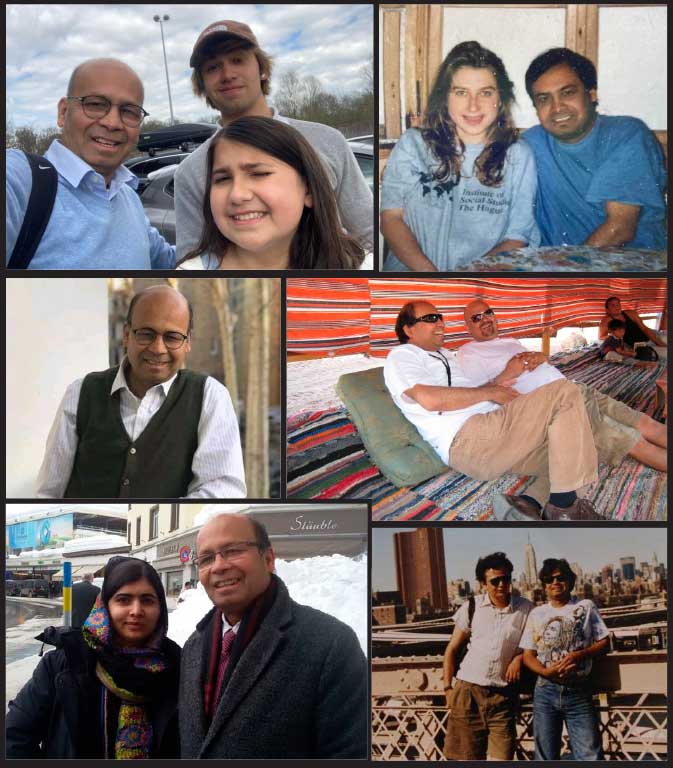

Mentor, friend, family and man of many parts, Khalid Hameed Farooqi’s demise leaves the world a sadder place

By Amir Zia

This is one obituary I never imagined I would write. Only two days before his sudden demise, Khalid Hameed Farooqi and I spent hours together discussing politics, arguing, laughing, remembering our good old days of student politics and making plans to meet again in the next couple of months.

He had come all the way from Belgium at my call to London, so we could spend a few hours together. Over the years, this had become par for the course. Whenever I visited London, Khalid Hameed always took the trouble to come and see me — an old friend, to whom he had introduced the world of student politics.

A star student leader of Karachi’s leftist circles during the 1980s, Khalid Hameed was highly focused, a fiery speaker, a passionate political worker, and above all, a trustworthy, reliable friend and comrade. During the peak of the anti-Gen. Ziaul Haq movement in the early 1980s, Khalid had been imprisoned, beaten up, and even nominated in a murder case. But all this did not stop him from fearlessly forging ahead with his political activities — whether it was organising demonstrations and rallies, pasting posters and chalking anti-martial-law slogans on walls in the dead of the night, or giving vent to his often anti-establishment ideas and opinions in speeches at assorted forums, including educational institutions. He worked tirelessly. In his little frame throbbed a giant’s heart! And all through his life, he remained committed to the ideals he had harboured since his student leader days.

Khalid was not my childhood friend. We had met at the University of Karachi sometime in 1985. And since then our friendship had withstood all our often heated political debates, our recently increasingly conflicting party lines, and our geographical distance (he being in Europe for the last 35 years and I in Pakistan).

I vividly remember our first meeting even after the passage of 37 years. I was a first-year student at the Department of English’s B.A. (Hon.) programme and because I had Mass Communication as one of my subsidiary subjects, I often read newspapers and magazines in its Seminar Room.

Khalid Hameed Farooqi was only Khalid Hameed then and was in his final year of B.A. (Hons.) at the Department of Mass Communication. He initiated the discussion by asking questions about my studies, the books I read, etc. He had ‘Waheed Murad style’ thick straight hair and a mustache at that time. Soon we were joined by a tall, lean and bearded youngster, whom I came to know as Osama bin Razi — an activist and student leader of the Islami Jamiat-e-Talba (IJT). Later, Osama became the IJT’s university ‘nazim,’ and after that held several other senior positions in his organisation. (Now Osama is one of the central leaders of the Jamaat-e-Islami.). Khalid at that time was the General Secretary of the National Students Federation (NSF), Karachi Division. Soon, the three of us were engrossed in an interesting debate about whether the state should be secular or theocratic. Yes, despite all the violence at the educational institutions during the 1980s, there was still space for good discussion between ideological rivals.

Osama and Khalid being class-fellows knew each other well and there appeared to be a lot of mutual respect between them. I, being an apolitical novice at the time, knew very little about them or student politics and its lethality. But in that first ‘historic’ discussion, Khalid’s ideas and mine somewhat converged. That was where Khalid spotted a political worker in me. A couple of days later, he was in my department, noting down my home telephone number (there were no mobile phones in those primitive days) and my home address. We started meeting regularly at the campus and thereafter at my house, where he never came without a gift — usually some old book from the treasure trove of some NSF friends.

There were the works of Maxim Gorky, Syed Sibt-e-Hasan, Shaukat Siddiqui, Abdullah Hussain, Che Guvera, Chairman Mao Zedong, political biographies, the Communist Manifesto and many more. It was often overwhelming, there was too much to read, too much to discuss. In those initial days of our acquaintanceship, Khalid would preach the party line, giving ideological sermons for hours at a stretch. In me, he found a good listener. Meanwhile, my mother would wonder what kind of friends we were. “He speaks all the time,” she said.

But friends we were, and Khalid Hameed knew the art of transforming an apolitical student into a political worker for an organisation that was hounded by the right-wing and so-called progressive rivals alike. Members of the NSF, affiliated with Mairaj Mohammed Khan’s Qaumi Mahaz-e-Azadi (QMA), were not even allowed to wear party badges at that time in the University of Karachi by the rival faction of the NSF-Rasheed Group, which later evolved into the NSF-Gandapur Group.

Khalid was often harassed, even thrashed, by our comrades in the NSF’s rival faction. The hostility among the rival NSF factions was intense, brutal and unforgiving. But this never stopped Khalid from staying steadfast to his beliefs and jumping into political discussions at the first given opportunity, even with bitter rivals.

During these discussions, I recall, he would look his listeners straight in the eye, trying to make a connection, and would lean forward to emphasise each point he wanted to make in his clear broadcast-quality voice. He was the only recognised face of the NSF-Mairaj Group at the Karachi University in those days. We had few other comrades in different departments, but they kept a low-profile, probably to stay out of trouble. When I became an NSF member a few months later, we quietly met in some classroom and following our meetings, dispersed as quietly.

Barring the Urdu Arts College, where our group dominated, the NSF-Mairaj had open units only in a few colleges. In all the other major educational institutions — Dow Medical College, the Sindh Medical College, the NED University and Dawood Engineering College — rival factions of the NSF dominated, while our members kept a low profile. But they were organised in neighbourhood units – the active ones being in Shah Faisal Colony, North Nazimabad, Malir, Landhi, Liquatabad, New Karachi and few others.

After University classes ended, Khalid usually visited neighbourhood units — often travelling on bus from one corner of the city to the other. He would walk for miles to hold individual or collective meetings. His energy, dedication and commitment to the cause was amazing.

Whenever I and a couple of others accompanied him during such stints, Khalid kept our morale up often with stories of Chairman Mao’s long march or Che Guevara’s struggle, making most of the others too ashamed to complain or grumble about our tired feet and hungry bellies. But being the junior-most and an ardent foodie, I have to admit, my protests, difficult questions and cheeky remarks would continue. And so, Khalid would invariably give in and we would stop for a bunkabab at some roadside ‘thaila.’ And of course, being the senior, he would insist on paying, and when the pocket permitted, even buy us a cold drink — which was a luxury. This special treatment, I learnt, was however, mostly reserved to when I — the spoilt one — was part of the long marches.

More than two decades later in New York, in the office of our host — and the third-member of our troika — Comrade Ibrahim Sajid Malick, Khalid announced he would lead a long march on the NY roads, with me in tow. That comprised walking past one roadside café after another, and I could see Khalid was more focused on aimless sightseeing than anything else. After some serious grumbling and protests, he gave in and bought an ice cream from a vendor. This triggered memories of sharing bunkababs in Karachi, and we laughed like mad on the footpath. On the same trip — sometime in 2013 — Khalid had to go and visit his mother in some other city in the US. But of course, two emotional blackmailers — myself and Ibrahim Sajid — didn’t let him go. “How can you leave Amir when he is in New York,” Sajid argued. And it required little pressing to make Khalid stay until I was there. Yes, he was a friend’s friend. Now I realise that we may have been selfish in forcing Khalid not to visit his family as he had planned. But on second thought, we too were one another’s family and our bond was greater than that of real brothers.

Khalid had always been generous, gracious and self-sacrificing with his comrades — whether there was a need for that sacrifice or not. If he was a firebrand and an unflinching political worker when it came to fighting for his ideology, he was a gentle soul among friends and while managing individual relations.

Once I got stuck at the Karachi University hostel for some longish meeting. It was past midnight and no public buses or vans were available. At that time, there were hardly any residential apartments or houses between the six or seven kilometre patch between the University and the NIPA Square. I had no choice but to walk back as staying at the hostel was out of the question because of strict parental rules. Khalid offered to give me company, which was readily accepted. And we two walked, talked and smoked (by the way Khalid was not a smoker, but he would even join me for a smoke for the sake of being better company) all the way, and shared an engrossing conversation. I do not recall seeing anyone all the way on the dark University Road. At NIPA, which was close to my home — Khalid said goodbye and walked back all alone.

Another memorable ‘long march’ was one from somewhere near Hotel Mehran to the Karachi University hostel, though I parted ways with my comrades for my house somewhere near Hasan Square, in Gulshan-e-Iqbal. It was New Year’s Eve, and I dragged my puritan comrade Khalid and a few other friends to the party somewhere. As usual, we had no conveyance — there were no buses at 2 or 3am in the morning and pockets did not permit hiring a taxi or a rickshaw.

In 1987, Khalid left for Holland for further studies. We had long arguments before his departure. Like many comrades, I did not see the point of going abroad for studies and pleaded with him to stay home and carry on with the NSF. But Khalid wanted to end his NSF career alongside the completion of his Masters. He did not want to be counted among those ‘professional student leaders’ who remained a university student even 10 years after completing their studies —moving from one university department to the other, or cooling their heels after taking admission in M.Phil programmes, which they never wanted to complete. Khalid stuck to his decision and proved himself right.

I was among those two or three friends, who bid him farewell at the Karachi Airport. He left to build a new world for himself with a small backpack and a copy of Faiz’s collective works —“Nuskha-e- Wafa” — in his hands. His departure was my personal loss. Other NSF seniors befriended me and kept me going, but I missed Khalid because he was not just my political guru, but also a dependable friend.

In the pre- email and whatsApp days, we kept in touch through occasional letters and very rare telephone call exchanges. After a gap of many years, he started visiting Pakistan off and on. And whether I was in Karachi or Islamabad, Khalid would make it a point to come and meet me. Now even without a party, we considered ourselves part of the party discipline.

Like myself, Khalid also chose to become a journalist while first living in Holland and then moving to Belgium. And he did make a name for himself through his quality reporting and news writing. In fact, he was the first Pakistani journalist working for a Pakistani media organisation, who made a name for himself both, among the Pakistani diaspora and among European stakeholders. He was always on the move — rushing from one country to another. His last assignment before he came to see me was in Ukraine, from where he shared his photos. I asked him to stay safe and refrain from adventure as we were not getting any younger. But Khalid remained young at heart till the end. Always motivated. Always passionate about his work. Always on the move. And always ready for discussion.

In our last meeting — on May 4, 2022 —while we did discuss politics, I think for the first time ever we talked more about our families. Khalid was his usual smiling self. He instantly connected with Tehmina, my daughter and guide in London. That was his first meeting with Tehmina as a young university-going adult. The two agreed to explore the art galleries and museums of Europe later this year.

Khalid shared a few anecdotes about his Polish wife, Ela Wysocka, and the cultural challenges he faced at home, between East and West, especially when his mother visited them. We had a hearty laugh. For Khalid, Ela was the fulcrum of his life, and his two children — Kamil and Maya — his pride and joy. Like previous occasions, he shared how his children, right from a tender school-going age, were trained to be independent and encouraged to play sports and take part in other extracurricular activities. And we had a ‘short march’ — this time on the banks of the River Thames. We casually said goodbye to one another with plans to meet in July. A day later, I heard that comrade Khalid Hameed had passed away. I still can’t believe it.