Pakistan’s economy is entering 2022 in a vulnerable state. After emerging from the severe balance of payments crisis of 2018 with a period of IMF-led stabilisation, the COVID-19 pandemic combined with the sharp spike in global commodity prices has put renewed pressure on the economy.

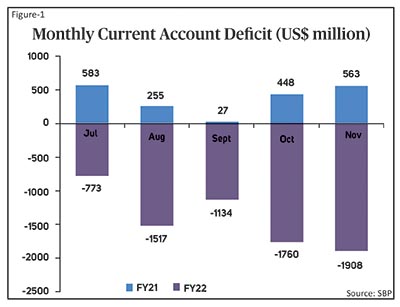

After recording surpluses on the external current account for several months between July 2020 and February 2021, the country has witnessed rising monthly deficits since. While the fiscal year 2020-21, ending June 30th, recorded a moderate overall current account deficit of US$ 1.9 billion (equivalent to 0.6 percent of GDP), the first four months of the current fiscal year has seen the deficit shoot up to US$ 5.1 billion, a swing of almost 500 percent over the same period last year.

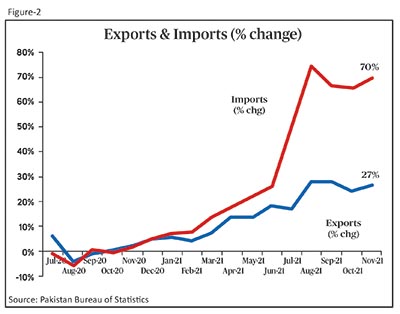

The swing into the red has been driven by the sharp turnaround in the trade deficit. While exports have recorded impressive double digit year-on-year increases each month since last year, led by textiles and apparel, the expansion in exports has been dwarfed by the surge in imports. Import growth in US dollar terms has averaged in the high double digits each month since January 2021, with a cumulative increase of 70 percent in the first five months of 2021-22 (July to November). The import surge has overshadowed the increase in exports by a ratio of 2.6:1, meaning that Pakistan’s exports are financing only 38 percent of the country’s import bill. Figure 1: CAD

As a result, the trade deficit has shot up over 112 percent during July-November compared to the previous year, with foreign exchange reserves held by State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) having declined from a peak of US$ 20 billion in August, to US$ 18.6 billion as of December 10 — despite the US$ 2.7 billion Special Drawing Rights (SDR) allocation and a US$ 3 billion deposit from Saudi Arabia.

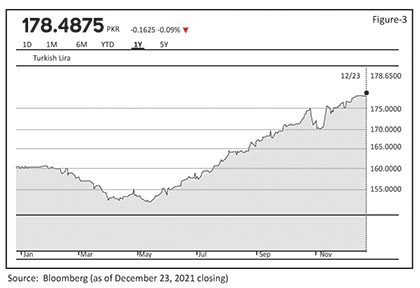

Not surprisingly, the Rupee has slipped 19 percent against the US dollar since the beginning of May, falling from around Rs. 151 per US dollar to Rs. 180 per US dollar in the inter-bank market, cumulatively losing over Rs. 29 against the greenback. In the kerb market, the US dollar has been quoted as high as Rs. 186 for buying, indicating a widening differential with the inter-bank rate that invariably accompanies speculative as well as panic buying. Figure 2: Trade deficit

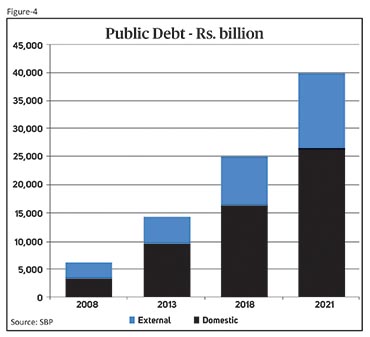

The external account is not the only area where macroeconomic weaknesses have surfaced. The “internal balance” has been completely out of whack for the past three years running, with the fiscal deficit recorded at 7.1 percent of GDP in 2020-21. The average budget deficit for the past three years amounts to 8.1 percent of GDP — the most elevated for nearly three decades.

As a corollary to the persistently large fiscal imbalance, public debt has increased sharply during the past three years, rising 60 percent from its June 30, 2018 level to almost Rs. 41 trillion as of end-September 2021. Figure 3: Pressure on USD/PKR

The large fiscal deficits, among other factors, have also led to inflation being elevated. Headline consumer price inflation has spiked to 11.5 percent year-on-year during November, while averaging 9.3 percent in the first five months of the fiscal year. Food inflation has come in at 11.9 percent in November (urban), and has averaged 10.4 percent between July and November.

With rising food costs accounting for nearly 50 percent or more of the headline Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation during this period, it is clear that non-fiscal and exogenous factors have been at play as well in causing the inflationary spike. Imported inflation via international commodity prices and a falling Rupee were important causative factors as well.

The current episode of a short burst of growth leading once again to an unsustainable gap between imports and exports, underscores the limitations of the flawed go-to growth model Pakistani policymakers have repeatedly chosen. It also points to a long and painful path of structural reforms and institutional overhaul that is needed to turnaround the economy. Figure 4: Public debt

What next?

The rising pressure on the external account and the Rupee has increased uncertainty in the economy, especially with regards to not just where the exchange rate will stabilise against the US dollar, but also about the continuation of the government’s expansionary policy mix.

The uncertainty has been compounded by the fluid developments over the past few months next door in Afghanistan, and the as yet unsettled situation there. The situation in Afghanistan has the potential to either provide a degree of stability on Pakistan’s western border after over forty years of conflict there, or for a period of protracted instability whose effects spill over into Pakistan with regards to internal security as well as the economy. So far, the latter appears to be a more likely outcome given the policy of active and conscious neglect of Afghanistan’s deteriorating humanitarian condition by the international community.

Another factor causing a wobble in the exchange markets is the uncertainty surrounding Pakistan’s return to the fold of the IMF programme. Given the pressure that has emerged in the external account, and which has manifested itself in the weakness of the Rupee, the financial and currency markets are looking closely towards progress, or lack of, in ongoing negotiations with the IMF. A resumption of the Fund programme has become necessary for stabilising the external account, even though it will mean that the government will have to take politically difficult decisions it had avoided when it suspended the programme after the successful reviews in March 2021. With the finance minister signalling his inability to restart the IMF programme on his own terms, it also means that the government will be forced to jettison its growth-oriented policies and reintroduce stabilisation and demand management policies once again.

Whatever the outcome with regards to the IMF programme, a recalibration of the government’s growth policy is required. To cool down the overheating parts of the economy that are driving the surge in imports, headline growth will need to be sacrificed at the margin. To avoid slowing down the entire economy, a more targeted approach that is directed at the consumer and other non-essential sectors, such as cars, mobile phones, durable goods, fast moving consumer goods and other consumer items is required.

Outlook

The global economic outlook, as well as Pakistan’s, is clouded by uncertainty yet again as the new year begins. While international commodity prices have pulled back significantly, as well as somewhat unexpectedly, since hitting near-term peaks in October, volatility in the markets has remained high. The rapid spread of the Omicron variant of the novel Coronavirus has cast a shadow on the prospects for the global economy.

Other grey spots for the world have come from China’s intensifying economic slowdown, despite following a fairly successful Zero-Covid strategy during 2021. The latest Caixin Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) has declined into negative territory (below a reading of 50), indicating contractionary conditions in the manufacturing sector. China’s economy has been buffeted by high-profile bankruptcies of systemically-large real estate developers like Evergrande, an energy shortage, and is facing growing headwinds due to muted policy stimulus, unlike other large economies like the US and EU.

At the same time, the global supply chain disruption is likely to take several months to ease, causing inflation to remain elevated well beyond the pain threshold of most central banks. The US Federal Reserve has led the change in tone of central banks around the world by altering its read of inflation from “transitory” to “uncomfortably high” and thus requiring immediate attention. The US Fed has not only signalled the end of its bond purchase programme, but also three moderate interest rate increases in 2022.

All of the foregoing developments have consequences for Pakistan. A slowdown in the world economy, depending on how protracted and widespread it is, can affect exports as well as remittances. A rising interest rate environment in the US will almost certainly reduce availability of capital for emerging markets, while increasing the cost. With an elevated external financing requirement, this aspect could hurt Pakistan’s ability to tap into global capital markets.

However, the most consequential of the developments for Pakistan’s economy will be the direction of movement of international commodity prices. While commodity prices have been buffeted by contrarian developments in recent weeks, especially in the oil markets, the most likely trend in the near term appears to be downward. This would mean that Pakistan is offered significant respite by a cooling down in the overheated commodity markets.

If this positive development were indeed to play out, then inflation can be expected to begin easing moderately after a few months. The inflationary outlook is hinged almost entirely on the outturn in international commodity prices, as well as the strength and timing of government efforts to dampen the overheating in the economy. One negative factor that will keep a floor under the downside for inflation, however, will be the need for the government to collect petroleum taxes and levies under the IMF programme. This will limit the pass-through of a fall in international commodity prices, and ensure higher-than-otherwise interest rates.

While headline GDP growth for 2021-22 may exceed the government’s expectations on the back of bumper crops, the momentum in economic activity is almost certainly going to decelerate as the year progresses, with the policy stimulus in place since 2020 being replaced with anti-growth austerity measures, and elevated interest rates.

A quick return to the fold of the stalled IMF programme, with all its negative ramifications for the economy overall, will provide a measure of stability to the external account and the Rupee. On the other hand, if the IMF chooses to haul Pakistan over the coals for whatever reason (geopolitics or technical), then the external account, as well as the Rupee, are likely to face a period of instability.

In sum, will Pakistan’s economy achieve a “hard landing” or a soft one in 2022 remains an open question for now, but the balance of risks appears to place it somewhere in between at the start of another year.

The writer is a former member of the Prime Minister’s economic advisory council and heads Macro Economic Insights (Pvt.) Ltd. a consultancy based in Islamabad.