Almost 80 percent of the people of Pakistan do not have the means to provide a better future for their children. It’s a luxury that can be afforded by only about 15-20 percent of Pakistanis. This unfortunate situation exists because the economic objectives of the 21st century cannot be achieved by holding onto the development paradigms of our Mughal past.

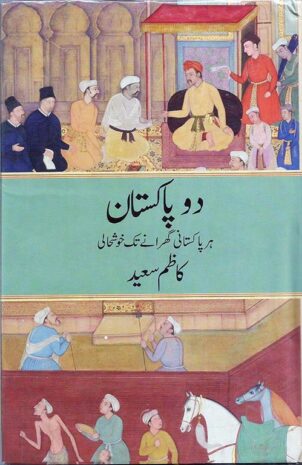

Based on this premise, Kazim Saeed’s Dou Pakistan: Har Pakistani gharane tak khushali (Two Pakistans: providing prosperity to every Pakistani household) clearly identifies the direction the country needs to take and the targets it must set for itself in order to ensure prosperity to every household by 2047.

The theme of this 600-page book may seem ambitious to some, but it is doable. The simple manner in which the topics have been broken down makes it an easy read, even for those with no background in economics. The topics are laterally compartmentalised, with each one flowing into the other so that the thread of one’s thoughts and understanding is not lost. Very few experts have attempted to broach such a comprehensive subject in Urdu, which makes it worth reading all the more.

Upon returning to Pakistan after having spent many years working on economic development abroad, Kazim Saeed found many young Pakistanis asking him basic questions about economic development and poverty eradication. As a practitioner in this field, he knew how many non-western countries had already achieved these goals over the last few decades. The answers were already out there but Kazim Saeed felt that those answers needed to be presented to Pakistanis in the context of their own realities and in a way that was easy for them to comprehend.

Dou Pakistan takes the reader back and forth between the Mughal era and present-day Pakistan, making it easier to understand the basis of our economic woes.

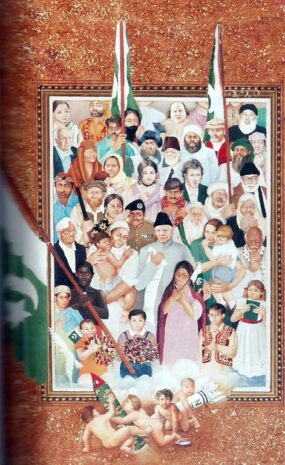

From one off-the-beaten-track village in Sindh to another in Balochistan all the way up to Gilgit Baltistan, every poor family has the same story and holds the same belief that only the rich get richer, while poverty is written into the fate of the poor the day they are born. Dou Pakistan defies this very belief, writes Kazim Saeed.

Following several decades of diverse research, the author has identified and shortlisted four elements that play a pivotal role in improving the chances of generational prosperity in Pakistan: inherited wealth, quality education, permanent, dependable means of income and access to influential people. Unfortunately, without these four elements in place, our economic structure alone is not equipped to help people change their fate.

Employing his impressive background as an economist and his keen interest in Mughal history, the writer draws parallels in terms of persistent economic disparity between the Mughal era and present-day Pakistan. The walls of the Mughal forts also served as economic barriers for those wanting to change their lives. Now, like then, a relatively easier way to scale the wall is to acquire a government job or join the armed forces.

Poverty alleviation and equitable development were never a priority in Mughal society, and even though these goals are quite achievable today, Pakistan lags behind because our society and economy continue to be structured along Mughal lines. Dou Pakistan discusses how countries outside Europe and the US, like China, Malaysia, Brazil, South Korea and Turkey, have successfully tackled poverty. But Pakistan has not. There are still two Pakistans, one that prospers inside the fort wall and the other that struggles to survive outside.

In an attempt to understand and address generational poverty, the harsh reality of hunger is mostly ignored, even though it is the basis of the very concept of poverty. Everyone understands hunger but perpetual hunger is a condition that is hereditary and a difficult cycle to break even today. Dou Pakistan deals with this issue not only through statistics but also in terms of how it an impediment to our evolutionary growth. Every ninth person in this world suffers from perpetual hunger. The relevance of this book comes from the fact that the centre of perpetual hunger today is not Africa but South Asia, which is home to one-third of the world’s hungry: some 20 crores in India, 4 crores in Pakistan and 2.5 crores in Bangladesh.

The crux of the issue has been heartbreakingly summed up by the people of Mirpur Khas, also known as ‘the City of Mangoes:’ “The rich-poor disparity is such that for days we go without food; it first forces us to become thieves or defaulters and finally criminals.” Citing hunger-alleviation strategies adopted by countries like Brazil, China and Turkey, Dou Pakistan provides case studies of how this cycle of hunger, illness, mental and physical growth, illiteracy and malnourished births can be broken.

Population is another sector that reflects two deeply entrenched Pakistans. Today, 270 children are born to 100 women in the top 20 percent of families, which is quite at par with the well-off classes in developed East Asia. But in the remaining 80 percent of families in Pakistan, 100 women give birth to 420 children, comparable only to the most under-developed regions of Africa. Pakistan has so far failed to get a grip on population complexities, may that be an honest census or the golden ratio of population and a healthy work force. The book looks into successful examples of other Muslim countries like Indonesia, Iran and Bangladesh, and the impact of fertility rates on the distribution of resources.

The modern world’s first social security system was established by German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck in 1883. He was in no way a socialist or communist. In fact, Bismarck was a conservative leader and his sole purpose behind the provision of social security was to make German manpower the most effective in Europe. Against this backdrop, the section on human resource deals with how prosperity in the 21st century will depend on technology based on modern sciences and not traditional productivity. In the fast-changing economics of the 21st century, illiteracy will prove to be more than a disability. And without social security measures in place, Pakistan will lose out on human capital.

The most effective way to ensure prosperity is through higher education. In Pakistan just six percent get that chance. Our focus on literacy more than education continues to be a reflection of Mughal priorities. Establishing equal-opportunity education is possible. Despite similar complexities and hurdles, several contemporary countries have achieved universal education. The book takes a deep dive into how these impressive targets were achieved.

Mughal Emperor Shahjahan’s beloved wife Mumtaz Mahal gave birth to 14 children, of which only seven survived. The rest died by age five. Most mothers in 21st century Pakistan undergo similar pain. The problem is, unlike the education sector, there’s no authentic method to gauge the annual performance of the health sector. Things which cannot be measured cannot be effectively improved. That’s the way of the world and it’s one of the biggest hindrances in evaluating the resources required to provide quality healthcare services to those living outside the wall. The ninth edict of Emperor Jahangir was about the establishment of royal hospitals in big cities run on royal revenue. Dou Pakistan discusses how the country’s traditional health system is still run along the same lines, with no facility for the poor living in rural areas and compromised healthcare in urban centres due to lack of resources.

In identifying and highlighting the solutions to bringing down the wall that divides Pakistan, this book acknowledges the work of world-renowned social scientist Akhter Hameed Khan, who advocated community participation in rural development. He was inspired by the three principles of Friedrich Wilhelm Raiffeisen, the German pioneer of cooperatives. Akhter Hameed Khan believed that organisation, making assets via savings and promotion of skills were absolutely necessary for the growth of the poorest. He proved the effectiveness of these principles through his Comilla Model. Strategies based on these principles have been successfully implemented in countries like Japan, Taiwan, Israel, The Philippines and South Korea.

Unlike the Mughal times, economic strength today is derived from productivity, not tax generation. Dou Pakistan explains in detail the means to achieve prosperity in this time and age, and offers takeaways from success stories from around the world. After all, the strategy to become a champion must be learnt from a champion, says Kazim Saeed.