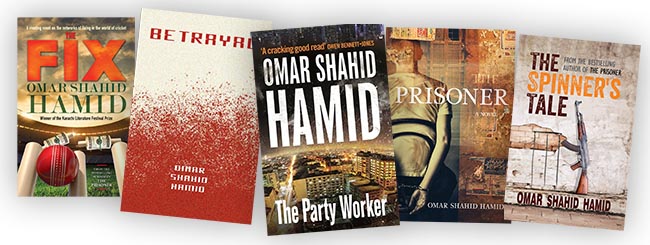

In less than a decade since his debut novel, The Prisoner, Omar Shahid Hamid, has made a mark for himself among the lovers of South Asian English-language Literature. Since his first novel, published in 2013, Hamid has written four more novels, which is kind of a feat in itself, given the fact that the author is one of the most decorated police officers in a crime and terrorism-infested country like Pakistan. But perhaps it is the very nature of his job which provides him much of the raw material to develop his works of fiction. One main question in the minds of many of his fans remains how he strikes a balance between his creative endeavours and professional life? After all, writing requires solitude, while for police work, one has to be a man of action.

It would perhaps be clichéd to say that Hamid has seen life in all its bitterness, crudity and challenges during his police job. He, himself, had to undergo a personal tragedy at a young age when his father, Shahid Hamid, a bureaucrat and managing director of the KESC, now K-Electric, was murdered in the teeming city of Karachi in July 1997. However, the young writer has not allowed his personal tragedy to reflect in his writing. And like his father, the professional work has put Hamid’s life in danger scores of time, and even now he remains on the hit-list of shadowy terrorist groups.

Hamid went for his undergraduate to University of Kent, Canterbury and did his first masters from the University College London (UCL). Then he did a second masters from the London School of Economics (LSE). His degrees are in law and criminal justice policy. A degree in criminal justice was a mid-career endeavour, more relevant to his profession.

Currently, Hamid is serving on an important assignment in Balochistan. Narratives Magazine talks to this prolific writer to shed more light on his literary undertakings.

Why do you write? And why fiction?

I think non-fiction is a difficult genre to master as a discipline. Obviously, one has to fact check, and look at it again and again. Fiction is much more creative and relaxing. You may say it’s cathartic. The other thing I’ve always felt is that by stating things in a fictitious setting, (one) can reach a far wider circle of readers. For instance, I got a lot of comments about my fist book The Prisoner which talks about police and law and order. Had I written a non-fiction book on how the police work in Karachi and across Pakistan, it would’ve been read by only a few. But when you write a novel, you can cater to a wider readership… it opens your works up to a lot more people.

To reach a far larger audience, do you intend to translate your books in Urdu?

I myself don’t have command over the Urdu language, but I was approached by a publisher and in fact the translation of my first book, The Prisoner, has just been completed. Hopefully, it will come out in the next four to five months. And that on its own will be interesting because if you publish in Urdu, it’s a whole different readership. I’m very curious to see the response. A lot of my colleagues in the police — especially from the lower ranks — often said that your books could be more accessible to us if they were in Urdu.

What kind of response do you generally get on your writings from your colleagues in the police?

Generally, it has been overwhelmingly positive. A lot of people have said that it’s good to convey the point-of-view of the police across, especially with the earlier books. But I don’t mean to write a propaganda piece. And if you read The Prisoner, especially, it doesn’t necessarily present the police in a positive outlook. It’s just a realistic perspective. People appreciate that they get a realistic kind of look into the lives of police officers in Karachi and in Pakistan.

When did you realise that you want to write, and become a police officer? Was it an epiphany of sorts?

I was never one of those people who, when they’re very young, had planned what they would want to do. It just happened. I stumbled upon it.

What’s your writing process like?

I like to write about different things. I like to keep challenging myself. My first three books were crime thrillers. Then I slightly diverted the path, and wrote about cricket match-fixing, which also revolved around the women’s cricket team, while my book Betrayal, is a spy thriller. The way I take up stories is that I may randomly come across something in a news clipping, it starts with an abstract idea and then I grow that abstract idea into a plot line and flesh out characters. Earlier, when I wrote my books, obviously I drew a lot from personal experiences and of my colleagues in the police. But now, as I keep writing, I keep expanding horizons and try to come up with new and interesting things to write.

How do you manage to be so prolific? You have written five books in a span of almost 9 years?

I haven’t written in the past five months or so, but generally I have been lucky enough to be prolific. I think it’s one of those things with me, since I’ve started writing it’s been cathartic; it has got to the point where I feel the need to write, and if I don’t write, it feels like something is missing. It’s like exercise, if you’ve not done it, you feel a little off. I don’t try to reserve a time slot for it but I do try to block time out for writing.

Writing, especially fiction, requires a certain sense of idealism, creativity, but then you are in the police force where your work is rooted in practicality. Do you think there is a conflict between the two roles?

I don’t necessarily think that you need idealism (to write). I don’t agree idealism is required for creativity. Creativity can have an effect due to your profession. I don’t think it’s mutually exclusive, in fact, I’ve always found that my job has helped to open up this world of stories for me that I keep using and fictionalizing. It constantly gives you new ideas.

But am I a realist and a gritty sort of a writer? I say yes. Perhaps you could also argue that it is a genre on its own. I’m willing to try out different themes. For instance, in The Fix, I went into a different direction, a female-centric book around match fixing. Even Betrayal is a departure from my previously published books on crime thrillers. Moreover, the book I’m currently writing is a political satire. Which would also be a departure from my previous books. I think changing things up in that way keeps you fresh as a writer.

There has never been a clash of my creative world with my professional world.

If you’re writing books about politics, crime, spies or a political satire, is there a need to be apolitical when writing novels, does it matter?

If you look at works of various novelists, I don’t think anyone has been apolitical, any of the great classic writers. So, I don’t think I can say that I’m apolitical. And I don’t think that has ever been a problem as far as writing is concerned, in that sense; if someone has a political point of view, I don’t think it’s a bad thing. In my case, if you ask me personally, I have always tried to portray those sort of worlds in which, whether it is policing or religious groups, political urban parties or whatever, I try to depict the world as it is or was. Some people have said that you have taken pot shots at the MQM in The Party Worker. My response to that; I don’t think that it’s taking pot shots. If you ask citizens of Karachi, who have lived in the city for the past 40 years or so, they will all say that these things happened. I also feel if you talk about writing about Karachi, as a novelist, and you leave out this incredibly massive party, you’re ignoring the middle years when looking at the history of Karachi.

I have noticed that your characters are in the shades of grey which is quite interesting.

You’re right, like in The Party Worker and in all my books, I try to paint my characters in greys.

One of the best compliments I have received is that we actually felt sympathy for the target killer and thought that was fantastic because it is very easy to portray him as evil incarnate but when you kind of put on these human shades on your characters, layers of humanity and emotions, the characters come out much more interesting. We understand where the character is coming from. You may not agree with it or their actions, but you may understand to a certain extent, sympathise.

That’s interesting, though your father was murdered by a target killer and that’s a very personal tragedy. How did you still manage to empathise with the target killer in your book?

Perspective and distance from the tragedy is important. Maybe I wouldn’t have been able to write, immediately after the incident had taken place. Therefore, I wrote these a couple of years after my father’s death — roughly after 10 to 15 years. And that has played a great role, but you’ve got to be able to look at people who may have totally different points of view and you’ve got to be able to consider where, what makes it tick. That comes a lot from my professional training as one of the jobs of a police officer is to be a mini-quasi psychologist. Because you’re dealing with all kinds of human beings, all the time.

Which character is closest to you, if you have to pick one?

Honestly, none. That has never been a consideration. I have never consciously modelled a character on myself. Unconsciously or subconsciously, elements of my personality may have been there in some characters, but never intentionally.

What was the most challenging book for you to write?

The most challenging book was probably, The Fix. Reason being, I pushed myself, because one of the criticisms which I had received was that in the first three books, female characters were not as strong as they should have been. That’s a fair point. Although, I would say that the first three books were about worlds where a strong female wouldn’t have naturally flowed because those worlds are male-centric.

Was there a different writing process when you were writing female characters?

That’s interesting, I didn’t think about it consciously. I don’t know a proper way of a male writer, writing about female characters but what I tried to focus on was their motivations and placing myself in their shoes.

Which books have inspired you, any authors that you look up to?

Before I started writing fiction, I didn’t read much of it. I was more of a history fan, narrative history, but I’ve always appreciated fiction writers who are able to transport you into a world of their own so when you’re reading their books, you’re in a zone where you can smell, taste and touch the characters they’ve created.

Do you think in this digital age, the mode of writing and storytelling has changed, would you like to meddle with different mediums perhaps?

Yes, it is quite challenging because you have to hold on to the attention of people who are used to reading things that are much shorter, but I think this is a challenge writers have had for a long time. Every time there is technological advancement, these questions come up for writers, will books be able to survive?

But I would admit, it is tough because you always have to be on your toes. One of my primary jobs as a writer is to be a good storyteller irrespective of the medium or the depleting attention span. If there’s a good story, it will resonate with the readers. People will read if the book is gripping.

There is a perception about South Asian writers that they are catering to a western audience and when they’re writing about Pakistan, there is a sense of superficial depiction of the country and its people. Your take please?

You know I don’t think that any writer starts out thinking that I’m going to write this for an audience for instance in London, but I do think, with reference to the Pakistani writers who write in English — the pioneers — they did and have spent a large portion of their lives in the West. So, they were kind of looking back at the Pakistan they knew of, from a distance. Therefore, I think this allegation arose; moreover, a lot of the younger lot say that these writers don’t resonate with us because these authors can’t relate with the world they’re living in. I think I’ve never done that; my writing is grounded in the world as it is today, therefore, I don’t think anyone has made that assertion about me.

Do you think a police officer can be neutral? Like they say about the KPK police that it’s an independent security force, portraying a positive image?

I won’t comment about the KPK police because I have never served there, I can’t speculate.

When you ask if a police officer is politically neutral, there are two things that need to be addressed. If you look at policing in a theoretical sense, it is a profession wherever you are whether you’re in Washington D.C, Lahore, or in New Delhi, you’re serving amidst the political sphere so there is always going to be a degree of politics in policing. The New York Police Commissioner is fundamentally an official who is selected by a political party, the Mayor, but when we talk about policing as being politically neutral, in our context, then we think in the operational sense which should always be the case. The police should not be bound by any kind of political considerations while investigating a case or carrying out their professional duties. Over the years, in our history, typical exigencies have been such that there may not have been a case which is 100 percent politically neutral.

Are you completely satisfied with how the police force is functioning in Pakistan? Are there any reforms that need to be brought about?

Police reforms are something that is almost constantly being spoken about but I think the nature of reforms is such that they can’t be constant since we as a society are continuously evolving. Pakistan is not the same way today that it was in 2001 when I entered service. I think it is very important to keep that process of reform on. With regards to the police performance, I can’t comment on police performance across Pakistan. Though I will say that a police force is reflective of the society that it is placed in whatever the positive or negative nature of that society may be. So, if you have a society that has systemic problems, you will have police forces having systemic problems. Can they do better? Sure. Absolutely.