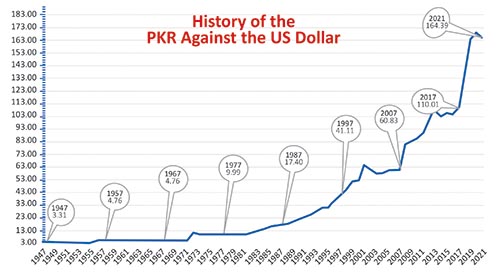

The external value of the rupee has fallen 30 times over the last 50 years (from Rs. 5 to a dollar in 1970 to Rs. 180 to a dollar by end 2021). During the same period, the internal value of the rupee, in terms of buying power, has fallen by 300-400 times. A domestic worker earned Rs. 60 a month in 1970, but today earns over Rs. 24,000 per month. The falling domestic value of the rupee is the result of the political opportunism of our respective governments, who attempt to win over the voters by putting more and more money into circulation without a corresponding increase in productivity or production.

Mansoor, a friend of mine, is a skilful investor in the Pakistani stock market. The other day I congratulated him on the rising value of his portfolio, but to my surprise he replied, “Yes the value of my shares keeps going up, but my wealth, in dollars, keeps going down.” Over the last three years, the average wealth of Pakistanis has halved due to the falling value of the rupee. Whereas, traditionally, Pakistanis have invested in shares, real estate and gold, now the dollar has become Pakistan’s favourite investment. Pakistanis now hold a lot of dollars. The government’s clampdown on dollar investment has not restored confidence in the falling rupee, nor have futile interventions that waste scarce dollar reserves by selling dollars to shore up the price of the rupee. The flight from the rupee has been inventive in finding new havens. Besides, the sophisticated buy Bitcoin, the majority buy cars and motorcycles. The buyer of a new car boasts that its price has risen by 50 percent in the last 12 to 18 months proving how smart an investor he is. He will not accept the fact that it is not the value of the car that has risen, it is the value of the rupee that has fallen.

In 2021, Pakistan with 11 percent inflation had the fourth highest inflation rate in the world, with Argentina being the highest at 51 percent. The hardship imposed by inflation is small when compared with hyperinflation, which has been defined as an inflation rate over 50 percent per month. The five highest examples of hyperinflation in the 20th century are Hungary in 1946, Zimbabwe in 2008, Yugoslavia in 1994, Germany in 1923, and Greece in 1944. The worst cases of inflation in 2020 were, Venezuela at 2,355 percent (down from a peak of 65,000 percent), Zimbabwe at 557 percent (down from its 2007 peak of 100 percent per day with prices doubling every 24 hours), Sudan at 163 percent, and Lebanon at 84 percent. In Hungary, in July 1946, prices tripled each day as the monthly inflation topped 41.9 quadrillion percent and the highest currency bill was 100,000,000,000,000,000,000 pengo. In all these countries the cause was the same: an increasing money supply not supported by a growing economy with higher productivity.

Inflation results from the opportunism of political leaders, who, under pressure from the demands of voters and institutions, increase wages, spending, and money supply without a corresponding increase in production. This short term opportunism, common before elections in democratic nations, or after disastrous wars, has long-term economic consequences. Political leaders, often more attuned to political expediency than an understanding of economics, are led astray by careerist advisors or bureaucrats who misinterpret the great economist, John Maynard Keynes, by quoting increased government spending as the solution, disregarding the context or qualifying principle.

The rupee will continue to lose value domestically for as long as the creation of rupees is not matched by the creation of goods and services, and as long as bad governance, corruption and leakages bleed and dilute government spending.

The rupee will continue to fall against the dollar for as long as the demand for dollars exceeds the demand for rupees. Dollars are needed to pay for imports. Unfortunately, Pakistan has a consistent current account deficit. The combined value of exports, together with worker’s remittances, falls short of the dollars required for imports and debt-servicing. A second, but no less important demand for dollars, comes from speculators who buy dollars and sell rupees to profit from expected devaluation. So far, the consistently falling rupee has proved them right as they make good profit, year after year. These ‘speculators,’ or as Imran Khan calls them ‘money launderers,’ comprise not only corrupt government officials who hide their ill-gotten gains overseas, but also include legitimate citizens such as the nine million Pakistanis working overseas in 115 countries, who every month make decisions regarding whether to send more or less dollars back home. When these overseas Pakistanis anticipate a fall in the value of the rupee, they defer their remittances.

Pakistan is afflicted by a high and unsustainable level of debt, and the twin deficits, current account and fiscal, as its imports grow while its exports do not, and it continues to spend more than it earns. The PTI government claims three major successes in their management of the economy — rising remittances, the EHSAAS program, and its housing policy. The rise in workers remittances of 27 percent in FY 2021 is miraculous at a time when Covid has reduced overseas employment. Pakistan’s Bureau of Emigration and Overseas Employment states that manpower export fell from 625,000 in 2019 to 223,000 in the current year while remittances grew. Has the increased volume of money inflow come from worker’s remittances or some other source, disguised as worker’s remittances? The EHSAAS programme that gives hundreds of billions of rupees yearly to poor Pakistanis clearly does not agree with the old proverb: ‘Give a man a fish and he eats for a day, teach a man to fish and he eats for the rest of his life.’ The revolutionary housing policy of the Imran Khan government has boosted employment and inflation.

Successful developing economies such as China and Vietnam, started their growth journey by prioritising agriculture. Increased agricultural productivity reduces imports, creates exports, and feeds the domestic demand for roti and kapra. The extra wages paid to agricultural labour are absorbed by the extra production of food and clothing, keeping inflation low. The PTI government followed a revolutionary policy of promoting housing rather than agriculture, which certainly gave employment, but when the newly employed construction workers spent their wages, it was not on housing but on roti and kapra, the supply of which did not increase. Pakistan fell into the classic inflation trap of more money chasing a constant or reduced supply of goods. Inflation was inevitable. Furthermore, whereas increased agricultural production reduces imports and even creates exports, you can’t export houses. The PTI priority on house construction certainly gives employment, but produces inflation instead of exports or import substitution, forcing Pakistan to borrow new loans to repay old, unsustainable debt, driving Pakistan towards bankruptcy.

The factors that influence the value of currency are inflation, interest rates, public debt, political stability, economic health, balance of trade, current account deficit and confidence. A tug-of-war for the value of the domestic currency pits the speculators against the State Bank, with the commercial banks in between. The main tools of the State Bank are money supply, interest rates and intervention, when the State Bank spends its scarce reserves on selling dollars and buying the weak rupee. Intervention has more often than not, resulted in reserves drying up before the currency collapse is turned around. Usually, a short-term upswing of the rupee on intervention soon falls back into its downward journey, and the only difference is that State Bank reserves have been eroded.

When central banks try to support the domestic currency against both fundamentals and sentiment, they usually lose out to reality, as finally the forces of gravity drive the domestic currency down. These situations create great profits for those who are not fooled by optimistic statements from government propaganda. The most famous currency speculator was George Soros, known as ‘The Man who broke the Bank of England,’ whose attacks laid low the currencies of UK (1991), Thailand (1997), and Japan (2013). In each case, Soros earned a billion dollars and in his attack on the British Pound, he is reputed to have made a billion dollars profit in one day. An investment of $1000 in 1969 with Soros, would have grown into $4 million by 2000. Economies are vulnerable to attacks when the exchange rate is overvalued and reserves are low. Central banks are frequently tempted to increase interest rates as a defence against attacks, despite conventional wisdom that it is futile to try to defend a highly overvalued currency by high interest rates.

The PTI government promises that the fall of the rupee will be reversed when the IMF programme is restored. But the $1 billion expected from the IMF, and even the additional borrowing that Pakistan may be able to access on the confidence created by the restoration of the IMF programme, will not solve the $26 billion external financing requirements of the current year, when our monthly deficit is over $2 billion. If we can secure the extra debt required, it will only bury us deeper in the hole. It is not a solution, only a postponement of reality. The weak fundamentals of our economy remain unaltered — stagnant exports, growing imports, a growing illiterate and unskilled population, bad governance with bad policies followed by bad implementation, populist politics with payout way beyond productivity increases, a foreign policy that only creates a greater requirement for defence expenditures, and an ever-growing debt. Direct Foreign Investment (DFI), which has proved to be a real solution for countries such as Singapore, Malaysia, Vietnam and even China, has been frightened off by the growing religious extremism that increases political instability in Pakistan. Additionally, investors are warned off by the example of Reko Diq and the lack of pro-business policies or environment.

Today it takes 180 rupees to buy a dollar, what will the rupee be worth in 2022? Conservative forecasters expect Rupees 200 to a dollar by the year end, but if the government’s economic policy continues to disappoint, the rupee could even dip to a range of 220–240 to a dollar. Meanwhile the domestic purchasing power of the rupee will continue to erode, with the current inflation rate of 12 percent, perhaps rising to 15 percent. National debt, both foreign and domestic, would mount as we borrow from Peter to pay Paul.

The writer is a businessman and the author of three books including Muslims: The Real History.