An individual human life is not one-dimensional. When individuals are grouped into communities and become part of a larger nationhood, it becomes manifold complex. This complexity is further thickened when a new nation is born on an idea and does not have historical roots as a single nation per se.

Pakistan falls into the category of those few countries in the world where an idea preceded the birth of the nation. The struggle for Pakistan, which spans almost a century, passed through many phases, including demands of basic rights as a minority in a Hindu-dominated British India to achieve a separate homeland in the culminating stage of this Herculean struggle. Since its independence, Pakistan has followed a peculiar path as a nation and an in-depth understanding of this continuity with a psycho-social analysis is a prerequisite for moving further on the path of strengthened nationhood.

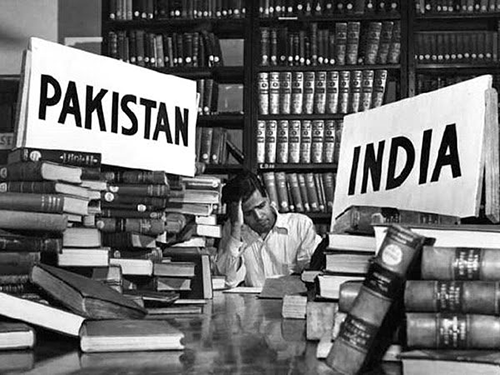

Birth of a Nation

Till in 1857 when the British finally took over the reins of power, Muslims had been ruling the subcontinent for over 700 years. However, during this period, Muslims as a ruling elite settled in various parts of the subcontinent — Hindustan of those times – remained without any conscious effort to form a nation. After the death of Mughal King Aurangzeb in 1707, and subsequent militant rise of Hindus and Sikhs, Muslims did invite foreign Muslim rulers to support them in the power struggle, yet this struggle was aimed at ruling the entire subcontinent and not forming a separate country.

It was in the aftermath of War of Independence in 1857 (called mutiny by the British) that Muslims saw a quick ascendance of Hindus as a community that they felt compelled to protect their rights within the framework of an equal, yet distinct citizenry. When the leadership of the Indian National Congress took a biased stance on Bengal’s Partition in 1905, Muslims formed their own political party to present their case effectively to the government.

Gradually when the Hindu-dominated-Congress demanded for independence and asked the British to Quit India, Muslims feared that in a new country working on western style democracy, they would be overwhelmed by the majority. This gradually led to the demand for a separate country for the Muslims on the basis of religion from asking for political rights like separate electorate and more representation at every level – from the Parliament to the government jobs.

This religious distinctness from Hindus served as a founding pillar of the ‘Two Nations Theory.’ The Muslims in India nurtured this thought for many years. However, after Independence they had to adjust according to the emerging realities. Principally on the basis of the ‘Two Nations Theory’ and Pakistan as a separate homeland for the Muslims, all Muslims living in India should have been allowed to migrate to Pakistan. But it was not followed with a plea that a Muslim Pakistan will be a deterrent guarantee to safeguard the interests of Muslims living in Hindustan. Since Pakistan was found on the golden universal ideals of Islam, it was assumed that a fair and equal treatment to the minorities in Pakistan will set an example for Hindu-India to treat its Muslim minority fairly.

While majority of Muslims in India were politically committed to achieve a separate homeland, two distinct groups within the Muslim community opposed the birth of a new country. The clergy opposed Pakistan as they, without taking into account the ground realities, dreamed of ruling a united India. The other group comprised those nationalists and ethnic leaders who were affiliated to the Indian National Congress for various reasons. After the creation of Pakistan, clergy took it as an opportunity to transform the new country according to their version of a religious state, which somehow did not sanctify equal rights of the minorities. The acrimonious debate on separate or joint-electorate for the minorities did not help build a nationhood. The clergy till now is less focused on social, political and economic issues of a modern nation state and its citizens, and often bogs down the government and people on their transnational and extra-territorial ideals. The other group that comprised the Indian nationalists and ethnic sub-nationalism took the new country as a fait accompli, but created a lot of hindrance in promoting Pakistani nationalism. Often their demands for provincial autonomy vis-à-vis a strong center varied from a weak federation to confederation to secession. The politics in the first decade after creation of Pakistan faced this challenge of fully autonomous provinces leaving only defence, foreign affairs and currency to the center to the extent that it took nine years to formulate the first constitution.

In the last 75 years, one factor has been established that the federation of Pakistan has always reverted to democratic practices, and now the need of time is to reinforce it with suitable changes to make it efficiently functional

These two divergent groups prevented strengthening of nationhood after the Partition of India in 1947.

Pakistan was a new country and a nation comprising two distinct regions: one in south-eastern part of the subcontinent as a homogeneous community of Bengali ethnicity and the other, a conglomeration of four distinct ethnicities in north-western region. This new country and nation also faced two foreign opponents right from the beginning: India and Afghanistan.

Since the Indian National Congress had enjoyed a lead in the demand for an independent country and overthrowing British rule, it had already nurtured a nationhood dominated by Hindu majority. This Hindu-dominated Indian nationalism had not only opposed the creation of Pakistan, but later made it an agenda to nullify the partition to materialize the dream of Akhand Baharat. Afghanistan had also existed as a nation since 1747 in some form and had ceded various areas to the British that now formed part of the newly born state of Pakistan. Afghanistan caused many irritants when Pakistan started consolidating its nationhood (disturbances in the princely state of Dir on the issue of complete accession to Pakistan is one such example, and the subsequent fanning of the Pakhtunistan issue). This malaise which started just after the creation of Pakistan continued in some form even till now. Following the adage of enemy of your enemy is your friend, both Hindustan and Afghanistan either collaborated or potentially presented not only a two front scenario but also caused, aided and abetted ethnic schism to Pakistani nationhood.

Notwithstanding the need for genuine provincial autonomy under the 1973 Constitution, the growls for more autonomy and the alleged exploitation by the center continue even today. The Pakistani nationhood has to wink or close the eyes from this schism in good faith, yet one cannot completely ignore the presence of such elements whose demands for more autonomy have a hidden malaise than a genuine concern for the poor masses.

So, in nutshell after the creation of Pakistan due to its peculiar background, the country faced internal challenges which were both ideological and political, and which never allowed the state and society to chart a clear path of nationhood that converges to an efficient modern functional state.

Treading the Difficult Path

After Independence, Hindustan emerged as a homogeneous state as it did not face any Hindu group to challenge its foundations. The Muslims that were left behind in Hindustan and had fully supported creation of Pakistan, soon adjusted themselves to the new state. One result of this homogeneity was early formulation of the Indian constitution in which Hindustan was to function as a federation with a strong center but fairly autonomous provincial states. Contrary to this, a part of Bengali top leadership had already proclaimed views like Sovereign United Bengal when it became apparent on Partition that Bengal would be divided in two parts.

The former chief minister of Bengal preferred to stay in West Bengal for some time and even initially did not accept Pakistani citizenship. This resulted in internal division of the only political party which had created the new country. When Quaid-e-Azam Mohammed Ali Jinnah visited East Bengal in 1948 and declared Urdu as a national language, the signs of provincial schism became visible in support of Bengali language. Notwithstanding that Bangla was language of a majority province, but still it was language of a province, and Pakistan had four more provinces (merging all four provinces into One Unit took place much later in 1954 when these provinces were jointly called West Pakistan, and East Bengal province was called East Pakistan), which could also claim equal language rights if same were given to East Bengal.

In Hindustan, contrary to this, now the state demanded for a state language to be adopted as equal to Hindi language. In the same vein, when the Pakistani Constituent Assembly started drafting the Constitution, it faced the power issues on provincial grounds keeping in view of a clear majority of East Bengal vis-à-vis all four western provinces. Resultantly, the principle of ‘parity’ was introduced which at best can be termed as a politically expedient tool but surely not in line with best practices of majority-led western democracy by a nation that had chosen it as a system of government.

In these post-independence early years of internal power bickering, Pakistani nationhood developed a political culture where most provincial leaders were asking for maximum autonomy, whereas the ruling party was trying to carve a strong center that could transform this heterogeneous country into one nation that had to survive facing rivalry of its two immediate neighbors Hindustan and Afghanistan.

In the harsh political squabbles when an opponent showed any affinity with any of these two rival countries, or asked for more autonomy, the terms like ‘ghadar’ (traitor) came into use with impunity. Today, when we condemn this trend and mostly blame state agencies for this negative assertion, we often forget that this political culture was nurtured by the politicians during the early years of Pakistan. Two stalwart politicians from East Bengal – Hussain Shaheed Suhrawardy and Moulvi AK Fazlul Haq — had to face such allegations, but ironically, they also were responsible for a fog which led to this.

Two passages which are part of book ‘Party Politics in Pakistan: 1947-1958’ by KK Aziz throw light on the issue. He writes on page 94: “When in June 1947 the Viceroy of India announced the scheme under which the province of Bengal was to be divided between Pakistan and India, HS Suhrawardy started a campaign for an ‘undivided sovereign Bengal’. Coming from an old Muslim Leaguer and a former Chief Minister of Bengal, this idea of an Independent Bengal was not palatable to the All-India Muslim League which had fought for and achieved a partition of the country. From this incident may be traced the Muslim League-Suhrawardy difference of opinion. The Muslim League took the first step in replacing him with Khwaja Nazimuddin as leader for the Bengal Muslim League. On his part Suhrawardy made the rift irrevocable by staying on in India, professedly to look after and comfort the Muslims left in India; later it was alleged by his political opponents that he had done so because he had no confidence in Pakistan’s survival as an independent country. He came to Karachi in December 1947 to attend the Muslim League annual session, and protested against the rule that residence in Pakistan should be a requirement for membership of the Constituent Assembly. But his seat in the Assembly was declared vacant on the ground that he had never attended any session and was residing in a foreign country”.

One can just imagine the charged environment in December 1947 when India had already forcibly occupied the State of Junagadh in November and had attacked Kashmir in October and war was still ongoing.

Moulvi AK Fazalul Haq also came under the same fog of suspicion and fervor of patriotism when he was charged for anti-Pakistan statements during his visit to Hindustan in May 1954 as Chief Minister of East Bengal. It is also interesting to note that he became chief minister as a result of 1954 elections in Bengal in which the United Front had defeated the East Bengal Muslim League. It will also be of great instructive value for the student of history if they study the original 21-point manifesto of the United Front which demanded maximum provincial autonomy, including abolition of visa between Indian Bengal/Hindustan and East Bengal (Dawn, 20 December, 1953 as quoted by KK. Aziz in his above referred book on page 104).

On page 19 of his book, KK Aziz writes: “After his return [Karachi visit in May 1954] to Dacca, Haq visited Calcutta, the capital of Indian Bengal, and there indulged in some alarming utterances. At one reception he said that he hoped, with the help of people of India, to remove the artificial barriers between the two Bengals; on another occasion he declared that he did not believe in the political division of a country and was not familiar with the ‘two new words’, Pakistan and Hindustan”. Though when asked by the then Prime Minister of Pakistan Mohammad Ali Bogra, who himself was a Bengali, Haq retracted and denied any such statement. However, as KK Aziz writes on the same page, “But more was to come. On 23 May the New York Times published an interview with Haq by its Karachi correspondent, in which he was reported to have said independence of East Pakistan would be the first thing that his ministry would take up”. Haq again refused, but “When the Prime Minister confronted him with the correspondent who had interviewed him and the Reuters’ representative who had accompanied the correspondent, both the journalists stuck to their story…. It was on the basis of Haq’s Calcutta speeches and his interview with the American paper that the Prime Minister described him as a traitor to his country and to his province.”

Pakistan started its journey with almost a zero account as a nation but today we are a nuclear power, being counted in the top 10 military powers of the world, GDP growth ranks in the first 30 countries, our cities are thriving, and literacy rate for both genders has improved

When all this was done between East Bengal and the Center, all was not amicable on the western portion of the country. Pakhtunistan issue was smoldering in erstwhile NWFP, Sindhi sub-nationalism also was demanding complete autonomy, and the princely state of Kalat was also becoming militant instead of voluntary assimilation to Pakistan; and there were irrefutable evidences that government in Afghanistan was continuously feeding this fire with some collusion of Hindustan.

From those days onwards Pakistan continuously suffered from the unending internal schism on political nature of the state, and its center versus provinces autonomy issues. The same conflict led to dismemberment of the country in 1971 with direct interference of Hindustan. Although the 1973 Constitution has clearly settled the issue legally, yet undercurrents in political life of three minority provinces do hint on a potential conflict area which enemies of Pakistan feel convenient to exploit.

The Present Challenges

In the last 75 years, Pakistan as a nation made substantial gains. Pakistan started its journey with almost a zero account as a nation but today we are a nuclear power, being counted in the top 10 military powers of the world, GDP growth ranks in the first 30 countries, our cities are thriving, and literacy rate for both genders has improved. However, despite this there are serious challenges to our nationhood.

§ Economy. The worst among all is the almost dilapidated economy which is breathing on foreign loans and grants. Our foreign reserves are shamefully so low that our friends have to lend us money as a guarantee to arrange for more loans. If the situation is not addressed quickly then for how long can we sustain as a nation on other people’s money? The ever burgeoning unemployment of youth is a volcano that can erupt a social and political turmoil. Often our ruling elite is found complaining about diminished exports, but there is no national realization that despite being called an agriculturist country, we don’t produce enough to sustain ourselves and rely on food imports.

§ Politics. Politically we are a house divided. In such a mess that cries of bloody revolution, which is no indication of a healthy society. We have not been able to mature our politics where it should mean more than opportunism, corruption and election sloganeering. To meet people’s rising expectations, one easy way of our politics has been to acquire loans and subsidize life for people. Politics is not leading the people to a strong nationhood but renting those to foreign lenders in such a way that the future will not belong to us. Pakistan has tried martial laws in the past, but those also didn’t work and again had to revert to democratic system. However, our democracy has not been able to deliver efficient governance. The continuous obstruction to district governments by the political parties is in fact anti-people. Similarly, there is a clear lack of trust between politics and various institutions, and this mutual suspicion and maneuvers seriously dent the nationhood. We must never forget that it is not the riches that strengthen a bond, but predictability and consistency that nurture a lasting trust for the growth of a healthy nation. Ironically, we have neither riches, nor predictability and trust!

§ Power Distribution. Although the 1973 Constitution has significantly resolved the power balance issue between provinces and the center, there is a growing concern among a significant portion of the national leadership that after 18th Amendment the center has become weak, particularly its financial health. Similarly, by grant of education as a provincial subject, the national narrative for future generations will get a relegated attention. It is a bitter irony that provinces in Pakistan have more distinct and powerful ethnic identities, and if popular politics are exploited, will nurture a centrifugal culture than uniting all in a single nationhood. India is continuously feeding all types of dissident elements to damage the federation of Pakistan. Afghanistan, despite its worst sufferings, still is never hesitant to air its irredentist claims or fueling the ethnic movements. There are numerous examples in the recent past which make it evident that foreign threat to Pakistani nationhood has not subsided.

Need for a Consensus

Pakistanis are celebrating the golden jubilee of their independence in an economically precarious, politically fractured and socially decayed society, but we have a future and can build it for proud centenary celebrations in 2047. The good thing is that despite many low points, we have a Constitution, a parliament, nationwide political parties, functioning national institutions, a vibrant media, and a middle class that is keen to change things for the better. All we need is a national dialogue to achieve a national consensus on various long term goals. The parliament can lead this process by making various Pakistan National Dialogue and Consensus Committees for 2047 (PNDCCs-2047). These committees should comprise members from parliament in lead roles, and others in all fields including representatives from establishment, economist, scientific and social sciences academia, media, lawyers, etc. and make actionable policy guidelines for the next 25 years. Pakistan had enough ideological debates, therefore, these policies should aim at tangible economic, education and political goals. In the last 75 years, one factor has been established that the federation of Pakistan has always reverted to democratic practices, and now the need of time is to reinforce it with suitable changes to make it efficiently functional. If there can be separate democratic models by the US, UK, China, Germany, France and many other countries, then Pakistan can also have its distinct model in line with its history, demography and aspirations. These PNDCCs-2047 can take a year-long time to answer these questions given below and formulate tangible plans for achieving Pakistan 25 Years Nation Plans & Goals (PNP&G-25). After PNDCCs have finalized these goals, the same PNDCCs can select National Oversight Committees from its members on a 25 years basis, and make it part of the Constitution for the next 25 years through an amendment. The likely area to focus can be:

o Agricultural self-sufficiency and exports.

o Industrial growth and exports.

o Meeting energy needs of the country (only reliance on water, solar or atomic).

o Population growth and related issues.

o Building communication infrastructure particularly railways for national and international trade.

o Implementing a local government system for efficient governance.

o National education policy to substantially promote scientific enquiry, social growth, national cohesion and market based functional/vocational knowledge.

o Power balancing between center and provinces to ensure a viable relationship meeting needs of national unity and provincial autonomy.

o Intra political party democratic practices to avoid perpetual dynastic political hegemony.

o A well regulated law-bound harmony between institutions and politics keeping in view the past experiences, and thus ensuring institutional autonomy as well as overstepping by them.

o Ensuring merit and checking corruption by resorting to technology and transparency.

o Regulating media for the good of society without impinging upon freedom.

o Pursuing the goal of accumulating $100 billion as foreign reserves which are to be maintained at all times (The spendthrift tendency to deplete foreign reserves in the name of development projects and later subsidizing through foreign loans should be made a national taboo).

A well-constructed Pakistani nationhood for our future generation is awaiting for our timely and selfless response! All is constructed in this world and nothing is an impossibility for a collective national will.