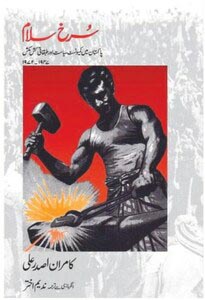

Author: Kamran Asdar Ali

Urdu Translation: Nadeem Akhtar

Publisher: Maktab-e-Danyal

Pages: 459

Price: Rs. 950

“A January afternoon at the house, a few minutes’ walk from the tube station, an elegant woman welcomed me at the doorstep with a big smile. Perhaps I reminded her of someone she knew during her Lahore days. After pleasantries, she asked me if I would like something, but the sentence was left unfinished. I was not sure whether it was an invitation for tea or lunch. It was one in the afternoon and I imagine she was offering me a cup of soup.

‘What do you have,’ I asked.

Well, I can offer you scotch or gin,’ she replied.

I was a bit taken aback. I had come prepared for an interview and a drink on the rocks was not my idea of focusing on the topic. I declined, she smiled again and just said. ‘All Pakistani communists started drinking before noon and they loved scotch, neat.’ This was a delightful comment, welcoming and absolutely true. After all, she had known them all!”

When a researcher, with a plethora of foreign degrees, showcases a superficial, traditional, and narrow-minded reading of Communists, it raises a question on the author, Kamran Asdar Ali’s ideological and intellectual might. The problem actually lies in his absolute agreement with an ill-informed, gross misrepresentation of Pakistani Communists.

Presently, neither does the Communist Party exists nor the card-holder Marxists. However, for decades rivals accuse many comrades of being ‘atheists, immoral, and drunkards.’ And the aforementioned anecdote reinforces this allegation.

When Surkh Salam — originally written in English — was translated in Urdu, I read it keenly, and the book took me down memory lane. It not only reignited memories but the history of leftist politics swept my mind.

Countless books have been written on Pakistan’s founding party, the Muslim League and its leader Quaid-e-Azam Muhammed Ali Jinnah, but we find a paltry amount of books published about the anti-Muslim League parties, nationalists, and progressive political forces. There are scattered accounts about the parties that opposed the Muslim League, such as the Awami Muslim League, the Awami League, the Azad Pakistan Party and the National Awami Party, though a large amount of memoirs and biographies have been written about the ebb and flow of the Communist Party of Pakistan (CPP) and leftist movements in the country.

The Rawalpindi Conspiracy Case, which led to the ban on the Communist Party, has been captured terrifically by Major (retired) Ishaque. Abd-ur-Rauf Malik, Sardar Shaukat Ali, Tufail Abbas, Abdullah Malik and Professor Jamal Naqvi’s writings, also provide a lot of information and illustrate divisions within the Communist Party.

But at least this student of politics hasn’t come across any book that could be called a comprehensive recollection of the CPP’s history, even though, the Indian Communist Party’s history has been complied in various volumes.

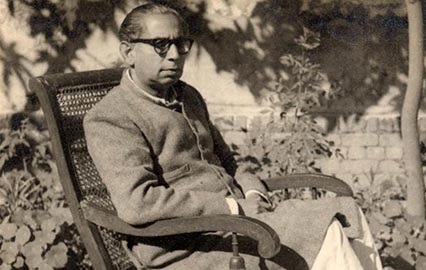

In Pakistan, it was undoubtedly, Syed Sibte Hassan, a pioneer Party card-holder, who could have written an accurate history of the Communist Party since his works including, Musa se Marx Tak, Maazi Ke Mazaar, Naveed-e-Fikr, hold biblical status in the realm of ideological texts. If only, he had penned it, students and comrades like me would have gained an authentic understanding of the challenges, toils and struggles, as well as mistakes of the Pakistani Communists, which could have been passed on to the coming generations.

I won’t hesitate to claim that since 1970, I have had the honour of staying in the company of a long list of Marxists whose names I must mention: Syed Sibte Hassan, Dr. Sher Afzal Malik, Dr. Haroon Ahmed, Dr. Muhammad Sarwar, Sobho Giyan Chandani, Minhaj Muhammad Khan Burna, Mairaj Muhammad Khan, Sher Muhammad Marri, Afrasiyab Khattak, Prof. Jamal Naqvi, Abid Hasan Minto, Abdullah Malik, Prof. Amin Mughal, Dr. Eqbal Ahmed, and Dr. Feroze Ahmed. And some of these comrades had never touched liquor, or even if others did, it was only after sunset.

It’s an interesting coincidence that the Urdu version of this book has been published by Maktab-e-Danyal, established by Malik Noorani, who was a close friend of Sajjad Zaheer and a sympathiser of the Communist Party. Malik Noorani’s wife was one of the leaders of the party’s Anjuman-e-Jamoohriat Khawateen. When Sajjad Zaheer went into hiding, he would stay at Malik Noorani’s place. Now Noorani’s daughter, Hoori Noorani, runs Maktab-e-Danyal. She might remember that in her childhood, comrades from the National Students Federation (NSF), including myself would visit her home — an apartment at the Club Road — after day-long sloganeering. We would have tea there, then dinner and sometimes would stay for study circles conducted by senior comrades till late at night.

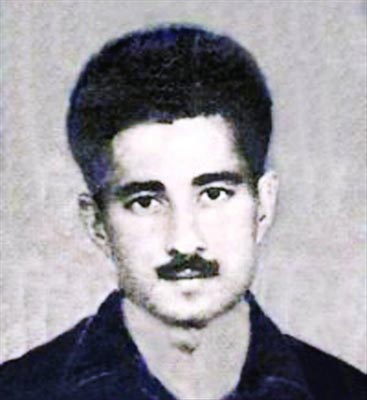

Moving on, I do feel that I might have been slightly unfair to Kamran Asdar and his treasure trove work but how can I ignore and let go the brazen allegation of John Afzal, whose husband, Afzal Khan, was arrested for a few years after the ban on the Communist Party. Later he fled to London. This accusation blatantly downplays the prolonged ideological and intellectual struggle of a large number of comrades and activists, who served long sentences; all of them put their future and families at stake and some turned into cerebral patients or died wretched deaths, while never having indulged in a luxury such as drinking alcohol. One of the stars of the Communist struggle in Pakistan, Hasan Nasir, was tortured to death.

In the beginning of the book, Kamran Asdar Ali shared a note of thanks spanning 11 pages. One must admit that the author conducted extensive research and a large number of interviews in various cities for days. The most important chapter is on the events from 1940-47 and then up till the ban of the Communist Party in 1954. Most importantly, he mentions the Calcutta Congress, where details related to the Communist Party have been made public for the first time.

Another extremely important chapter is the one in which the author describes Hasan Nasir’s murder in Lahore’s Shahi Qila.

Research on the Communist Party is an uphill task. After the formation of the party in Pakistan in 1948, comrades from Pakistan and those coming from India, were on the run and in hiding (‘underground’ as it was dubbed in the party circles) for years.

The major reason for the ban of the Communist Party was the Rawalpindi Conspiracy Case, on which Faiz Ahmed Faiz wrote a couplet:

Woh baat saare fasaane mein jis ka zikr na tha

Who baat unko buhat nagawar guzri hai

Surely, meetings between the Communist Party members and the military officers were not mere cocktail parties, it was decided by the Party’s Central Committee that Syed Sajjad Zaheer would meet General Akbar Khan and his colleagues, who were extremely upset with the way the Muslim League government agreed to the ceasefire in the disputed Kashmir region. This displeasure made sense as under General Akbar Khan, soldiers and tribal volunteers were only five kilometres away from Srinagar, which was waiting for them with arms wide open. It remains mired in controversy whether Pakistan’s then incumbent government, could have pushed in that direction, but it is a fact that a statesman like Jawaharlal Nehru rushed to the UN in panic, while the Maharaja of Kashmir ran away to Delhi.

The Muslim Conference’s leader, Sardar Abdul Qayyum, confessed in a meeting with the scribe that it was the first and last effort towards freeing the occupied territories but British officer Gracy and his counterparts pressurised Pakistan’s civilian and military leadership to compel General Akbar Khan to recall the army and tribal volunteers from the Kashmir mission. It is also intriguing how the Pakistani civilian and military leadership — propped up by the United States — could ignore the conspiracy concocted by the Communist Party and the military officials.

After imprisonment and acquittal of comrades post Rawalpindi Conspiracy Case and especially Communist Party’s Secretary General Sajjad Zahir’s exile to India in 1955, even if there was a party framework, Kamran Asdar Ali’s book doesn’t shed light on it. The author, despite having researched for decades, couldn’t succeed in mentioning who held the position of the acting secretary after Sajjad Zaheer’s exit and even if the Party’s organisational structure didn’t exist, who gave others the right to run the Party clandestinely in Sindh, Punjab and the former NWFP.

Let’s accept that due to strict restrictions and hardships, the entire Party’s network and those assuming responsibilities, were working in a clandestine manner. However, after General Zia-ul Haq’s Martial Law, the unannounced ban on the Communist Party was lifted and the comrades who were on the run for almost three decades, began their activities openly. Comrades such as China-leaning Tufail Abbas, Mairaj Muhammad Khan and Moscow-leaning Professor Jamal Naqvi and Jam Saqi could have been interviewed for an accurate account of those times.

The CPP’s ‘underground’ history cannot be written without conversations with eyewitnesses to the struggle. It is also necessary to consider whether those interviewed are genuine and committed sources or not. Sorry to say, Kamran Asdar Ali interviewed almost 200 comrades, their children and their sympathisers, but many of them have either been deviants or considered as dubious sources.

Syed Sibte Hassan’s book Mughnie Aatish-e-Nasaf: Sajjad Zaheer, complied by Jaffer Ahmed, has honestly articulated the Communist Party’s formation in 1948, its ban after the Rawalpindi Conspiracy Case, the release of its Secretary Sajjad Zaheer in 1955 and then his departure to India. This is because Syed Sibte Hassan’s writings are considered authority amongst comrades. Surely, Kamran Asdar Ali benefitted from this piece of work, and yet he did not mention what happened to the unfortunate party and its depleted comrades later. He’s perhaps unaware that the real conflict started after Sajjad Zaheer left for India.

After Hasan Nasir’s death in custody there was an atmosphere of fear, due to which many of the Party’s card-holders either left the country and lived cushioned lives abroad or they compromised and became informants and self-professed leaders of the Party.

The Party’s division became evident in 1967-68 and this writer — then in his first year of university and part of the Moscow-leaning group — was an eyewitness to these events and the formation of factions.

The situation of the China-leaning faction of the party was clear. When a large-scale people’s movement comprising students and labour emerged, the majority of its leadership and followers either joined Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s Pakistan People’s Party (PPP) or the National Awami Party’s (NAP) Bhashani group.

The yesteryear leaders of the Communist Party’s student wing — the Democratic Students Federation (DSF) — Dr. Muhammad Sarwar, Dr. Haroon Ahmed, Dr. Adeeb Rizvi and then Dr. Sher Afzal Malik and Dr. Mehboob, had completed their political innings in the 1970s. However, their student protégés had taken hold of the DOW Medical College’s Moscow wing.

Although it is a misfortune that the Moscow-leaning party was divided into two. Dr. Sher Afzal Malik, Dr. Mehboob and B.M Kutty had reservations against the party’s original heirs, such as, Imam Ali Nazish, Professor Jamal Naqvi and Sain Azizullah. Frankly, the true Moscow-leaning party was that of Imam Ali Nazish and Jamal Naqvi.

Recently, I learnt from Juma Khan Sufi’s — the Communist Party’s representative who stayed in exile in Afghanistan for years — book Faraib-e-Natmam that Moscow had given Imam Ali Nazish’s party the official status, which was being run by Professor Jamal Naqvi.

After the PIA hijacking episode in 1980, remnants of the Party were treated cruelly, leading to Nazeer Abbasi’s death and its two main leaders, Jamal Naqvi and Jam Saqi, being imprisoned for six years. Both Naqvi and Saqi have written about why and how they quit the party in their books.

In the end, Kamran Asdar Ali must be applauded for his great effort in compiling the Communist Party’s history up till 1955. However, the infighting, division, and dilution of the party merits a second and updated edition of the book.