uncertainty and an unseen fear descended on my whole being the moment I crossed the narrow steel gate at Torkham border into Afghanistan. Heavily armed men, some barely in their early 20s while others, seasoned grey-bearded jihadists in their 50s and even 60s, holding a whole range of automatic weapons, varying from the infamous Kalashnikovs, machine guns and rocket-propelled grenades to the modern American M4 Carbines and M16s, among other light firearms.

Fortunately, their behaviour was mostly friendly, as one experienced in conversations with a number of Taliban fighters at Torkham and at the security checkpoints — at least six of them on the 228-kilometer journey to Kabul. The armed men at each checkpoint welcomed us with Islamic greetings before asking the driver to open the car boot for checking, most of the time in the presence of the driver. No more than a two-minute stop at each checkpoint made me wonder if this country had really fallen to the Taliban two days ago?

“It is not like the Taliban have no rules to follow. The chain of command is very efficient in tracking down anyone breaking the rules and the violators are immediately identified, tried and punished in accordance with the Sharia Law,” informed Molvi Ahmadullah, my co-passenger in the taxi from Torkham to Kabul, who is expected to be appointed a Taliban mediaperson.

It was Tuesday afternoon, the second day of the Taliban takeover of Torkham, Jalalabad and Kabul. The small roadside markets on the way to Jalalabad presented a deserted look as there were no customers. Jalalabad presented similar scenes as only the general and grocery stores and small businesses were open, but the disenchantment on the faces of the retailers told the story of their day-long wait for customers. My almost five-hour journey to Kabul ended without any bad experience or mishap.

The next day, I met Obaid-ur-Rahman, my Afghan friend on social media for many years. While driving me around different roads of the capital in his car, Rahman started talking about the improved security that he had witnessed over the past three days. “I am not a Taliban fan and I see a dark future for the country under their rule, but the swift reduction in the number of security checkpoints, the softer attitude of the Taliban on the remaining checkpoints, removing blockades from the roads, and the liberty of moving around the city with reduced fear are their earliest achievements,” Rahman told me as we drove past the Iranian embassy on Sher Ali Khan Road, Shahr-e-Nou.

The roundabout ahead that leads to the Sulh Road, where many diplomatic missions are located, was jampacked with men, women and children. Upon inquiring why it was so, the reply of one Hazara family member was, “to leave this hell.” “There is no place for minorities like us in a country ruled by the Taliban. We are trying to get to the UK, but it is unclear if filling these application forms would be enough?” Muhammad Ali Mohsini, an elder from Afghanistan’s minority Shia community, informed me.

At the same roundabout, a Taliban fighter standing next to a US Humvee that the Taliban had captured from the surrendering Afghan National Army (ANA), had a completely different viewpoint. “No one is harming them. It is Ashura-e-Muharram and our elders have given complete freedom and protection to the Shia community and their places of worship,” said the fighter, who introduced himself as Hashmatullah, from Khost province.

After driving through different roads, closed markets and office buildings for about an hour, we arrived at the airport road. The South entrance of the Hamid Karzai International Airport presented the picture of a busy market or festival site. I realised that this was arguably the most sensitive place in the entire country at the moment, with thousands of civilians wanting to enter the airport and dozens of heavily-armed Taliban to stop them from doing so, had gathered in the square, on the roads and the pavements. Sporadic gunshots could be heard every now and then as the Taliban attempted to scare away people who, time and again, tried forcing their way in.

“The rubber pipes are back. The Taliban control crowds by beating people with rubber pipes. Sometimes, they have electric cables that hurt more. But these people will do anything to leave the country, as they don’t have a future here,” Obaid-ur-Rahman added.

I got off the car to take some photographs when a 14-year-old boy selling cakes warned me not to do so. “They will take your phone and smash it,” he said. The boy, Abdul Haq, added that he feared the Taliban might hit him with a pipe too, but he took the risk because business was good; he was selling more homemade cakes at the busy airport surroundings.

The next day, I went to the Taliban Ministry for Peace building to meet Molvi Ahmad, who had invited me over for lunch. The road outside the ministry was packed with dozens of expensive SUVs, and 4-wheelers, and pick-up trucks with machine guns mounted on their roofs. The Taliban on guard searched everyone at least four times, before permitting them inside the ministry compound.

“This was the Ministry of Interior only three days back,” informed Molvi Ahmad as he walked me around several offices before we arrived at his posh office on the third floor. “I have temporarily been given the charge of issuing press releases for one of the top elders. And my colleagues here are responsible for receiving and issuing firearms and ammo to Taliban fighters, who are assigned responsibilities in Kabul’s security setup,” Ahmad added, while pointing to three separate piles of shiny firearms, many of which I hadn’t seen or heard of before.

A young office boy, probably in his mid-20s, brought green-tea and cookies and served it to some 15 persons, including myself, in the office. I could notice the fear in his actions as he moved from one guest to the next. His hands shivered as he gave the cup to an old Talib sitting to my left. I couldn’t talk to him in a room full of people and also due to the language barrier. He spoke Dari, which I barely understood. But Molvi Ahmad was kind enough to accept my request and arranged for us three to sit in a separate room.

“Honestly speaking, I don’t want to come to work here anymore but I need this job to earn food for my widowed mother, my younger siblings and children. Here everyone wants his commands to be obeyed immediately. But I can’t be everywhere all the time and some of these people, like the old man sitting next to you, start harassing me even if there is a little delay,” alleged Barkat Ali (Not his real name, as he requested that I hide his identity), the boy from the Hazara community.

It was reassuring when Molvi Ahmadullah shared his contact number with the young lad and told him to contact him whenever he faced any discrimination. “I am going to request my elders that none of the previous staff of the ministry should be harassed for their ethnic, religious or cultural backgrounds. They are equally important and we need their expertise and assistance in the smooth operation of work here,” Molvi Ahmad assured me.

Later at lunch time, I accompanied Molvi Ahmadullah to the massive conference hall of the ministry, which was full of people, almost all dressed in the traditional white shalwar-kameez, and wearing a black turban or white prayer cap. “This is the third shift. You are seeing more than 600 persons busy having a meal. We have served over a thousand in the past hour. They are coming from every corner of the country to greet the elders on the takeover of Kabul. Go find yourself a place so I can bring you food,” Zakaria, a Taliban who was in charge of provision of food for the guests, told Molvi Ahmadullah.

Over the next three days, most businesses and offices resumed their work. Shops reopened and customers returned; the roads got busy and traffic wardens, dressed in their clean and bright white shirts, black trousers and sergeant’s white caps, worked tirelessly to control the flow of traffic. However, schools, colleges and universities remained closed. Many students were uncertain about their future as the schools were shut down and the ongoing exams were halted.

Many more people were concerned about withdrawing money from their bank accounts as the banks remained closed. Besides the staff’s fears for their personal safety and the safety of the banks’ assets, the main reason was the delay in the Taliban’s announcement of a decisive policy for banking and financial operations.

The opening of schools and the management of financial matters are just two of the many challenges the Taliban will face in the coming weeks and months. For now, their main concern is the restoration of peace, signing of peace agreements with political and military opponents and, above all, convincing the international community and humanitarian organisations to resume their support for a rapidly deteriorating situation that threatens to destabilise Afghanistan.

The writer is a Peshawar-based free-lance journalist, who contributes for leading national and international publications.