Many Karachiites believe that deteriorating civic amenities, transport problems and even ethnic conflicts in Karachi are all consequences of administrative mismanagement and lack of political will to solve problems of this megacity. However, in this paradigm, the demographic dimension is rarely mentioned. This article analyses the multidimensional problems of Karachi with a demographic perspective and explain its implications for deteriorating civic amenities and infrastructure, which leads to an overall disenchantment among its residents.

If one analyses the problems that Karachi has faced for more than four decades, one key factor remains its unchecked population growth. In the mid-19th century, Karachi was a small town. When the British General Charles Napier conquered Sindh and landed here in 1843, Karachi’s population was 14,000. He later served as the governor of Sindh and termed Karachi, the “Pearl of Asia.”

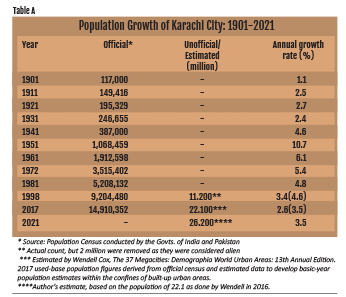

According to the first census conducted in 1881 by the British, Karachi’s population was 74,000, which increased to 105,000 in 1891. The growth of Karachi’s population since 1901 is shown in Table A. The figures derived from the past two population censuses, particularly for 2017, are highly disputed. They are far below estimates by an international organisation.

Migration to Karachi

One of the main reasons for the rapid growth of Karachi’s population during the past 70 years is constant migration to the city from other provinces. Since the beginning of the 20th century, Karachi has opened its arms to all kinds of people. The 1901 census counted 117,000 inhabitants in Karachi, which later grew at an average rate of 3 percent per annum and recorded a population of 387,000 in 1941. Thus, during the pre-independence period, Karachi’s demographic growth was manageable. However, in 1947, with the Muslim refugees coming in from India, within a year, Karachi’s population swelled to over a million. Perhaps, Karachi is the only large city in the world to record such phenomenal growth within a year.

Even after the influx of refugees in 1947, Karachi’s population growth remained high and continued unchecked for several decades. It started in the early 1960s, when there was an influx of migrants, who originated mainly within Pakistan — from Punjab and NWFP. Thus, the representation of the native Sindhi and Baloch population became smaller. For example, the 1961 census reported the mother tongue of 8.6 percent of the population as Sindhi and 5.3 percent Balochi, which was reduced to 4.8 percent and 3.7 percent, respectively in 1998, while the percentage of those speaking Pashto increased from 5.2 percent to 11.5 percent and Punjabi-Saraiki speakers increased from 12.8 percent to 16.4 percent, during the same period. The 2017 census data on mother tongue has not been released yet, but indications are that the percentage of those speaking Pashto and Saraiki have increased further due to migration from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) and Southern Punjab during the past two decades.

The results of the first four censuses since Independence show that between 1951 and 1981, Karachi’s population grew over five times, from 1.0 million to over 5.0 million. The situation has become alarming since the 1980s, as the rate of natural increase (births-deaths) remained at about 3 percent per annum, resulting in the addition of an average of about 250,000 babies to the population every year. To aggravate the situation, about 250,000 migrants from other provinces moved to Karachi annually. A majority of them, being below the age of 40, were new entrants in the job market. During 1951-81, Karachi’s population recorded about a five-fold increase as compared to 2.5-fold increase in Pakistan’s population.

Among many injustices done to Karachi, one of them is that the federal government has been unwilling to count the exact number of people who live in Karachi. Thus, the 1998 census, counted about 11.2 million inhabitants, but conveniently removed two million people from the official report, as they were considered citizens from other countries, such as Afghanistan, Bangladesh and Burma. Even with the undercount (or removal) of about two million people from the official records, analysis of the 1998 census data indicated that the population size of Karachi Division then was 9.8 million while the combined population of Lahore and Sheikhupura was 9.6 million. During the 10 years preceding the 1998 census, Karachi received almost twice the total number of internal migrants than Lahore-Sheikhupura combined (22 percent and 12 percent, respectively).

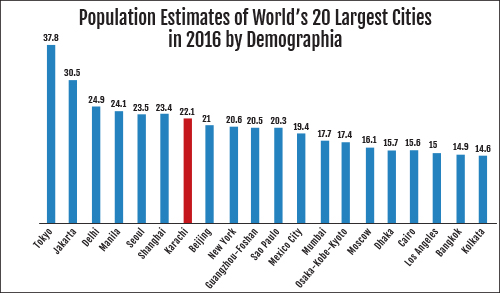

Information on migration was not collected in the 2017 census. However, Demographia — a prestigious international organization — in 2016 estimated Karachi’s population at 22.1 million, while the 2017 census counted 14.9 million people a year later. Thus, either over 7 million inhabitants of Karachi were not counted in the census or they were counted but were included in the provinces from where they had migrated. Perhaps the purpose of under-reporting Karachi’s population in the two previous censuses was that the percentage of Sindh and Karachi’s share in national population remains the same as reported in the 1981 census. This way Sindh does not get its due share in the country’s resources through the National Finance Commission (NFC) awards nor does Karachi get proper representation in Parliament. Due to the alleged undercounting of Karachi’s population in 2017, the census results have remained in dispute till today. Consequently, along with the Chief Justice of Pakistan, the Sindh Assembly, academics and scholars as well as the media have refused to accept the figures released by the government. Indeed, all the political parties of Karachi are demanding a fresh census in the city.

Growing Stature of Karachi

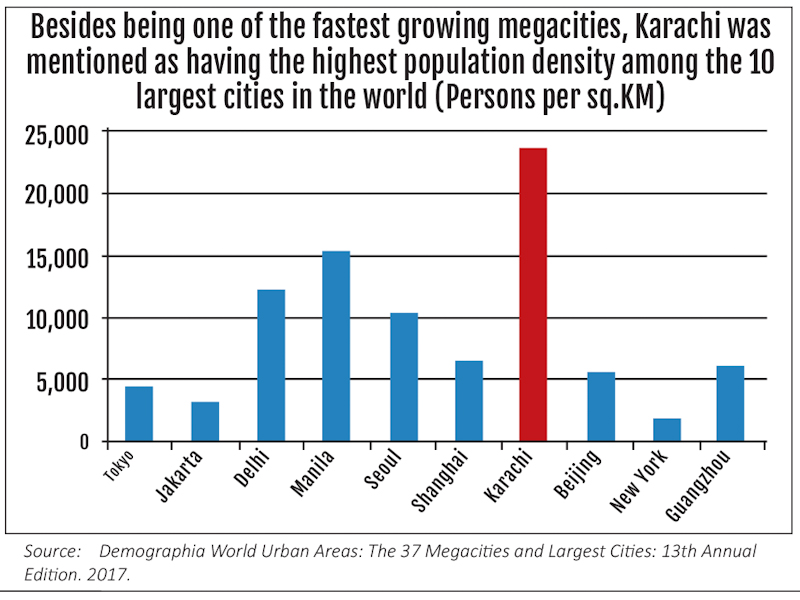

In 1970, with a population of 3.1 million, Karachi was not even ranked by the United Nations amongst the 30 largest cities of the world. In 1990 with a population of about 7.1 million, it was ranked as the 28th, having about half as many people as New York and about four million more than Mumbai, and about three million more than Calcutta and Cairo. In 2016 Karachi was ranked by Demographia as the 8th most populated city in the world, with over 24,000 people crammed in per square kilometre.

Consequences of this unchecked growth of Karachi’s population are many. A high growth rate means an age structure where the proportion of the dependent population is increasing, so much so that over half of the population is under 20 years of age. These young migrants, who move every year to the city mostly from rural areas, to seek employment, number in the hundreds of thousands. The city at the receiving end gets an additional army of unemployed and uncontrollable youth.

The vulnerability of youth (especially in the age group 15-29) is well known. Any radical ideology can be sold to them. Thus, they can become one of the most important forces behind street power. They are also vulnerable to crimes, drugs and economic exploitation against the backdrop of the loosening control of the family.

The majority of migrants, who are attracted towards Karachi for its so-called glamour and wealth, unfortunately find neither and end up in katchi abadis, where an estimated 40 percent of Karachi’s population lives. The ethnic tension in the city which emerged in the 1980s and continues till today, is the product of the fast growth of the migrant population, deprived of basic civic amenities, which they expected to enjoy on the one hand, and the rising tide of expectations among the native population, on the other. Many youngsters from both sides — looking for adventure — often fall into the trap of unscrupulous political, religious and even criminal groups and are dragged towards violence and crime.

Ethnic Diversity

Karachi is one of the most diversified cities in the country and Asia. Less than 10 percent of Karachi’s population consists of native Sindhi and Balochis, about half are migrants from India and their descendants, about 5 percent are immigrants from Afghanistan, Bangladesh and Burma and over one third are internal migrants from other provinces. Even now, the process of migration from all over Pakistan is continuing, which further aggravates the situation.

The city faces so many social and civic problems that proposing possible solutions requires much more than is envisaged by our planners. Unfortunately, when it comes to solving Karachi’s problems, many who matter, as well as pessimists, consider Karachi as “a problem,” because they see no hope. However, optimists still think in terms of “solving Karachi’s problems” in the best interest of the city and the country. One could suggest a few solutions.

On the demographic front, the problem should be dealt with at two levels. A natural growth rate of 2 percent for a city like Karachi is too much for any population to sustain. Many Asian cities from developing countries such as Shanghai, Beijing, Bangkok, Jakarta, Dhaka, Calcutta, Delhi, Mumbai, Tehran and Istanbul have an annual natural growth rate of population that is half of Karachi’s. There is no reason why Karachi’s rate of natural increase could not be reduced to 1 percent — especially when the city’s population is far more educated than the rest of the country and most of it has access to television and mobile phones. However, to do so, more concerted efforts are required to reach couples, particularly those living in low-income areas, through innovative community-based programmes. However, reducing the birth rate in Karachi alone would not solve the problem. Similar efforts are needed in the countryside, where birth rates are too high and since the agrarian economy cannot absorb the excess labour force, young people are forced to migrate to Karachi.

Secondly, efforts are needed to make Karachi less attractive for migrants. One way to do so would be to start dialogues with the provincial governments where migrants are originating. This dialogue would help in devising schemes, to provide residents employment opportunities close to their homes so that they remain within the province. However, if that fails, then at least the sending provinces should share in the upkeep of their residents, who are constantly moving to Karachi. This could be done through proper legislation such as putting employment restrictions on recent migrants to Karachi. Although they cannot be denied secure jobs in the informal sector, local and provincial governments, private organisations and other corporations could be encouraged not to employ them. The new migrants should not be allowed to drive public and private vehicles as professional drivers, unless they have genuine local licenses after receiving proper training, which become valid only after two years of their residence in the city. For the purpose, many jobs in the public sector, including issuing the driver’s license have to be transferred to the metropolitan government, to be manned by locally hired and properly trained staff. Finally, no new katchi abadis should be allowed in the city, as they encourage many new migrants to come here along with their families. These restrictions on new arrivals could produce results eventually. However, there should not be any restrictions on the migration of people from within Sindh province to Karachi, since the city belongs to them as much as to Karachiites.

The solutions to Karachi’s problems can only be implemented if the political will is there, along with the requisite financial and human resources. Concerted efforts as well as financial support are needed. The government must come forward to own the city and its problems. Let the government in power play its role by taking Karachi’s problems more seriously, and tackle them by realigning the political and financial structures to which Karachi’s populace reacts more constructively, through genuine participation.

This city can still be saved from the violence and destruction that is brewing in its overpopulated streets. Otherwise, in the coming rounds of street violence, nobody is likely to be spared.

The writer is a Distinguished Senior Fellow at the School of Public Policy, George Mason University, United States.