After experiencing a sharp, but short, burst of frenetic economic activity lasting a few months, the economy appears to be back in familiar territory – skating on thin ice. Macroeconomic imbalances are growing, with the vulnerabilities most evident with regard to the country’s perennial Achilles heel, the external account.

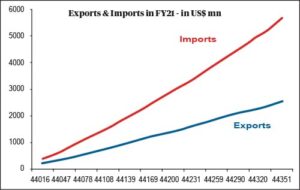

Import growth has accelerated to an astounding 74 percent in US dollar terms for the first two months of the current fiscal year (July-August), compared to the corresponding period last year, with imports topping US$ 12 billion. While exports have also recorded an impressive gain of around 28 percent, the spike in imports outstrips the rise in export earnings by a factor of nearly 3:1. More worryingly, exports in the first two months of the fiscal year are paying for only 37 percent of the country’s total import bill, down from levels of around 50 percent in periods of relative stability.

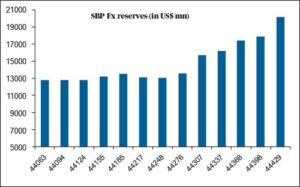

The external trade deficit has ballooned as a result, to US$ 7.6 billion in two months, depicting an increase of 123 percent over the same period last year. Driven largely by the momentum in imports, the external current account is accumulating an ever-larger deficit, after several months of being in surplus. Despite these adverse developments, the central bank has still managed to accumulate foreign exchange reserves, taking them to US$ 20 billion as of September 10, the highest level in Pakistan’s history.

The country’s forex reserves have not whittled down to pay for the rising external current account deficit. This is largely on account of the US$ 2.7 billion received from the IMF in August as part of the international lender of last resort’s global allocation of Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) to its members. However, without fresh capital/financing inflows, SBP’s forex reserves can easily come under pressure in the next few months if imports are not dampened.

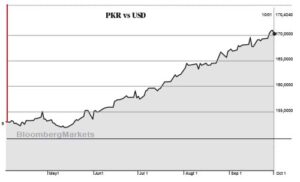

Nonetheless, the widening current account deficit amid muted financing inflows, other than the one-time SDRs allocation, has meant that the Pak Rupee has been under growing pressure over the past few months. Since the beginning of May, the rupee has slid from around 150 per US dollar to 169 per US dollar in the inter-bank market, cumulatively losing Rs 11 or 12 percent against the greenback.

Till recently, the government was of the view that the import surge was largely on account of one-off imports (such as coronavirus vaccines), elevated international commodity prices, and a reflection of strong domestic economic activity – implying both that the surge was temporary as well as a ‘good’ thing for the economy.

However, even a cursory examination suggests that the accommodative policy mix in place is encouraging, as in the past, a substantial quantum of “non-essential” imports such as cars, mobile phones, luxury goods and foreign consumer goods. The policy framework is too accommodative of imports. Apart from the overall stimulative fiscal stance, negative real interest rates, a sizeable cash injection by SBP, lower import duties, and targeted fiscal incentives for construction as well as the auto sectors, are all encouraging consumer goods imports. In an effort to combat inflation, SBP guided the rupee to a range of around Rs 150-153/US$ for some months earlier this year, where the local currency was slightly overvalued – another factor which encourages imports.

In addition, the government is considering incentivising more lending to the private sector by commercial banks by taxing lenders with “low” advances-to-deposits (ADR) ratios. In short, fiscal, monetary, commercial as well as exchange rate policy have all been aligned for the past many months to promote the government’s “growth push.”

After being compelled to pursue stabilisation and anti-growth policies to combat the 2018 balance of payments crisis, which resulted in loss of political capital of the government, culminating in a string of bye-election defeats, the desperation to switch to pro-growth policies well in advance of the next general elections due in 2023, is both palpable as well as understandable.

Nonetheless, choosing the same deeply-flawed growth model that has pushed Pakistan into economic crisis time and again since the early 2000s is incomprehensible. Rather than show some imagination, and selectivity, in the choice of growth drivers, the PTI government has gone for the same debt-financed, import-dependent consumption binge that has repeatedly led to boom-bust cycles since the 1990s.

Due to two structural factors, Pakistan suffers from an acute balance of payments constraint.

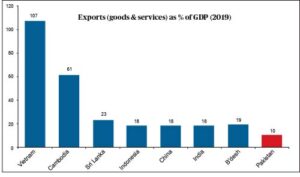

The first is the small, and narrow, export base. Total exports (goods as well as services) account for only 10 percent of Pakistan’s economy, the lowest share of GDP for any peer country. By comparison, the relative size of India’s export sector in 2019 was over 18 percent of its economy, Sri Lanka’s exports were 23 percent of GDP (the highest in South Asia), while Bangladesh’s amounted to 15 percent of GDP. Vietnam’s export sector occupies a whopping 107 percent of its economy, reflecting the outsized external orientation of its economy.

The second structural problem that hobbles Pakistan’s external sector is the economy’s dependence on imports. The country imports energy, food (despite having a large agrarian economy), raw materials, machinery as well as consumer goods. Imports amount to nearly 19 percent of GDP, more than double the share of merchandise exports. Hence, there is a large – and growing – underlying structural trade deficit.

As a result, it is estimated by the Asian Development Bank that the balance of payments constraint kicks in every time the economy grows around 3.8 percent or higher for more than a few years. Simply put, it means that Pakistan runs into balance of payments difficulty at fairly low rates of GDP growth.

The current episode of a short burst of growth leading once again to an unsustainable gap between imports and exports, underscores the limitations of not just the flawed go-to growth model Pakistani policymakers have repeatedly chosen, but the capacity limitations of Pakistan’s policymakers itself who have been unable to recognise the constraint as well as work around it.

Despite the gathering of storm clouds on the horizon for the economy, however, the government can lay claim to some successes over the past one year. There has been over-performance in 2020-21 with regards to growth despite the very challenging context, the handling of the Covid-19 pandemic has largely been deft and proactive on the whole, performance on tax collection has been above-expectations, there has been a significant reduction in the accumulation of power sector circular debt – and the country has delivered a stellar performance on its FATF obligations in a short space of time. Public debt is also on a declining path as percent of GDP, a key objective of fiscal consolidation. Hence, the government can argue it has ticked many boxes.

Despite these successes, however, progress on many fronts in terms of structural reforms remains elusive, and the government’s underwhelming economic management has been responsible for the rising imbalances and vulnerabilities.

In addition, the external account is not the only area where macroeconomic weaknesses are becoming ever apparent. The “internal balance” is completely out of whack for the third year running, with the fiscal deficit recorded at 7.1 percent of GDP in 2020-21. The average budget deficit for the past three years amounts to 8.1 percent of GDP – the most elevated for nearly three decades. More reflective of the underlying fiscal stance is the primary budget balance, as it excludes interest payments, which now make up the bulk of government expenditure. The primary balance for 2020-21 was recorded at a deficit of 1.4 percent of GDP. For the ongoing fiscal year 2021-22, the primary balance is projected be in deficit to the tune of around 1.6 percent of GDP – compared to the target of a surplus of 0.4 percent of GDP agreed with the IMF in March this year.

As a corollary to the large fiscal imbalance, inflation has remained elevated. Headline consumer price inflation has averaged 8.8 percent over the past three years, with food inflation a leading driver. Food inflation has averaged 11.3 percent during the tenure of the PTI government, and has accounted for nearly 50 percent or more of the headline CPI inflation during this period; indicating that non-fiscal and exogenous factors have been at play as well.

What next?

The rising pressure on the external account and the rupee has increased uncertainty in the economy especially with regards to not just where the exchange rate will stabilise against the US dollar, but also about the continuation of the government’s expansionary policy mix.

The uncertainty has been compounded by the fluid developments over the past few months next door in Afghanistan, and the as yet unsettled situation there. The situation in Afghanistan has the potential to either provide a degree of stability on Pakistan’s western border after over forty years of conflict there, or for a period of protracted instability whose effects spill over into Pakistan with regards to internal security as well as the economy.

Another factor causing a wobble in the exchange markets is the uncertainty surrounding Pakistan’s return to the fold of the IMF programme. Given the pressure that has emerged in the external account, and which has manifested itself in the weakness of the rupee, the financial and currency markets will look closely towards progress, or lack of, in the upcoming talks with the IMF. A resumption of the Fund programme has become necessary for stabilising the external account, even though it will mean that the government will have to take the politicallydifficult decisions it had avoided when it suspended the programme after the successful reviews in March. If the finance minister is unable to restart the IMF programme on his own terms, it will also mean that the government will have to jettison its growth-oriented policies and reintroduce stabilisation and demand management policies once again.

Whatever the outcome of the talks with the IMF, a re-calibration of the government’s growth policy is required. To cool down the overheating parts of the economy that are driving the surge in imports, headline growth will need to be sacrificed at the margin. To avoid slowing down the entire economy, a more targeted approach that is directed at the consumer and other non-essential sectors, such as cars, mobile phones, durable goods, fast-moving consumer goods and other consumer items, is required.

Apart from tightening of fiscal and monetary policies, more direct measures are also needed. At the time of writing it appears that a belated recognition of the severity, as well as urgency, of the balance of payments problem has begun to dawn on the government. The finance minister has talked about the need for introduction of regulatory duties on non-essential imports, cash margins and other elements of commercial policy.

Outlook

The outlook for the economy over the next two years appears non-benign, unfortunately, even if the re-engagement with the IMF proves successful. There appear to be quite a few hoops of fire ahead for the global economy that are likely to impact Pakistan. The inflationary outlook is worrisome, especially with the oil market displaying signs of extreme tightness and excess demand down the road, according to an analysis by Bloomberg. Coupled with the already-elevated international commodity prices, this could herald a period of sustained price pressure ahead in the economy.

At the same time, growth is likely to cool below the government’s current expectation. This combination of rising inflation and slowing economic growth is going to prove discomforting for the government in the run up to the 2023 general elections.

The silver lining is that if a meaningful course correction in the government’s economic management is implemented, a balance of payments crisis not too far down the road can be averted. While a moderate uptick in headline growth under the BoP constraint imparts uncertain benefits at significant cost to large parts of the population, the avoidance of yet another economic crisis will save millions of Pakistanis from further misery of living under protracted stabilisation policy. The choice is bleak but necessary in the short run.

The writer is a former member of the Prime Minister’s economic advisory council and heads Macro Economic Insights (Pvt.) Ltd. a consultancy based in Islamabad.