COVID-19 compelled governments all over the world to refocus on health, agriculture, and social protection. Health and social protection are quite understandable, let me explain why agriculture. During the lockdowns, when international travel, borders, and cargo shipments were restricted, only countries self-sufficient in agriculture could ensure food security to their people. Covid is not over yet and so the focus on agriculture remains.

In our case, agriculture was always important. People my age can recall that we grew up reading, “Pakistan is an agrarian country,” and “Agriculture is the backbone of Pakistan’s economy.” However, during the last two decades the share of agriculture in Pakistan’s Gross Domestic Production (GDP) saw a gradual decline. In fiscal year (FY) 2020-21, this share was 19.2 percent of the GDP.

Despite losing its share in GDP, agriculture is still important for us, for food security and livelihoods. It provides employment to around 38.5 percent of the labour force. More than 65-70 percent of the population depends on agriculture for its livelihood. Moreover, our export basket is predominately agro-dependent.

Even without lockdowns, Pakistan needed to focus on enhancing the production of basic food commodities, not only to improve food security, but also to balance the current account deficit through import substitution of food commodities.

After the 18th amendment in the constitution of Pakistan, agriculture was devolved to the provinces. However, once again the federal government is taking a keen interest in the agriculture sector and trying to support the provinces in bringing about agricultural transformation.

Before we go to the future of the agriculture sector in Pakistan, let us have a quick glance at where we stand today. Pakistan is one of the few countries among its peers that despite COVID-19, had a growth in GDP of 3.94 percent, during the Fiscal Year (FY) 2020-21.

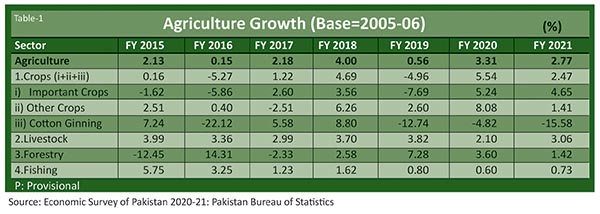

The agriculture sector played an important role in this growth. It grew by 2.77 percent against the target of 2.8 percent. The growth of important crops (wheat, rice, sugarcane, maize and cotton) remained 4.65 percent in FY 2020-21. In fact, the production of major ‘Kharif’ crops (which are sown in April-June and harvested from October to December) such as sugarcane, maize and rice indicated considerable improvement compared to last year and surpassed the production targets. Wheat, the most important crop of ‘Rabi’ (sown in October-December and harvested in April-May), showed a growth of 8.1 percent and reached a record high production level of 27.293 million tonnes. However, the cotton crop in 2020 did suffer, mainly due to a decline in area sown, heavy monsoon rains and pest attacks. In the last fiscal year, cotton production reduced by 22.8 percent, to 7.064 million.

Likewise, livestock having a share of 60 percent in agriculture and 11.53 percent in GDP, achieved growth of 3.06 percent during FY 2020-21 (Table 1).

Current numbers, amidst the pandemic, are impressive. However, the actual potential is much higher than these numbers. An average farmer’s per acre yield in Pakistan is 29 maunds (40 kg) for wheat, 50 maunds for coarse rice, 57 maunds for maize, 18 maunds for cotton and 656 maunds for sugarcane. Compare these numbers with a progressive farmer in Pakistan, who gets for each acre 45, 80, 80, 35, and 950 maunds of wheat, coarse rice, maize, cotton, and sugarcane, respectively.

Why is there such a yield gap among farmers, farming in the same country under similar agro-climatic conditions? Preparedness of progressive farmers against Climate Change (water scarcity, water productivity, increased temperature, intense but shrunk monsoon) i.e., climate-smart agriculture is one factor. However, the other factors that favour progressive farmers, in no particular order, include timely availability/affordability of inputs especially certified seeds, fertilizers and pesticides; their access to research, development, and extension services; farm mechanisation; and adequately trained human resources etc.

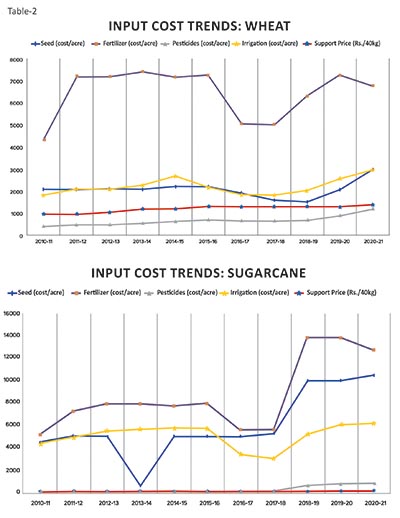

To reduce the yield gap between a conventional and progressive farmer, therefore, requires addressing the factors hindering the crop productivity of a conventional farmer; i.e., timely provision of quality inputs at an affordable price (the figures below for wheat and sugarcane crop reveal how the input cost has increased); providing them with research-based extension services, enabling them to adopt climate smart and precision agriculture techniques, improving their access to farm equipment, and developing their strong forward and backward linkages with the secondary (industrial) and tertiary (services) sectors.

The federal government is trying to address most of these factors through the “Agriculture Transformation Plan” (ATP) approved by the Prime Minister and being implemented by the federal and provincial governments under his direct supervision.

Implementation of the ATP is already underway. To expedite the varietal approval system for unavailable technology and to weed out fuzzy seed companies, amendments have been made in the Seed Business Regulations Rules, 2016. Likewise, a track and trace system is being introduced to establish seed authenticity for farmers. These initiatives would help in improving the seed quality of major crops.

The ‘Kisan Card’ in Punjab, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, and Balochistan, and ‘Hari Card’ in Sindh are being rolled out to provide a subsidised supply of farm inputs to targeted beneficiaries through the use of data and digital technology.

According to a recent estimate, in Punjab province for every 10,000 acres, there are 140 tractors, 102 cultivators, 14 rotavators, and 5 disc harrows. To foster farm mechanisation, provision of subsidised farm equipment under ATP and the Prime Minister’s National Agriculture Emergency Programme have been approved and spadework is being done in this regard.

One of the manifestations of climate change is a reduced supply of water. Our agriculture is mainly dependent on the Indus Basin, which is being inefficiently managed. To improve water efficiency, lining of old watercourses, use of laser levellers for land, and soil moisture meters are being provided under the ATP.

To provide customised and timely advice to farmers, ICT-based interactive extension services are being introduced in Punjab. Other provinces hope to follow soon. Cellphone based precision agriculture is being practiced in India and Kenya for cotton, sugarcane and cumin crops. Attempts are being made to replicate this model for our major crops.

To improve the quality of agricultural research, existing public sector research centres in Punjab are being converted into “Centres of Excellence” for sugarcane, rice, wheat, and maize. These centres are being turned into autonomous bodies, governed by independent boards of governors, and a market-based incentive mechanism is being introduced for researchers. Research centres in Turnab, Mingora, Quetta, and Mirpur Khas are also being upgraded.

Timely availability of capital had been a major challenge for farmers, especially small to medium farmers. According to a recent report, most of the farm and off-farm agricultural credit ends up in a few hands in Lahore, Karachi and Islamabad. A farm credit of Rs. 292 billion was provided to 2707 borrowers in these three cities, compared to Rs. 345 billion provided to 146,1899 borrowers in the rest of Pakistan. This skewed distribution requires a paradigm shift in the agri-credit market. This is being introduced through different schemes initiated by State Bank of Pakistan and commercial banks under the Kamyab Pakistan Programme.

The list of interventions under ATP is quite long, including olive deepening, shrimp farming, and cotton revival initiatives. There are different interventions to reduce post-harvest losses through promoting warehouses, silos, and the introduction of an “electronic warehouse receipt regime” by different commercial banks.

The crux of what I have mentioned here is that agriculture in 2022 is dependent on how quickly our farmers adapt to climate change and shift to climate-smart agriculture. It is dependent on how best we use ICT based and cellphone based services to customise our extension services. It is dependent on timely availability, at an affordable rate, of key inputs including quality seeds, fertilizers and pesticides. The productivity enhancement needs to be followed by a reduction in post-harvest losses and providing protection to farmers against product glut in the harvesting season; hence the future of agriculture is dependent on modern storage facilities. And finally, it depends on rewarding research that may get translated into action.

A cursory look at the ATP reveals that most of the above mentioned aspects are being addressed in the plan. The federal government has provided a policy framework for agricultural development in Pakistan. It is going a step ahead and sharing the cost of many of the proposed interventions with the provinces. The Prime Minister is taking a keen interest in its implementation and taking regular follow-up meetings on its implementation.

The buck stops at the provincial governments. The more interest they take in uplifting the agriculture sector, the more food secure Pakistan would be. We hope to hear some good news on the agricultural front in Pakistan in 2022.

The writer is Executive Director, Sustainable Development Policy Institute.