Will the post Covid-19 world see more international solidarity to deal with common challenges? Will the world move towards strengthening of multilateralism, which has been under so much stress? The short answer is, this is unlikely if current trends are anything to go by.

Never has the world been so interconnected and yet so atomised. Never has international solidarity been more needed to deal with common problems but unity so elusive. The Covid-19 crisis has thrown these telling paradoxes into sharp relief.

While unprecedented global cooperation and a collective response will be needed to negotiate the many consequences of the pandemic — threats to public health, economic recovery, food security, recession and unemployment — many countries will tend to turn inwards and act on their own. This is what has been happening after the coronavirus struck, with the pandemic only reinforcing a worrying global trend.

The world is, in fact, in the midst of one of history’s most unsettled periods with a number of trends reshaping the international landscape: retreat from multilateralism at a time of multipolarity, the rise of anti-globalisation sentiment, erosion of a rules-based international order, trade and technology wars between big powers and the rise of populist leaders who reject internationalism, pursue hyper-nationalist policies and act unilaterally.

While the UN General Assembly’s 75th session that started in September seeks to reaffirm the collective commitment to multilateralism, this is unlikely to go beyond declaratory statements and sanctimonious speeches.

The retreat from multilateralism has, in fact, emerged as one of the dominant trends in the pre-Covid decade and there is a big question mark over the future of collective global endeavours even at a time of rising multipolarity. There are several factors at play that make the future stability of international affairs uncertain at best and more turbulent at worst.

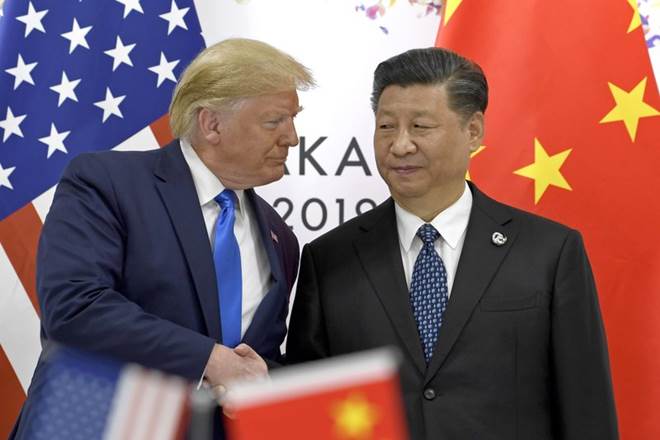

A key factor behind this unpredictability is the renewal of East-West tensions. The confrontation between the two global powers, the US and China — who have the world’s most consequential relationship — underlines how the clash of geopolitical interests and ambitions is contributing to a fraught international environment. The pandemic heightened tensions between them, which were already at a record high before the Covid outbreak with the two countries locked in fierce trade and tech wars. This situation has variously been described as a new Cold War, end of the post-1979 era, and a geopolitical turning point.

An important factor that could shape their future relationship will be the US elections in November, when the next American President will have to decide how to manage relations with China: to stabilise and recast the relationship on new terms, or embark on a course of prolonged confrontation? In both eventualities, a return to engagement that previously characterised relations with China is not expected.

This is because the political and Congressional consensus as well as public opinion that has emerged in the US — fanned by President Donald Trump’s belligerent actions and incendiary rhetoric — sees China as an adversary or enemy that has ‘manipulated’ the US on trade and poses a strategic challenge that needs to be countered and contained, not engaged. Many foreign policy advisers of the Democratic contender for the Presidency, Joe Biden, also happen to be hawks on China. Therefore, whoever wins the election can be expected to follow a tough line on China.

Beijing’s preference is to deescalate tensions and steady relations with Washington. But it is also evident that the Chinese leadership is no longer going to take aggressive actions by the US lying down. It is already pushing back against Western criticism and what it sees as US bullying. There is fresh thinking in Beijing about how to deal with a more antagonistic Washington and growing nationalist sentiment that their country should stand up to US provocations. This sentiment is already driving a more assertive Chinese policy in Asia and beyond.

As for European unity, this has been further tested during the pandemic and with Brexit on even more contentious ground, the future of the European project is ever more uncertain. French President Emmanuel Macron has already been warning of the collapse of the European Union if certain actions are not taken. The role and influence of the EU in international affairs is therefore mired in uncertainty.

Meanwhile, challenges to established international norms and international law continue. It is not just the US that has acted in defiance of multilateral commitments — reneging on the Iran nuclear deal, rejecting the Paris Agreement on climate change, withdrawing from the UN Human Rights Council and the World Health Organisation — but other nations too. Russia by its annexation of Crimea, and in our own neighbourhood, India’s illegal actions in occupied Jammu and Kashmir. Indeed, the most egregious human rights violations continue in occupied Kashmir, with Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government acting in utter violation of UN Security Council resolutions and international humanitarian law.

In fact, right-wing populist leaders such as Modi and Trump have been in the forefront in flouting international rules and acting unilaterally. The rise of such populism, predicated on extreme and intolerant nationalism, has been a major contributory cause for the increasing turbulence and instability of the international system.

A frustrated UN Secretary General, Antonio Guterres has had to frequently remind a fractured global community to respect human rights and international law, and about the value of international cooperation for the common good. In a speech in July, he also drew attention to the “growing manifestations of authoritarianism, including limits on the media, civic space and freedom of expression.” He warned that “Populists, nationalists and others who were already seeking to roll back human rights are finding in the pandemic a pretext for repressive measures unrelated to the disease.” Guterres has repeatedly called for unity and solidarity to address global challenges, often pointing out that multilateralism is needed more than ever to “repair broken trust in a broken world.”

Despite these entreaties before and during the pandemic, international cooperation has remained in short supply. Indeed, weakened commitment to multilateralism continues to be an unedifying feature of the global environment today. From the resurgence of intense geopolitical competition between the big powers, diminishing respect for global rules and go-it-alone strategies of populist leaders, who fan xenophobia for political gain, the picture that emerges is of an increasingly fragmented international system.

This is unlikely to change in the post-pandemic world. It is far from certain what kind of international order will evolve from the present Hobbesian-like melee. The deep divisions between and within countries and a fractured world will make addressing global problems much more formidable in the future. The US Presidential election later this year will be critical for its global impact. Its outcome may not overturn the trends already in evidence, but it could have a major influence on the future of a fraying multilateral system. For now, the outlook for the post-Covid world is not encouraging even at a watershed moment when global cooperation is most needed for the multiple challenges that lie ahead.