Where is the Afghan peace process headed? The euphoria generated at the signing of the peace agreement between the US and the Taliban on February 29, is now giving way to the stark reality that the path to peace in Afghanistan is full of pitfalls. From the very beginning, there have been hurdles along the way. One of the major agreements concerning the prisoners’ swap was mired in controversy because of Ashraf Ghani’s reluctance to release 5000 Taliban prisoners. It took more than seven months and a considerable amount of nudging from the US and Pakistan before Ashraf Ghani’s government and the Taliban finally agreed to the prisoner swap and resumption of intra-Afghan dialogue. The dialogue resumed on September 12 but this time it got stuck on modalities. Unfortunately, there is no agreed agenda for the talks; moreover, there is no ceasefire in place, as a consequence of which there is unnecessary death and destruction on both sides. The country remains hostage to the warlords, rent-seeking government officials and external spoilers who want to keep the pot simmering.

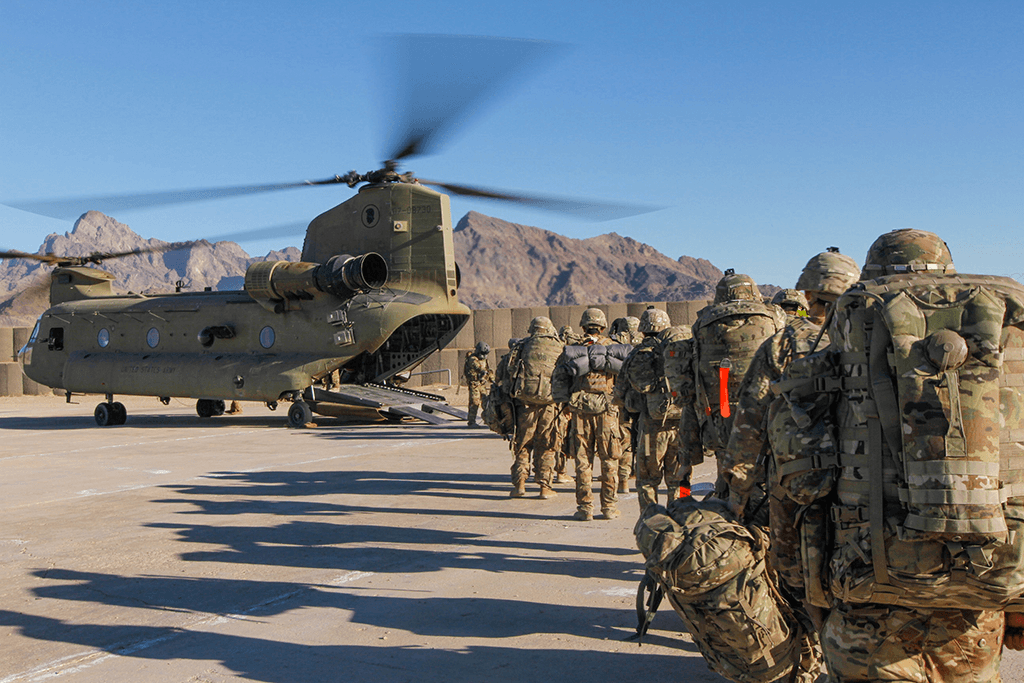

The peace process is pitted against many odds which hamper a smooth transition from the present war-like conditions to peace, as the nightmare of a civil war looms in the not-too distant future. This is all linked to the timing of the American withdrawal. President Donald Trump wishes to see the American troops return home before Christmas. However, his National Security Advisor Robert O’Brien maintains that the United States intends to reduce its troop levels in Afghanistan from 5,000 to 2,500 by early 2021. The Pentagon and CIA may have different axes to grind, which was echoed by Gen. Mark Milley, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, when he said that the agreement reached with Afghan and Taliban officials to leave Afghanistan was “condition-based,” and that the United States would “responsibly” end the war.

From the international perspective, American-led military engagements have started giving diminishing returns. The operations that have been carried out in Afghanistan since 2015 do not enjoy international backing. A Bilateral Security Agreement (BSA) between the Afghan government and the US was signed in 2014 that allowed American and NATO troops in Afghanistan to stay on in an advisory role to oversee the Afghan National Security Forces’ (ANSF’s) training and operations. The BSA exempted American and NATO troops from prosecution in the International Criminal Court (ICC). This was also the period when then President, Barack Obama, began bulk withdrawal of US troops from Afghanistan after an unprecedented surge in 2010. Consequently by the end of the Obama presidency in 2016, the US troop level came down from 100,000 to 16,000. Being a businessman, what President Trump is doing is simple economics — but with substantive political gains. He has assured his voters that he would save $ 50 billion per annum from the wasteful war and bring the soldiers back home. He has also proven his point that after the signing of the agreement with the Taliban in February this year, no American soldier has died in Afghanistan.

It is now becoming clear to the overwhelming majority in Afghanistan that the Americans are finally leaving. This could be disturbing for the Ashraf Ghani government, as the American troops’ withdrawal may change the status quo for him and the Taliban may emerge as a dominant force, either through a smooth process of intra-Afghan dialogue or through military means — a fact acknowledged by the Americans and European observers, even if grudgingly. In a way, by announcing withdrawal, the US has started losing ground among various Afghan factions, although they would continue to owe allegiance to the Americans till the time their pockets are lined and they enjoy a walk in the corridors of power. But at the same time, they would weigh their options to stay relevant.

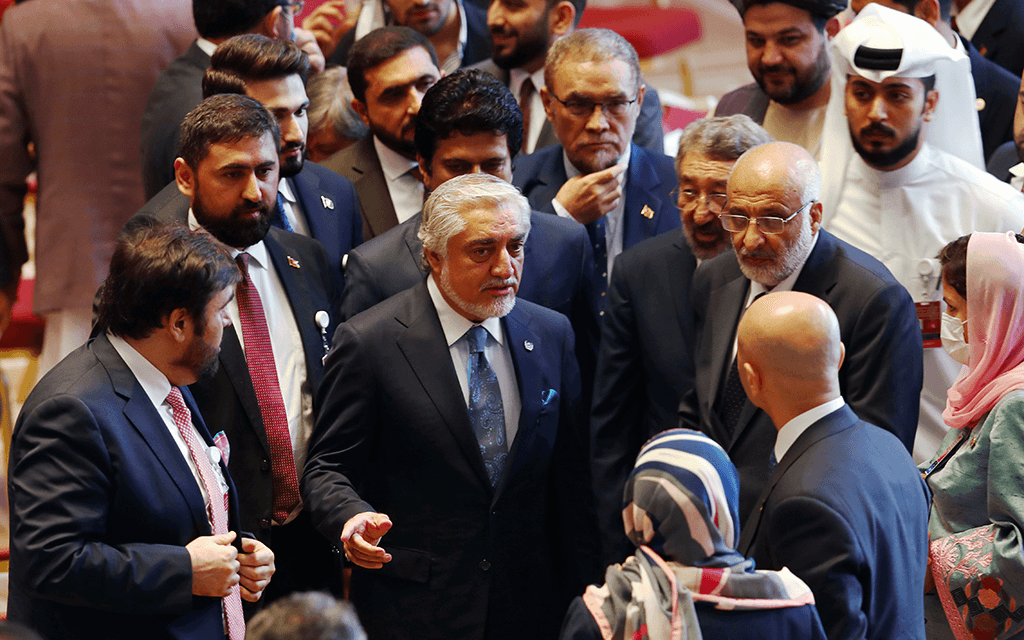

As for the intra-Afghan dialogue, again, there is a big gap in the goals and objectives of the stakeholders. Disagreements over the agenda of the dialogue is keeping the whole process in a state of paralysis, despite friendly counselling by the US and Pakistan. Prima facie, the Dr. Abdullah Abdullah-led government delegation comprises various ethnic and religious factions, who approximately represent the entire political spectrum of Afghanistan, even though some of the ethnic and religious groups may not see eye to eye with each other. On the Taliban side, it is almost a monolith with disciplined cadres owing allegiance to the leadership of Mullah Haibatullah Akhundzada. If the dialogue process is successful it would most likely culminate in an interim government, leaving President Ghani’s political future in limbo, which would probably be unacceptable to him and his associates.

Parallel to the snail-paced intra-Afghan dialogue, there are reports that the Taliban are reaching out to various ethnic and religious groups, which means that as a second option they will individually strike deals with the prospective stakeholders and try to marginalise the existing power-brokers linked to the government. This was further corroborated by the former prime minister and leader of the Hizb-e-Islami Afghanistan, Engineer Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, while addressing the Institute of Policy Studies (IPS) in Islamabad on October 21. He said that his party had separately initiated talks with the Taliban to chalk out a future course of action.

The Taliban have also reached out to the regional countries to put across their point of view, especially Iran, China, Russia and the neighbouring Central Asian States (Tajikistan, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan), to assure them that they are not pursuing an outward-looking agenda and that they are not in cahoots with Al-Qaeda or Daesh. In fact, the Taliban’s fierce fight and successes against Daesh/ISIS have been acknowledged by the American administration and international observers, which strengthens their credentials as an effective bulwark against the Al-Qaeda/Daesh threat and lessens the likelihood of Afghan soil being used by these extremist Islamic groups.

The current scenario may not offer much optimism but there is a glimmer of hope. War fatigue among Afghan’s warring factions and international partners may force the stakeholders to opt for peace. As a first step, the Taliban should announce a ceasefire, while the government side should be prepared for a national government to give peace a chance. Secondly, external actors should stop using Afghanistan as a competing ground to settle scores or use Afghan territory to destabilise other countries. Thirdly, the UN should step forward to ensure that rehabilitation and reconstruction activities are carried out in a comprehensive manner so as to rid the country of the narco-business, and create conducive conditions for the return of Afghan refugees to their homes. A peaceful Afghanistan can truly serve as a bridge between Central and South Asia, with unprecedented prospects of progress and prosperity for the entire region. However, the onus for peace lies on the Afghans.