The confluence of adverse macroeconomic conditions, non-recourse to the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) for fiscal borrowing and uncertain monetary policy outlook have made debt management exceptionally challenging for the Ministry of Finance, which is being forced to accept bids in the government securities auctions at rates significantly higher than the secondary market yields. Speaking metaphorically, the DG Debt is being asked to swim upstream against strong currents while wearing a straightjacket, rendering his position the most unenviable job in the government.

The monetary aggregates encapsulate the interplay of macroeconomic variables, including the developments on fiscal and external accounts. The two fundamental monetary aggregates are Broad Money (M2) and Reserves Money (M0). The latter comprises Net Domestic Assets (NDA) and Net Foreign Assets (NFA) of the SBP, while the former is the sum of NDA and NFA of the entire banking system (the central bank and scheduled banks). The ratio M2/M0 is the money multiplier, which has averaged around 2.8 times over the past three years. A PKR 280 billion increase in M2 requires a PKR 100 billion increase in M0.

With the deteriorating external account, the domestic liquidity conditions are tightening at a time when the government’s borrowing needs are massive due to elevated fiscal deficit and re-financing of maturing debts. The two biggest drains on the banking system liquidity are contraction in NFA and expansion in Currency in Circulation (CiC). While the SBP has been constantly injecting liquidity through Open Market Operation (OMO) for many years, the outstanding amounts have risen significantly in recent months and reached new highs. The net outstanding OMO injection amount of PKR 2.8 trillion at end February 2022 was equivalent to almost 15% of the total banking deposits.

Pakistan has a perennially weak external account and hence the tightening of domestic liquidity conditions are a recurrent phenomenon. Moreover, high CiC growth has been an aggravated problem since 2015. What is different this time around is the restriction on direct government borrowing from the SBP, in place since end-June, 2019 as an IMF programme condition and subsequently codified into law under the SBP Amendment Act passed in January 2022.

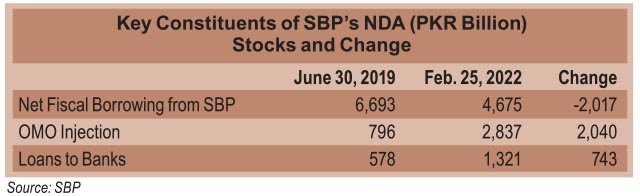

Between July 01, 2019 and February 25, 2022, the outstanding stock of net fiscal borrowing from the SBP (gross borrowing less deposits) decreased by PKR 2.0 trillion. Prima facie, it looks very impressive that a perpetual borrower paid back some of the debts that it owed to the central bank. However, the devil is in the details.

During the same period — from July 01, 2019 to February 25, 2022 — the outstanding amount of liquidity injection by the SBP through OMO increased by PKR 2.0 trillion, while the stock of its loans (mainly refinancing schemes) to banks increased by PKR 740 billion. So the net amount of liquidity provided by the SBP to banks increased by PKR 2.7 trillion, while the government’s net borrowing from the SBP fell by PKR 2.0 trillion. The need for liquidity injection would have been lower had it not been for the PKR 2.2 trillion increase in CiC over the same period. On the other hand, there was a concurrent net increase in SBP’s foreign exchange reserves of $9.2 billion, which helped its NFA grow by PKR 1.6 trillion.

Rapid CiC expansion post FY2015 (initially triggered by the levy of tax on banking transactions of non-tax payers but subsequently fortified by increased scrutiny of banking transactions in general) is a structural drain on banking liquidity. CiC/M2 ratio that used to average around 22% before FY2015, has increased to over 29% in recent years. Had the ratio stayed at 22%, banking deposits would have been higher by PKR 1.7 trillion.

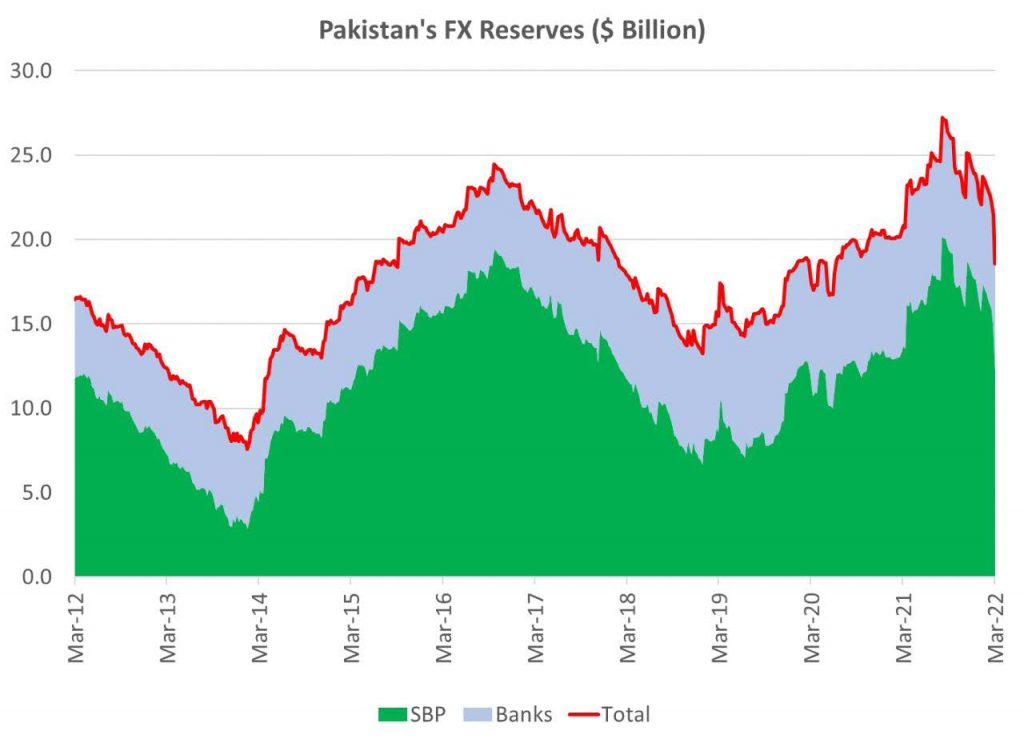

After two years of marked improvement in FY2020 and FY2021, helped by plummeting global commodity prices and travel restrictions during the peak period of pandemic, Pakistan’s external account has come under renewed pressure since the middle of 2021. SBP’s foreign exchange reserves have fallen by $4.3 billion in the past six-and-a-half months to under $16.0 billion by mid Mar-2022. Moreover, with ongoing domestic political turmoil, the focus has shifted away from preserving macroeconomic stability to protecting political capital. Unless the trend is arrested, the ongoing attrition of foreign exchange reserves shall continue to drain rupee liquidity creating more challenges for the government.

The latest amendments to the SBP Act not only bars incremental direct lending by the central bank to the government but also mandates that the existing stock of lending be retired at maturity. As of February 25, 2022, net fiscal borrowing from the SBP made up 53% of M0, while OMO injection formed another 32%, altogether accounting for over 85% of M0. With restriction on direct government borrowing from the SBP, the growth in M0 would need to come from:

a) Expansion in NFA, which in turn would require the country to run BOP surpluses, and/or

b) Increased stock of liquidity injection through OMO.

Perhaps the only time in Pakistan’s history when fiscal borrowing from the SBP fell ‘naturally’ was during FY2002 to FY2004 period when the country ran hefty BOP surpluses following 9/11.

Historically, managing the external debt maturities was the main challenge for the government. However, the amended SBP Act has made domestic debt management an equally bigger challenge especially during the periods of external account weakness. While the underlying intention of the amendment in SBP Act may be to induce fiscal discipline and external account stability, the deep rooted structural problems cannot be addressed by such restrictions.

Thus far, the SBP has been relying on weekly OMOs to inject liquidity with occasional use of longer duration (63 days) OMOs in Dec-2021/Jan-2022. Although theoretically there is no limit on the amount of liquidity injection by the SBP through OMOs, the banks have their own internal exposure limits on how much maturity mismatch they can run. Over Reliance on short-term liquidity injection by the SBP puts the Ministry of Finance in a vulnerable position in meeting its financing needs. While the amended SBP Act prohibits purchase of government securities in the Primary Market, it maintains the permission for the State Bank to buy these securities from the Secondary Market. Ideally, the SBP should have started secondary market purchases of government securities a while ago. However, it appears that the current IMF programme may be keeping the SBP from using this liquidity management tool. If that is the case, the IMF needs to be persuaded to let the SBP exercise the right to use all legitimate options for liquidity management. The IMF conditions should not take precedence over the law of the land. Notwithstanding the recently enhanced autonomy of the SBP, the financial system stability remains the most important common objective for both the SBP and the Ministry of Finance. The two critical institutions need to work collaboratively and not in disharmony.