Chief of the Army Staff (COAS) General Qamar Javed Bajwa is in a race against time. If everything goes according to the announcement made by the current military spokesperson, General Bajwa is all set to retire by the end of November this year, after completing his second three-year term as the COAS. This leaves barely five months for the most influential and powerful man in the country right now to oversee and guide to completion what his supporters say is “the process of institutional course-correction” which began with the announcement of a new ‘neutrality’ of the Armed Forces on Pakistan’s political chessboard.

However, this apparently “politically correct” posture — that has long remained the demand of Pakistan’s traditional anti-establishment forces — has triggered a sharp reaction among the Pakistan Army’s many ardent civilian supporters and cheerleaders. They see this institutional “neutrality” as directly or indirectly responsible for the return of the country’s two allegedly most corrupt political dynasties — the Sharifs and the Zardaris — into the corridors of power.

And in the battle of optics and perceptions, the unexpected fall of the Imran Khan government seems to have exacerbated Pakistan’s political, economic and institutional crises.

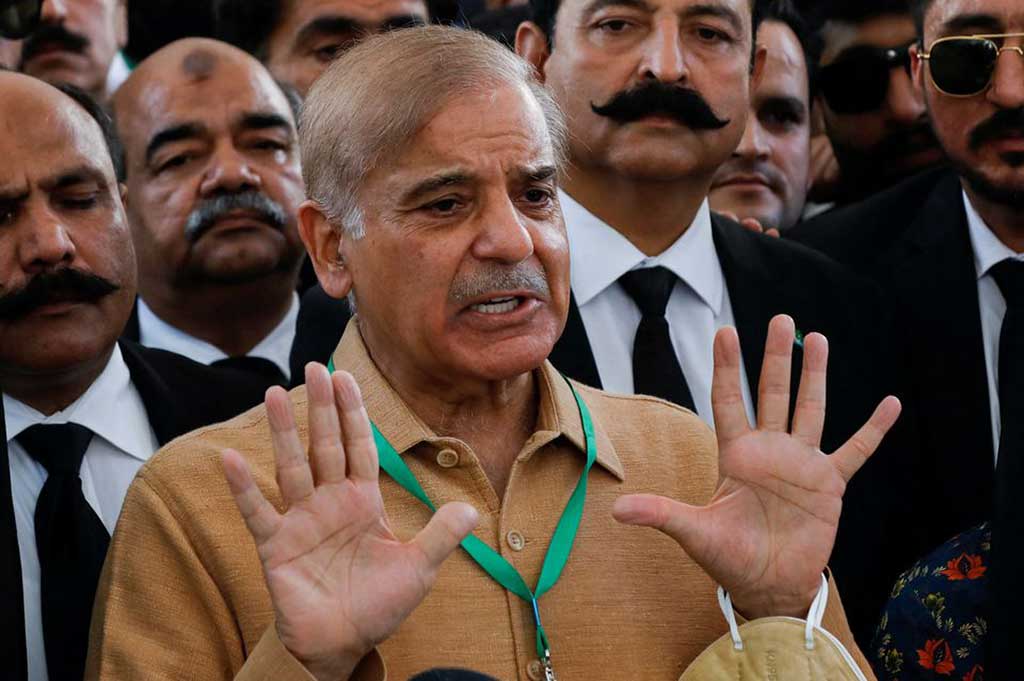

The political polarisation has intensified against the backdrop of the once again soaring popularity of Imran Khan — which had ebbed considerably during his time in office. Now he is seen as holding a far higher moral ground than his political rivals. And as both he and his opponents — the unity government — have dug their respective heels on two opposite ends of the political spectrum, there appears no middle ground for any workable relationship. To discredit the system even more, the incomplete National Assembly is seen passing controversial laws, clearly and solely aimed at benefiting the Houses of the Sharifs and Zardaris and their close aides in numerous corruption cases. The sweeping changes in the National Accountability Bureau (NAB) laws are a prime example of this. Meanwhile, right or wrong, as far as the general public is concerned, all this has been done with the blessings of the powers-that-be.

With more than 120 Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaaf (PTI) lawmakers staying away from the National Assembly after tendering resignations, a small friendly or “pocket” opposition is making the process of law-making murkier. Many Pakistanis, especially the educated and politically-aware segments in the urban areas, have lost faith in the system, and vent their anger by joining Imran Khan’s rallies and public meetings, or taking extreme positions on social media in which they target not just the Shehbaz government, but also the institutions they see as culpable in respect of the current political maelstrom.

Perhaps this expression of public resentment and outrage is the most worrisome sign. Never before in the past, has the Pakistan Army’s top leadership been made the target of a smear campaign on the huge scale being witnessed today. In the past, a tiny segment of “politically correct” westernised liberals, and the fringe sub-nationalist and separatist groups resorted to propaganda campaigns against the Armed Forces, but they found hardly any takers of their point-of-view in mainstream Pakistan. Even when former prime minister, Nawaz Sharif, his daughter Maryam, and some close aides criticised the military leadership, including the Army Chief General Bajwa, by naming them in their rallies, a vast majority of Pakistanis reacted strongly against them and rejected their narrative. But this time around, the situation is different.

Former premier Imran Khan often speaks in metaphors and makes indirect references against those who brought what he calls the “most corrupt” politicians back to power, but he tactfully refrains from making any direct allegations against the Army or its leadership. In fact, both in his on-the-record and off-the-record interviews, he always highlights the vital importance of the Armed Forces for a country like Pakistan.

However, a large number of his fans, and those who oppose the Sharifs and the Zardaris, are not following suit, or paying heed to Khan’s advice. They are continuing with their propaganda against the military leadership. And perhaps for the first time, many retired officers of the armed forces, including senior level officers, have also joined these voices of protests — such a break from the past being unheard of in Pakistan’s history.

This kind of mass public criticism cannot be simply brushed aside as the work of anti-Pakistan forces or an organised campaign by some vested interest or a political party — the PTI. Something unprecedented is happening in Pakistan, where people are questioning the sudden shift of the military’s own narrative on both the regional and domestic fronts. For them, the country’s “centre of gravity” now stands shaken, if not compromised.

Even before the change of guard in Islamabad, Many nationalist Pakistanis were upset at Pakistan’s soft and lacklustre stance, including that of the Army Chief, in relation to India and the assimilation of occupied Kashmir into Indian union territory. Barring some lip-service to this cause for internal consumption, Pakistan’s climbdown on this front has been stark and shocking for many Pakistanis. Statements such as it being time to “bury the past” and “regions must go forward” have not gone down well among the people considering that India’s extremist Hindu government is resorting to the worst kinds of atrocities in occupied Kashmir, and also against Muslims living in India in general.

Now the rise of the Sharifs and Zardaris to power is seen as another institutional climbdown even on the domestic anti-corruption narrative which had been consolidated and nurtured for years. Similarly, on the media front, there has also been an about-turn in the institutional position. Now those media houses which had remained the target for years, are being patronised and cultivated, and those which were seen as being close to the establishment, are being sidelined and shunned.

Whether for good or for bad, these are mega shifts in the Pakistan Army’s position that will have a long-term impact not just on the institution itself, but also on the country. The biggest question for Pakistan watchers remains whether Gen. Bajwa will be able to finish what he started in the fag-end of his military career. The military top brass also needs to do a lot of introspection on why the country’s most trusted and most popular institution until just a few months ago, failed to put across its message effectively, logically and rationally. Why has there been such a huge disconnect between the public and the barracks? And why was the institution not able to correctly read the mood of the moment?

However, it is not just the “institutional course correction,” and its impact on politics and optics which remain a challenge for both, the military and civil leadership. The reality of a severely strained economy is making this task even more difficult and unpopular.

Although on many fronts, Pakistan’s macroeconomic numbers are impressive — for which credit should be given to the Imran Khan government, including the rise of exports, a higher tax collection and the inflow of remittances — exogenous shocks have made imports too expensive, leading to a balance of payments crisis.

The measures taken by the Shehbaz government to revive the International Monetary Fund (IMF) programme, including jacking up petroleum products’ prices and electricity and gas tariffs have already resulted in record inflationary pressure. Going forward, inflation is all set to increase, which will make the current government and its supporters even more unpopular and provide Imran Khan greater ammunition to carry on his tirade against them.

While the Shehbaz government has floated the idea of an economic charter and a consensus on economic policies, the hard fact is that no country can fix its economy without ensuring political stability. And unfortunately for Pakistan, this stability will remain elusive because those who are leading the country are not seen as honest and above-board. This perception is one of the many stumbling blocks that is preventing Pakistan from exploiting its huge potential. Many Pakistanis are justified in asking how those responsible for bringing Pakistan to its knees economically and amassing huge wealth in foreign countries, can be trusted to once again lead the government.

This lack of confidence and overall negative perception is now like a millstone around the neck of the current military and civil leadership. The perceived union between the Army leadership and those accused of corruption is badly hurting the credibility of the institution and its leadership. But, for the corruption-tainted politicians it is a win-win situation. They are not just back in power, but are also now exploiting the system to manage their cases and advance their interests.

The military leadership appears in a catch-22 situation, as on one hand it is facing a backlash from its own popular support-base — so vital for any country’s security — and on the other hand it is being accused of selecting those civilian partners who enjoy little respect among the people and are historically seen as unreliable by the institution itself. A continuing environment of political instability and confrontation remains bad news for any country, and it is in the state’s enlightened self-interest that it resolves such internal contradictions on a war-footing.

The deepening political crisis is not just putting pressure on the Armed Forces, but also on the other state institutions — from the judiciary to the Election Commission of Pakistan. There is a lot of disillusionment and discontentment towards the performance of these institutions, as the powerful, politically connected and corrupt elite now seem to be unstoppable.

Given the public mood and reaction, the way forward cannot be expecting tried and tested politicians to pull the country out of the morass, but rather on disengaging them. And the people know this cannot happen if this so-called unity government is kept in power in Islamabad and Lahore. Perhaps a truly neutral set-up comprising experts and technocrats, with a mandate to steer the country through difficult economic times is the answer to the problem for now

While the Pakistan Army leadership is under severe criticism, allegations of corruption and misrule against Imran Khan seem to make little impact on his fan-base. He is largely seen as the Mr. Clean of Pakistani politics, and the criticism that he attempted to interfere in the working of the army, made a bad choice regarding the chief minister of the Punjab, messed up Pakistan’s foreign relations with friendly countries and remained uncompromising in his relations with the opposition, is also not creating any significant dent in his popularity. In fact, some of the charges leveled against him — of him being hawkish and uncompromising on corruption and saying a firm no to the alleged dictation of foreign powers — are going in his favour. Currently, Imran Khan is the voice of all the country’s popular narratives — from his anti-corruption crusade to saying no to foreign dictation, from the need for pro-poor measures to getting his inspiration from the Riasat (State) of Medina.

But it does not mean that the road ahead for Khan is smooth. He is seen taking on the country’s entrenched political establishment, the media establishment and the military establishment all at the same time. His only card right now remains that of a popular support base, even though his core team appears weak and disorganised. And yet, vested interests are finding him hard to manage with every passing day.

For General Bajwa, defusing these ever-escalating political tensions remains a prime responsibility — and a major national security challenge.

Given the public mood and reaction, the way forward cannot be expecting tried and tested politicians to pull the country out of the morass, but rather on disengaging them. And the people know this cannot happen if this so-called unity government is kept in power in Islamabad and Lahore. Perhaps a truly neutral set-up comprising experts and technocrats, with a mandate to steer the country through difficult economic times is the answer to the problem for now. State institutions must also ensure that an across-the-board accountability agenda is rebooted before the country holds fresh elections. The work can only start from the dissolution of these compromised and controversial assemblies. But who will bell the cat?

Gen. Bajwa can still leave a legacy by facilitating the steps needed to take Pakistan towards political stability and progress. Can he do it? Will he do it? Or will the institution itself do what it is required and expected to do? The entire nation waits with bated breath; whatever steps the military leadership takes or does not take from now, will have a direct bearing on the future of Pakistan — good or bad. The ball is in their court.