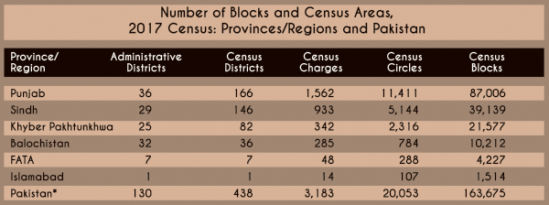

The results of the 2017 census have remained controversial ever since they were released. Objections have not only been raised by all the political parties of Sindh, but by the electronic and print media, by civil society as well as scholars, about a gross undercount of Sindh’s population in general and of Karachi in particular. Apparently, for that reason, the Council of Common Interests (CCI) has yet to reach a consensus on validating the results. Even the Chief Justice of Pakistan is on record suggesting that Karachi’s population is perhaps twice that reported in the provisional results. Prior to the 2018 elections, the Supreme Court had taken the stand that since the census results were provisional; therefore a constitutional amendment was needed, as elections could not be held without official notification of the results. Therefore, prior to the 25th amendment, an agreement was reached in the Senate, duly signed by the leaders of all political parties for a 5 percent recount to be supervised by a neutral Census Commission, consisting of qualified and experienced demographers. Consequently, the Census Commission consisting of three prominent demographers was notified by the government in January, 2018. In its first meeting on the basis of advertisements in major newspapers by the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics (PBS), several firms were shortlisted for conducting the 5 percent recount by a third party. The Census Commission also invited several demographers from the country, and most voiced their doubts about the census results. Unfortunately, the Census Commission called off the second meeting, and no further meetings were held.

One of the wheels of democracy which helps a country’s smooth functioning is counting the appropriate number of people all over the country, so that they could choose their representatives on the basis of one man one vote. Besides, the census also provides relevant data at national, provincial and local levels for proper planning. Accordingly, the 1973 Constitution mandates conducting a census every ten years, which could become the basis of demarcating constituencies at the national, provincial and local levels, besides determining the share of each province through the National Finance Commission (NFC) award. However, since then, only the 1981 census could be conducted on time, with proper planning and under the supervision of experts. The next census was conducted after a delay of 17 years and the most recent one, after a delay of 19 years.

Census results are never perfect, and thus under or over-counting of people does happen in both developed and developing countries. This is determined by a post-census survey, by re-visiting about 2 percent of the sampled census enumeration blocks. For example, in the 2011 census, about 1.5 percent people were undercounted in Australia, 2.5 percent in India and 4 percent in Bangladesh. Demographers in the advisory committee for the 2017 census had strongly recommended a post-census survey and they did not advise checking the CNIC of each household member. However, PBS did not accept these recommendations. According to a report prepared by the United Nations Observer Mission, which was present during the census exercise, the CNIC of each household member was checked, verified and recorded and the enumerators relied on information available on the CNIC. Therefore, as a result of the de jure method used in the census, it is likely that household members having a different address on the CNIC were later allocated to their original place of residence. Besides, due to the requirement of having a valid CNIC to be counted in the census, those who did not possess one and particularly aliens were not included. Perhaps for that reason, the reported population of Sindh, particularly of Karachi, is much below expectations.

To evaluate all aspects of the 2017 census, the Statistics Division (an administrative Division of PBS), constituted an internal committee consisting of senior PBS officials, which pointed out several loopholes while the census was being conducted, in its published report. The report reveals that the advisory committee constituted by the Governing Council of PBS had shown concern that “the census is not being planned the way it was envisaged [and] none of its recommendations were followed in true letter and spirit … the concerned authorities of PBS had adopted whatever they liked and rejected what was not according to their sweet will” [and] “non-compliance of recommendations by national and international experts, coupled with acute shortage of expert staff and lack of technical expertise, had left the PBS with a number of loopholes.”

The transparency of data collected by PBS is further in doubt, since instead of conducting a technology-based population census (as was done in Bangladesh and Egypt), in Pakistan, it was conducted manually on forms printed over 10 years earlier. Interestingly, just prior to the census, the entire computerised data entry setup in PBS’ Karachi office, which was to do data entry of census forms from Sindh and Balochistan was shifted to Islamabad. Therefore, the possibility of manipulation of the process at a later stage cannot be ruled out. In a recent ruling, the Sindh High Court has indicated that the local bodies elections cannot be held until the official results of the census are released.

As over three and a half years have elapsed since the 2017 census was conducted, many argue that the 5 percent recount is no longer a viable option as births, deaths and migration figures would have changed. According to my calculations, about 8 million people who were not included in Sindh’s population (who most likely shifted to their original province of residence), perhaps seven million were from Karachi and one million from other districts of Sindh. However, conducting another census in Sindh or Karachi alone would not serve the purpose, especially if population of other provinces has been over-reported. Therefore, we may consider three options:

1. Resorting to the 5 percent recount will only determine in which province there was any under- or over-count. Besides, due to changes in population that may have occurred due to births, deaths and migration since 2017, it will be difficult to determine the actual position.

2. The already notified Census Commission may be revived which could review the data of the 2017 census, find out what, if anything, went wrong, and make recommendations to the government on whether to release the data.

3. Conduct a fresh census in early 2022, under the supervision of the Census Commission. Since only Geographic Information System (GIS) maps need to be updated and household lists are available, the exercise could be completed within a month. Since the 2017 census was conducted without proper planning and by a team which was neither professionally trained nor had the experience of conducting a census, its results will remain controversial. Therefore, in the national interest, it may be appropriate to scrap the results of the 2017 census and conduct a fresh census. It may be noted, that while in the earlier censuses fieldwork was completed in about two weeks, the 2017 census took two months, resulting in substantial additional cost. However, since all the household listings are available along with detailed GIS maps, a fresh census could be easily conducted in two weeks in Sindh, using modern technology at a substantially lower cost. Since PBS is short of trained manpower, the task of planning and monitoring a fresh census should be given to the Census Commission, consisting of trained persons and representatives of civil society, with support from the field staff of PBS for execution.