On Wednesday, October 21, The News headlines screamed: “Ridiculed, mishandled, demoralised, shocked. Unprecedented protest by Sindh Police, ask for leave.”

According to news reports, the Sindh IG Police was allegedly picked up late night from his house and taken to an undisclosed location. PPP Senator Sherry Rehman remarked, “Making the IG Police hostage to sign on orders of one’s choice is intolerable.”

The Sindh police force threatened to shut shop. The Chief of Army Staff (COAS) intervened to restore peace. The Prime Minister remained silent.

This new development in the polarisation between the government and the opposition aggravates further the issues that have plagued Pakistan’s politics since the country’s inception, in different forms.

The period from 1947 to 1958 was supposedly a democracy. But weak institutions and strong men resulted in a system that was not democracy. When Ayub Khan took over in 1958, he was welcomed. People were fed up with the conspiracies and manoeuvres that culminated in the murder of the Speaker of the National Assembly. People had had enough of democracy; they now wanted a benevolent dictator. At first, it seemed to work in West Pakistan. The situation improved, economic growth increased, the administration functioned better, law and order gave people more security. Stability replaced anarchy, and corruption was brought under control. But by the mid-1960s, people started to wonder — had they made a mistake?

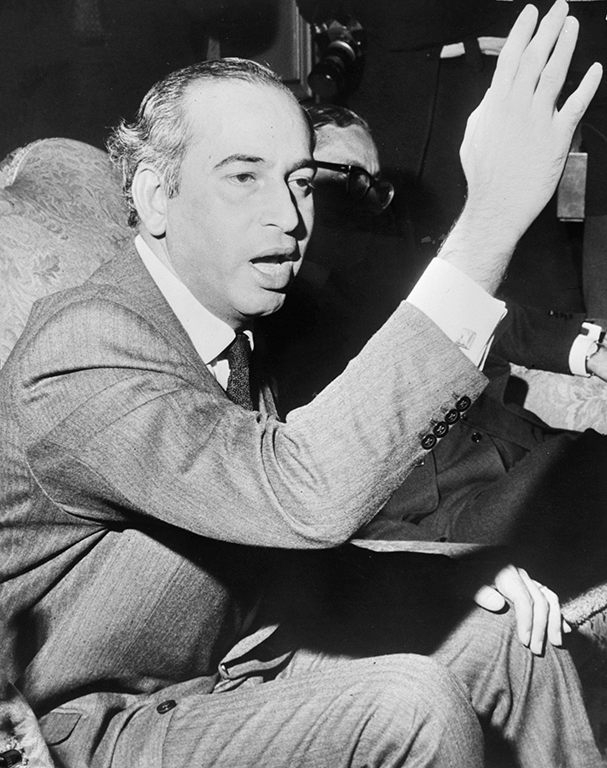

In East Pakistan, resentment grew against the discriminatory treatment of their province. The East Pakistanis felt they had been reduced to second-class citizens, a colony of Islamabad. An uprising had started in Balochistan, and the smaller provinces were not happy with the One-Unit. Industrial labour was bitter that industrial expansion had been at their expense — their salaries stagnated while profits grew. Democrats found an opportunity to oppose Ayub in the 1965 elections, as they rallied behind Fatima Jinnah. People compared the harsh but fair standards of the Nawab of Kalabagh, the then Governor of West Pakistan, who would not even let his own son sit in the official car of the governor, with those of President Ayub, whose son Gohar had become an industrial tycoon in only a few years. The 1965 war with India was a major setback: some blamed Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, but most blamed Ayub. By the time Ayub was removed from power, people had had enough of army rule and benevolent dictators. They wanted democracy.

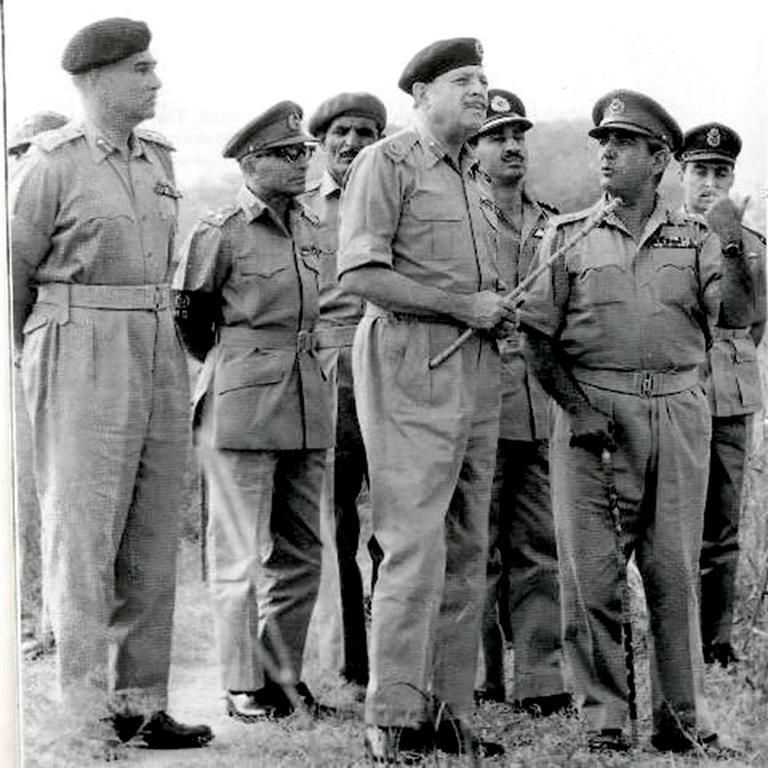

The new president, General Yahya Khan was determined to give the people what they wanted, provided it ensured him the presidency. He fulfilled some important demands before the election: The One-Unit was disbanded, a fair balance between the voting power of the provinces was put into place, and Pakistan was given a free and fair election based on adult franchise. Everyone should have been satisfied. They were — but only until the results were announced: East Pakistan had won a majority in the National Assembly. The only options before Yahya were either to hand over power to Mujibur Rahman, or to resist the result of the elections. Manipulated by Bhutto, Yahya decided to resist. Pakistan was destroyed in the process and Bangladesh was born. Yahya was blamed, army rule was rejected after a lost war in which 90,000 people were taken prisoners of war. Bhutto was installed as Chief Martial Law Administrator.

He called his government a democracy, but soon enough many started calling his rule a mixture of fascism and distorted socialism, based on outdated policies that had already been discarded in China. Economy, law and order, administration and education were destroyed. If democracy meant a Bhutto style of government, people decided they could do without it. When Zia arrested Bhutto and took over, many were ready to accept military rule once again, even if it was led by the unpopular Zia.

To consolidate his position, Zia hanged Bhutto, offered Pakistan to the Americans to fight the Russians in Afghanistan, and enforced his own version of Islam. The result was a culture of drugs and arms, terrorism, refugees, and sectarian war that destabilised Pakistan and made life unliveable. When the general died in a plane crash in 1988, few tears were shed, and the youth who had never experienced Bhutto’s rule, wanted Bhutto’s daughter to take them back to the imagined golden period of Bhutto.

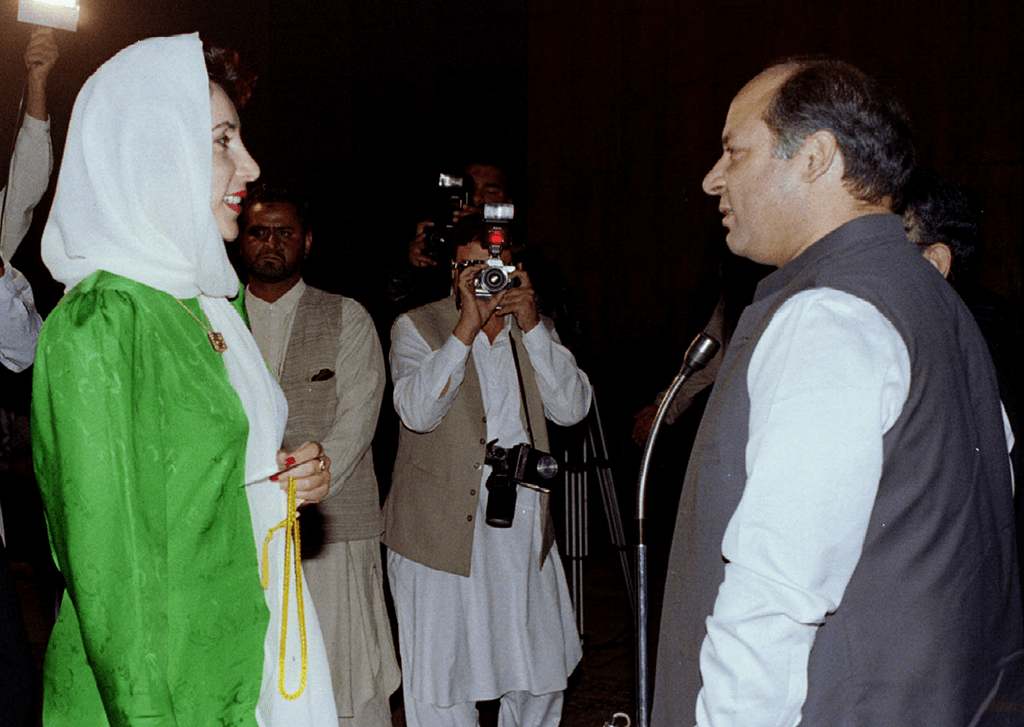

In the decade of democracy that defined the 1990s, the government changed hands four times as two governments of Nawaz Sharif alternated with two of Benazir Bhutto’s. Democracy was in a shambles; corruption, insecurity and maladministration grew to their worst levels. The decade of democracy was a total disaster. When Musharraf finally took over, people heaved a sigh of relief.

Businessmen, bureaucrats, technocrats, and the urban middle classes preferred army rule, provided it was not a Zia-ul-Haq type of government. However, major political parties, lawyers, and the southern provinces of Sindh and Balochistan rooted for democracy. The army was restrained by the constitution. So compliant judges were needed in the Supreme Court to legitimise the army’s takeover with their Doctrine of Necessity and other clever arguments. Till Zia’s tenure, judges could be controlled, but General Musharraf, towards the end of his rule, was to discover that times had changed and judges were no longer prepared to accept a docile and subordinate role.

Ayub had justified his tenure by ensuring economic growth. Bhutto claimed liberation of the masses from quasi-slavery. Zia pointed to the higher growth rate in his tenure, which his opponents argued was misleading since it represented the price for selling Pakistan to the US in their war against Russia. Zia also used Islam to legitimise his rule.

Benazir and Nawaz made tall promises and claimed to represent the masses. But the disastrous decade resulted in a collapsing economy, a terrible rise in corruption, breakdown of law and order, and insecurity of life and property. The frequent elections, as governments were dissolved prematurely, required more and more money. Politics ceased to be a public service and became a deadly business — mafia style — with corruption, cruelty, and killing to secure personal interests.

There was no administration to speak of, as patwaris, police, tax officers and bureaucrats, totally stopped providing services to the public, and became a mafia, extorting money for protection. Without access to power it was impossible to survive in Pakistan. Law had become irrelevant, it was all about access, rishwat and sifarish.

Initially, Martial Law justified its intervention as the only way to stop corruption and ensure good governance. But Zia’s government had proved that military governments were no better. After Musharraf’s takeover, his former CGS, Lt. Gen (r) Muhammad Aziz Khan issued a press statement saying that the entire anti-corruption process had been sacrificed at the altar of expediency as pressure from the presidency ensured that cases did not proceed against the big names. He cited his Chief, Musharraf’s support to the Chaudhrys, Malik Riaz, and many others.

Since even military rulers had to continue with the process of elections, corruption had to be condoned, even supported, to ensure victory for the preferred candidates. The people of Pakistan had lost confidence in both democratic and military rule. After experiencing military rule under Yahya and Zia, military rule had lost its credibility in the eyes of the masses; similarly after the four governments of Nawaz and Benazir, democracy too had lost credibility. Musharraf’s takeover was greeted with a sigh of relief; at least life and property would find some level of protection. Perhaps the rapacious corruption would be checked.

To prolong his rule, Musharraf entered into a secret deal brokered by the US, to bring Benazir back to become prime minister, with himself as president. To facilitate this deal, he enacted the National Reconciliation Order (NRO) condoning all previous corruption. But the best laid plans are often overturned by unexpected events. Benazir was assassinated and Zardari, elected on a wave of sympathy, replaced Musharraf as president. The latter’s handling of the Chief Justice of Pakistan, Iftikhar Chaudhry, proved disastrous. He was forced to doff his uniform, allow elections with the PPP and the PMLN as contenders, and finally to resign as president.

The PPP government that followed is recognised as the most corrupt in Pakistan’s history. Key institutions were subverted. General Kayani, the army chief, was given a three-year extension by Zardari, for which the former remained eternally grateful. The army watched Zardari complete his term.

In the 2013 elections, Nawaz received a massive mandate. But his third term as prime minister was again cut short after the Panama Papers scandal, which led to his disqualification for life by the Supreme Court. He selected Shahid Khaqan Abbasi to replace him, but continued to remain the moving force behind the party.

The 2018 elections brought Imran Khan into power. Khan attacked the corruption of Nawaz and Zardari; he promised to usher in a Naya Pakistan. But within two years, it became clear that the new government was failing to deliver due to its indecisive economic policies, followed by the COVID-19 pandemic. The opposition parties united and began a movement against Imran, whom they called the ‘selected Prime Minister.’ Nawaz, now in exile, attacked the army high command for interfering in politics.

Political observers talk of settlement of the present conflict between the opposition and Imran Khan plus the military establishment in terms of victory and defeat.

They see the Sharif family spending the coming decade in jail or exile. Nawaz is being condemned not just for corruption, but he is also being seen as a traitor to Pakistan. Nawaz says he has been elected three times as Prime Minister, and exploded six test bombs in response to the five Indian blasts. But how relevant are those bombs and blasts in the present context?

In the 1960s, Pakistan was a success story. Today it is not. The deterioration of Pakistan is a result of wars and internal conflict, corruption, bad governance, weak leadership, and the game of musical chairs between civilian and military rulers. These factors have held back education and family planning; have deterred both foreign investors and domestic businessmen from making long-term plans; have led to the flight of both capital and skilled professionals; have resulted in extremely low savings and revenue collection and have made the Pakistan of today a highly indebted state, unable to meet its expenditures for debt servicing and defence, let alone for running the federal government. The rupee has lost value dramatically, both internationally against the dollar and domestically in terms of spending power. In 1970, a dollar cost Rs 5; by 2020 it cost Rs 160, an increase by 30 times. In 1970, the salary of a servant was Rs 60, which grew to Rs 18,000 by 2020, an increase of 300 times. The country is broke.

The most vivid illustration of what is wrong with Pakistan is the Reko Diq project. Reko Diq has 41 million ounces of gold and 50 million tons of copper awaiting extraction, but litigation and accusations of corruption have stalemated the project and the World Bank International Tribunal has imposed a penalty of $ 6 billion, an amount equal to our recent IMF loan.

But negatives aside, Pakistan has also had its share of achievements. It boasts two Nobel laureates, Dr Abdus Salam and Malala Yousafzai; the world’s best squash player, Jahangir Khan; the world’s best bridge player, Zia Mahmood; and the two-time Oscar winner, Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy. Also, it is home to Arfa Randhawa, who at the age of 9 became the world’s youngest Microsoft professional. Additionally, Pakistan is recognised as a nuclear power with the sixth largest army in the world.

The critical question now is, what does Pakistan’s political future look like? How can we build a strong, just and prosperous nation? Is democracy the answer, or is it military rule – or is it neither? China and other successful Asian countries are showing us a new and different way to run our country. Will we rise to the occasion or will we continue to tread the same beaten track?