We Pakistanis mostly see our country’s greatest friend and strategic partner, China, through the lens of propagandist Western media, thinktanks, and writers. It is somewhat ironic that despite our close ties, in Pakistan, very little original work on China’s history and political system is produced or analysis done on its rapid rise on the world stage as the second largest economic power that is all set to first catch up with and then outpace the United States.

Ali Mahmood, a prominent Pakistani businessman, politician of yesteryears, and author, attempts to understand the Chinese marvel through his book, Enter the Dragon: The Story of the China Miracle, published in January 2021.

This is Ali Mahmood’s third book, following Saints and Sinners (2013), and Muslims (2017). And like his previous works, Enter the Dragon too, is based on in-depth research and written in his typical, easy-to-read, breezy style, like a dramatic novel.

As the book gives a fast-paced account of Chinese history, the reader meets revolutionary icons — from Mao Zedong to Deng Xiaoping — and the new breed of leaders of post-revolutionary days — from Hu Jintao to Xi Jinping. One also gets a glimpse of Chinese entrepreneurs and businesspeople, whose numbers are rapidly increasing in the world’s billionaire club.

Painting sketches of real-life people — showing their strengths and weaknesses, achievements and failures, wisdom and follies, is one of the skills Ali Mahmood exercises when writing, which he has also demonstrated in Enter the Dragon, just like his previous works.

The book, divided into 18 chapters, narrates Chinese history through gripping anecdotes and characterisation of larger than life personalities, as it offers both the bird’s eye view, and at times, the worm’s view of landmark events.

From the “Century of Humiliation to a miracle economy,” how did China achieve its mega-growth in less than 100 years? What role did its remarkable leaders play in this transformation? Why did their experiments to consolidate the revolution and make it more pro-people, at times, fall short of the target, and that too, at a great human cost? What lessons were learnt and how was sustained, rapid economic growth achieved?

Enter the Dragon attempts to answer these complex questions in broad strokes, as it also highlights China’s continued struggle against corruption and crime, introduces Chinese princelings, billionaires, and the party, highlights mega projects and the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), and discusses its foreign relations, especially the ongoing ‘war’ with the United States.

According to Ali Mahmood, “by combining the romantic vision of the idealistic guerrilla fighter, Mao, with the pragmatism of the determined reformer, Deng, the People’s Republic of China was created, strengthened, and steered through problems and difficulties.”

The book starts with a brief history of the creation of unified China in 221 BC, when Emperor Qin Shi Huangdi put an end to the period of “Warring States by conquering the six kingdoms … with his sheer force and ruthlessness.” His tactics may appear cruel, but his “efficient dictatorship created exceptional infrastructure and development and capped it with his most famous construction project, the Great Wall of China.”

Fast forwarding the landmark events of ancient China, the author takes the reader straight to the 19th Century, remembered more as the “Century of Humiliation,” when the Europeans had established their hegemony, and an insulting signboard in a Shanghai park read, “No dogs or Chinese allowed.”

Even after the First World War, Imperial Japan occupied China’s Shandong province, sparking protests among Chinese students and intellectuals, giving birth to modern Chinese nationalism, which carried the seeds of the Communist Revolution.

But the road to revolution is never straight, nor is it black-and-white. It is a complex, multi-pronged struggle fought on many fronts. On one hand, if the battle lines are drawn against the ruling classes, their allies as well as foreign powers and their collaborators, then on the other, there is always a bitter and sometimes even bloody inner-party struggle among comrades-in-arms on strategy and tactics. The Chinese revolutionary struggle also passed through this murky phase and uncertain times in which Mao Zedong emerged as the supreme leader of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

This phase is incisively summed up by the writer, detailing how the legendary “Long March,” started as a “desperate retreat” but proved “a prelude to victory,” decisively establishing Mao’s leadership.

“The Long March” is a story of courage, sacrifice, hope, endurance, and determination through indescribable hardship. Of the 85,000 soldiers who started the march, 8,000 survivors arrived at their destination a year later.”

In a fast paced, gripping way, the author narrates in condensed form the bloody post-Long March struggle that brought Mao to power, defeating both the Japanese occupation forces and the Chinese nationalists led by Chiang Kai-shek. Then, Ali Mahmood immediately moves to the triumphs and tribulations of Mao during his days of absolute power. “Worshipped as a demigod for having achieved the impossible, he (Mao) inspired the belief that the future held no limits.”

Yet, difficulties for the newly created People’s Republic of China were immense. “The people were poor, the industry in shambles and the nation bankrupt… The US was committed to Chiang Kai-Shek… Russia meant Stalin, and Stalin was a difficult man to deal with,” the book says.

Against this backdrop, Mao and his struggle-hardened team set to work to rebuild and change China. But soon Mao had to make the difficult decision of joining the Korean War, which meant taking on the United States, the new superpower of that time. The decision was taken despite the fact that the Soviet Union had backtracked from its promise of providing air-cover to communists. Chinese involvement in the Korean War brought the American troops to a standstill, “but the cost of war both during and after was too high.”

“Close to half a million Chinese soldiers were killed… including the young son of Mao.”

China had to face crippling US sanctions which hampered its growth for the next 20 years, “but Mao and China’s reputation had been established the world over,” says the book.

On the home front, Mao launched a drive against landlords, redistributing their lands among farmers, and taking on the counter-revolutionaries. These campaigns resulted in over 1.7 million deaths.

Being a “people’s man,” Mao hated elitism. “To bring them (party members, officials) to heel,” Mao launched “anti-corruption, anti-waste, anti-bureaucracy” campaigns.

The author gives details of the sweeping measures Mao undertook to reform, change, develop, and modernise China on every front; fighting the class enemies, holding his party comrades accountable for indulging in corruption, and creating a new culture which “demonised the enemies of the party and praised the new socialist regime.”

In the fascinating account of Mao’s era, the Chinese leader emerges as a romantic revolutionary, committed to his ideals and ideology, and love for his people. In a short span, “Mao had unified China, created an impressive rate of growth, restructured the education system, improved living standards, and fought the United States … to a standstill in Korea.”

“But success on so many fronts in the face of so many problems, intoxicated Mao who had never seen defeat over three decades and had yet to learn that pride comes before a fall,” the author wrote, explaining Mao’s dilemma.

“The Great Leap Forward was a campaign to accelerate growth… and overtake Great Britain in 15 years,” but it proved “Mao’s greatest miscalculation and his most tragic mistake leading to death by starvation of up to 30 million Chinese.” Recognising the disaster, Mao stepped aside in 1962, only to bounce back four years later through the Cultural Revolution, which started in 1966 and continued almost till his death in 1976. Unlike most western writers, who demonise Mao for the Cultural Revolution, Ali Mahmood gives a different take, highlighting why it was launched and discussing both its positives and the unintended negative consequences.

“Mao believed in equality and was disturbed by the party bureaucratic elite who ruled rather than served the people. The Cultural Revolution attacked this corrupt tendency across China to abuse power for personal advantage: it gave people a sense that they were equal, not inferior, to the privileged,” the author writes.

Moreover, the author also states that “elitism was replaced by equal opportunity, practical education replaced mere theory and rural education grew. The obstacles to mass education were erased as costs and duration were reduced… Educational reforms were ideological (red), practical (vocational) and aimed at the masses (rural).”

Therefore, the writer is shedding light on Deng’s economic miracle as being made possible only because of the foundations laid down by Mao.

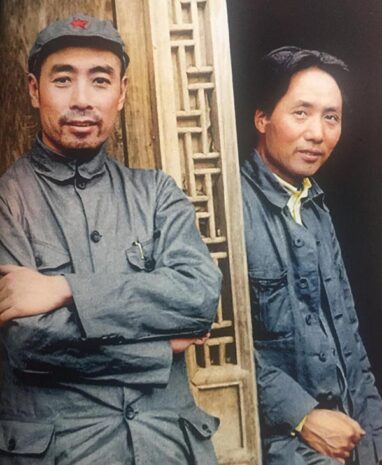

Deng was Mao’s companion during the struggle and they had been roommates. Deng was close to Mao, yet he also suffered at his hands. He was purged in 1966, yet Mao did not allow any extreme steps against Deng and finally called him back to Beijing in February 1973.

From there on, Deng “understood the importance of staying on the right side of Mao while pushing forward with his policies and the handling of administration.” Deng had three battles to fight. “First the difficult job of running a government in crisis, second the infighting in the court of an ailing Mao close to death, and, last but not the least, his handling of a moody and mercurial leader.” And Deng emerged victorious on all three fronts, becoming the new strongman of China after Mao.

Ali Mahmood (author) sums up Deng’s strategy and his key to success in his typical one-liner. “Deng had shown his resolve – economic reforms yes, democracy no.”

The writer says, “He (Deng) replaced ideology with the economics of capitalism with socialist characteristics. He had done more for his nation and his people than any other world leader of the 20th century.”

Deng’s successors, from Jian Zemin to Hu Jintao and then Xi Jinping, kept the economic reform process going, attracting foreign investment and transforming China into an economic power house, expanding its economic growth at a breath-taking pace of an average 9 percent since 1978, maintained for over 40 years.

Furthermore, the author explains that China’s rise has been peaceful. Deng had advised, “Lie low and bide your time.” But by the time Xi Jinping assumed power, China had practically eradicated extreme poverty and with its new trade surpluses and growing wealth, it started to look like a competitor to the United States, which ironically helped its rise.

“Xi also wanted the world to see that China had become strong. China already had a strong economy and a stable government. Now Xi focused on creating a strong army capable of combat; this meant less troops but more technology,” the author comments.

Highlighting the contrast between the Chinese and US approach, Ali Mahmood writes that China’s military budgets remained far below America’s, but China needed its army only for defence.

“China wanted to dominate the world through trade and its economy; America wanted to control the world through its army rather than through negotiations and common interest.”

In this context, Xi’s One Belt, One Road initiative emerges as the greatest infrastructure programme in human history, benefiting not just China, but many Asian, African, and European countries.

“Whereas America, in the twentieth century, had provided millions of dollars, China, in the twenty-first century, provided billions. And China’s support was unconditional, unlike the USA, whose interference had led to the saying in the developing world, ‘Be careful, or America will punish you with democracy.’”

The book rightly pointed out that America’s posture as the champion of democracy remains “hypocritical and opportunistic,” offering an objective comparison between policies of China and the United States.

One of the nuggets in the book says that “the US economy relied on debt-based over-consumption; China’s economy on debt-based over-investment.”

The book gives an insight into China’s growing stakes in Africa and the Middle East and into how Chinese money and technology are helping many developing nations to modernise and change the lives of their citizens for the better.

The chapters on China’s long struggle against corruption and crime, the influence and clout of descendants of the Long March heroes, described as princelings, and on Chinese billionaires help the reader to understand China, its society, its work ethics and world view better.

The chapter on the CCP’s — which grooms and develops leaders on merit — might, working an all-encompassing control over the country, is not just an interesting read but also shows third world countries that western democracy is not the only path to development and modernisation.

According to Ali Mahmood, “many poor countries tried democracy, but it did not make them rich because it was not democracy but military strength that created the wealth of the West,” through the loot and plunder of colonies.

“Later (it) allowed the US to impose a dollar hegemony… in which the countries of the world produced goods to sell to America, and America produced dollars to buy the goods.”

The book celebrates the success story of China by highlighting some of its grand mega projects, which are the biggest in the world, including the South-North Water Transfer Project, the Three Gorges Dam, and the High-Speed Rail Network.

From the perspective of Pakistani readers, Enter the Dragon is indeed a rare and valuable addition to the small number of such works written by Pakistani scholars and writers. For anyone interested in understanding China and its miraculous existence, Ali Mahmood’s work offers a one-book solution.