Aesop’s fable 87 bears an astonishing resemblance to Karachi and, by extension, Sindh. The goose that laid one golden egg everyday was quite well-kept for being the source of her master’s riches, until greed killed it.

Being the proverbial golden goose, what ails Karachi ultimately ails the entire country. Democracy worldwide is under threat from political authoritarianism, and the case of Sindh falls right within this ambit. The pre-national election year in Sindh is especially a tumultuous time; 2022 will be no different. In fact, the ruling Pakistan People’s Party is making sure the new year brings with it more chaos than usual; the party does, after all, have a history of benefitting from disorder.

The Local Government (Amendment) Bill 2021 bulldozed through the Sindh Assembly threatens to do just that. Protests and petitions to undo the extremely controversial and totalitarian Amendment will be the defining concern of 2022. Instead of devolving powers to local bodies as agreed upon in the 18th Amendment, the new bill snatches away what little authority was left with the municipalities after the PPP rolled back the Musharraf-era local bodies system by introducing the Sindh Local Government Act 2013.

The Sindh government is under pressure from the Supreme Court to hold the local bodies’ elections. But it does not want to; with nothing to show for in the last 13 years, the party in power knows that if elections are held its performance will belie all its political claims to the throne of urban Sindh.

Essentially, the amended LG Bill 2021 leaves local bodies and the population of Sindh without any recourse to problems. Behind this undemocratic move is just plain old greed for power and money. The PPP is simply unwilling to devolve administrative and financial authority to the locally elected functionaries. In essence, it is trying to feudalise urban Sindh.

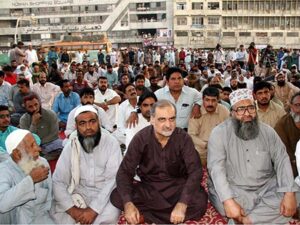

The entire political opposition in Sindh is unanimous in its condemnation of the amended bill. The year 2022 will see a string of street protests, joint or otherwise. Petitions have already been filed in court on the plea that this bill violates the very letter and spirit of the Constitution. While it is true that the PPP cannot be alone held responsible for the dismal state of affairs in a city the size of Karachi, the lopsided distribution of electoral seats in rural and urban Sindh is single-handedly responsible for the current misrepresentation in the cities of Sindh.

Sindh’s scattered opposition has thus far shown no interest in working together for the city or the province. And why should they, when most parties on the opposition bench get a better share of the pie by remaining on the sidelines. Also, the last 13 years of PPP rule plus the highly criticised 2017 census have seen such dramatic and forced demographic changes in urban Sindh, that the new, emerging reality has pushed the old guard out of its political depth.

It is said that Karachi is a city where it is easier to make a fortune than to earn an honest living. That speaks volumes about its politics and economy. 2022 will witness the kind of political wheeling and dealing that comes at the back of a major development. The Sindh Local Bodies Bill 2021 may, for now, be just a smokescreen to avoid holding municipal elections, but it will cast a long shadow in and beyond 2022. And on the off chance that it does manage to get implemented, the altered urban dynamics will further deepen ethnic rifts and political hostility.

Under the chairmanship of Asif Ali Zardari, the PPP has remained singularly focused on power consolidation and if it continues to play its cards the way it has until now, the party hopes to once again see an expansion in its influence beyond provincial boundaries in 2022. Despite losing Lahore’s NA-133 constituency to the PML-N in the December 5, 2021 re-election, the party believes that its significantly improved performance is an indicator of the PPP’s resurgence in Punjab. But that’s not all.

Frustrated with Imran Khan and his Tehreek-e-Insaf, the establishment seems to be facing an acute shortage of viable alternatives. Already facing political resistance in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan, the corridors of power would not want to open another front in Sindh. And so given the PPP’s proclivity for power at the cost of governance, reports of a rapprochement with the establishment are not entirely beyond belief.

No longer willing to bet on a single player in Sindh or in the Centre, the establishment seems more keen to hedge its bets by employing multiple strategies; one of them is to keep the Muttahida Qaumi Movement and Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf placated in their struggle against the People’s Party in urban Sindh. There are, however, two political parties that cannot be underestimated: Mustafa Kamal’s Pak Sarzameen Party and the Jamaat-e-Islami Karachi with its Amir, Hafiz Naeem ur Rehman. Both have public appeal and both appear all set to fight the long fight against the PPP.

In any case, the powers that be have until the beginning of 2023 to decide if they want to back the People’s Party for both Sindh and Centre or try out a new hybrid arrangement.

The Grand Democratic Alliance (GDA), formed in 2017 to defeat the PPP in the 2018 general elections, has proved to be just as ineffective as the political parties that make up the alliance. The GDA could hardly dent the PPP vote bank in 2018, despite seat adjustments with the PTI, and even now it is proving to be obsolete.

It is not just urban Sindh that is groaning under the pressure of corruption and power abuse, rural Sindh is faring far worse. Despite deprivation and deterioration across vast swathes of Sindh, the party in power continues to wield political influence in the countryside and remains firmly entrenched. The old PPP guard, as well as veteran Sindhi nationalists, have all but faded away. Their young successors don’t share the same ideological passion. So, not only will the GDA not be a dependable factor in 2022, rural support for the PPP will carry the party forward beyond provincial boundaries.

What the PPP wants for itself from the Centre has always been diametrically opposite what the latter is willing to give to Sindh. This problem will persist throughout 2022. The party alleges that the ruling PTI has delineated constituencies across Punjab to suit itself. Unfortunately, the same holds true for the PPP in urban Sindh, especially Karachi.

But that is not going to stop Asif Ali Zardari and Bilawal Bhutto Zardari from trying to make their way towards Islamabad. The tabdeeli (change) that People’s Party demands in the Centre is not what it is willing to allow on its own turf. As a result, the year ahead will see the party run two separate election campaigns: one on the home front and the other in Punjab.

Unfortunately, there’s a clear lack of vision among the political aristocrats of Sindh, which is quite natural given that aristocracy by its very nature tends to be self-absorbed. That is not going to change on its own or anytime soon. However, the free flow of information assured by technological advances is forcing a paradigm shift. Corruption and power abuse are no longer being left unchallenged, and the feudal rulers of Sindh are slowly but surely under pressure to bow to optics and accountability.

The PPP had hoped that forced demographic changes in urban Sindh would dilute the opposition. It has worked in the short term, but nowhere in history has this proven to be a sustainable strategy. Despite its diverse ethnic makeup, Karachi and by extension urban Sindh is waking up to the realisation that if nothing changes, the city will collapse under the weight of misgovernance.

The writer is a senior journalist and an Earth Rights campaigner.