The acquittal of British-born militant, Ahmed Omar Saeed Sheikh, and three other accused, in the kidnapping and murder case of American journalist Daniel Pearl, has thrown Pakistan’s entire investigation, prosecution and judicial system into a tailspin.

The Sindh High Court’s decision to overturn the conviction of Omar Sheikh and his co-accused in this internationally high-profile case, and the Supreme Court of Pakistan’s subsequent endorsement of the acquittal, raises several troubling questions. The foremost among them is, if Omar Sheikh and the other three men — Fahad Naseem, Salman Saqib and Mohammed Adeel — are innocent, then who will account for the 19 years of their lives lost in prison? And if they are indeed guilty, then how and why is the system allowing them to go unpunished?

On a broader-level, the handling of Daniel Pearl’s murder exposes Pakistan’s entire judicial system, where criminal cases drag on not just for years, but decades, and ultimately, more than 90 percent of the accused convicted by the lower trial courts get off the hook because of poor investigation and prosecution.

It also underlines the grim reality that if securing convictions of suspects involved in heinous crimes like murder and kidnapping remains such a Herculean task, then punishing white-collar criminals involved in financial corruption, money laundering and tax-evasion would likely be next to impossible.

This acquittal is also seen as a test-case for both Pakistan and the newly elected US government. How they handle this tricky affair, which has huge symbolic value for both sides, is a critical question. Washington has expressed outrage, saying that “this decision to exonerate and release Sheikh and the other suspects is an affront to terrorism victims everywhere, including in Pakistan.”

As far as Pakistani investigators are concerned, Omar Sheikh stands guilty of “masterminding” Daniel Pearl’s kidnapping on January 23, 2002 outside a downtown hotel in Karachi.

“There should not be an iota of doubt that it was Omar Sheikh, who met Daniel Pearl at a hotel in Rawalpindi and lured him to Karachi for an interview with Sheikh Mubarak Ali Shah Gilani, an Islamic scholar, who was not part of the conspiracy,” affirms a senior investigator, who interrogated one of the four accused in this case. “But the incompetence of the police officers wrecked this solid case.”

Daniel Pearl, the Mumbai-based South Asia bureau chief of The Wall Street Journal, was in Karachi to research the alleged links between Pakistani militants and Richard C. Reid, the British terrorist, who was arrested in December 2001 for attempting to detonate a shoe bomb while on a flight from Paris to Miami.

“Omar Sheikh planned Pearl’s kidnapping from his aunt’s house in Karachi’s Mohammed Ali Society, along with the three co-accused… but before the kidnapping he went to Lahore, and someone else executed the abduction,” the investigator shares.

Police records state that Omar Sheikh was arrested on February 12, 2002, but according to leaked information, he surrendered himself to the authorities on February 5 in Lahore, due to family pressure.

“A highly intelligent and smart person, Omar Sheikh had a history of being involved in militancy from a young age, when he was a student in London,” says the investigator. “From Bosnia to occupied Kashmir — right or wrong — he stood up for Muslim causes.”

Omar Sheikh was arrested and imprisoned in India for the 1994 abductions of Western tourists in New Delhi; he was among those who were set free in 1999, following the hijacking of an Indian passenger plane to Kandahar, Afghanistan, in return for the hostages.

“Omar Sheikh himself narrated his role in the kidnapping of Daniel Pearl to interrogators, asking them not to touch him (beat him up),” the investigator reveals. “However, Omar Sheikh, did not expect that Daniel Pearl would be murdered by his captors, who included the high-profile Al-Qaeda-linked militants, Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, and Amjad Farooqi. He promised us that he would help secure Daniel Pearl’s release.”

But that never happened. Omar Sheikh did try to get in touch with Daniel Pearl’s captors, who initially avoided his calls, but later told him that the American journalist had been killed.

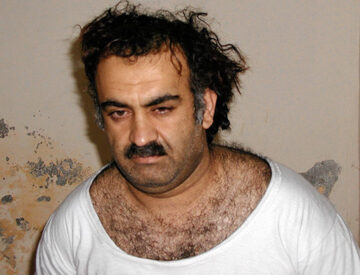

The lynchpin of the Al-Qaeda terrorist network in Pakistan, Amjad Farooqi, who was also involved in at least two assassination attempts on then President Pervez Musharraf in December 2003, was eventually killed in September 2004 in Nawabshah. Khalid Sheikh Mohammed — who beheaded Pearl and was identified through his hand in the video footage, made public by the militants a month after the killing — was arrested on March 1, 2003 from Rawalpindi and handed over to the US authorities. Now he languishes in Guantanamo Bay prison, where he confessed to Pearl’s murder, along with several other crimes.

The investigator’s account of events leading to Daniel Pearl’s kidnapping and murder and the role of militant kingpins involved in this gruesome episode may appear like a fascinating cloak-and-dagger saga, but proving all this in a court of law is yet another story.

Defence lawyers maintain that Pakistan was under severe pressure to deliver Pearl’s kidnappers and killers. Consequently, a swift judgement was passed by the trial court on July 15, 2002 — in less than three months. The court handed down the death sentence to Omar Sheikh for Pearl’s kidnapping and murder, while the other three were given life imprisonment. They were also fined Rs. 500,000 — an amount ordered to be paid to Pearl’s widow, Mariane.

However, in the Sindh High Court, where the appeal dragged on for 18 years, the prosecution failed to prove its case.

Legal experts are of the view that there were many loopholes, weaknesses and contradictions in the case built by the prosecution, which were shred to pieces when the case came up for hearing before the Sindh High Court.

Faisal Siddiqui, the lawyer representing Pearl’s family, however, maintains that he does not know on what grounds the Supreme Court acquitted Omar Sheikh and the other three accused. “Only a short order has been issued… we are waiting for the detailed verdict, which will take some time as it is a complicated and lengthy case.”

A 58-page synopsis of the case filed on January 28, 2021, in the Supreme Court by the petitioner, challenging the acquittal decision of the Sindh High Court says, “Ahmed Omar Sheikh was an international terrorist, specialising in kidnapping for ransom… this context of international terrorism is crucial in adjudicating the present petitions.”

The petition said that the Sindh High Court judgment was “based on a gross misreading of the evidence, disregarding of critical evidence and facts and a gross misinterpretation of the law, resulting in findings which are artificial and shocking.”

For the defence lawyers, the case was fabricated and evidence cooked-up and based on ill-intentions. “At that time, an atmosphere was created where an arrest meant that one is a convict. But fabricated evidence and fake witnesses leave a track,” says Barrister Mehmood A. Sheikh, the Lahore-based defence lawyer of Omar Sheikh. Nothing was proven against Omar Sheikh and the other accused… had this not been the case, they would have never been acquitted by the Sindh High Court and then by the Supreme Court, both of which reviewed the cases minutely.”

Highlighting the flaws and contradictions in the prosecution’s case, Barrister Mehmood Sheikh maintains that firstly, nobody knows who Daniel Pearl went to meet on January 23, 2002 at 7:00 pm.

Jameel Yusuf, the then chief of the Citizens-Police Liaison Committee (CPLC), was the one whom Pearl met shortly before being kidnapped; he appeared in the trial court as the prosecution’s prime witness number two. “He (Jameel Yusuf) only told the court that Daniel Pearl came to see him that day at his office. He also told the court that Daniel Pearl received a phone call at around 5:50 or 5:52 pm, and he overheard him confirming his 7:00 pm appointment. Daniel Pearl received another call at 6:28 pm, and he assured the caller that he would be on time as he was close to the venue. Daniel Pearl left Jameel Yusuf’s office at around 6:45 pm,” Barrister Sheikh quotes from the record of court proceedings.

“After Pearl’s abduction, when the phone numbers from which Daniel Pearl received the calls were traced, it was found that they belonged to one Imtiaz Siddiqui, who to date remains one of the absconders in this case,” says Sheikh.

The biggest blow to the case, according to Barrister Mehmood, was when the prosecution’s prime witness, Nasir Abbas — introduced as a taxi-driver — was found to be a police constable.

Nasir Abbas, in his statement, had said that he dropped off Pearl at the Village Restaurant, Metropole Hotel, from where he was driven away in a white Corolla car by four men, one of whom, he claimed, was Omar Sheikh.

But the defence says that that day Omar Sheikh was in Lahore. Even the police did not mention Nasir Abbas’ name in the FIR which was lodged several days after the kidnapping, and defence lawyers allege that he was a “planted witness.”

Barrister Mehmood asserts that Omar Sheikh was convicted by the trial court just on the “fake statement of the taxi driver.”

Khawaja Naveed, a former high court judge and one of the defence lawyers of Fahad Naseem and Mohammed Adeel, says that another blunder of the investigators and prosecution pertains to the FBI agent Ronald Joseph, who conducted the forensic of the laptop that contained photos of Pearl during his abduction days and the threatening emails. “The FBI agent, in his statement, said that he received the laptop from the American Consulate in Karachi on February 4, 2002 and examined it for six days.”

However, the police in its record, claims that they raided the houses of Fahad Naseem and others on February 11, 2002, arresting them and seizing computers used to send emails and photos. This contradiction in the statement of a prime witness and the police, literally wrecked the case for the prosecution, Naveed adds.

Barrister Mehmood says that the case collapsed because the prosecution did not have any credible piece of evidence, such as documents, a computer or a witness.

Asra Nomani, a journalist and a close friend of Daniel Pearl, who was with Daniel Pearl and his wife during that period, left Pakistan without giving any testimony. Mariane Pearl did not record her statement either, even though Pakistani authorities offered her the facility of doing this from the Pakistan High Commission in London.

Arif s/o Qari Abdul Qadeer, also shown as an absconder, was already acquitted in this case from Faisalabad in 2014, according to Barrister Mehmood. However, the investigators and the prosecution tried to hide this fact from the High Court and the Supreme Court, but copies of this case were also furnished as additional evidence by the defence team.

Even the gory video of Pearl’s beheading did not establish any link between Omar Sheikh and the other three and the murder or Sheikh’s presence at the scene of the crime. The beheading was carried out by Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, who is in US custody, but has not been tried for this offence so far.

A senior investigator, attached to the case in its initial days, maintains that our entire justice system is weak and flawed and benefits criminals rather than victims and their families. “In India, a confession made before the Superintendent of Police stands in court, but here this is not the case. Criminals conveniently change statements when they appear before the judge,” he says.

In his view, the limited period remands also benefit criminals and terrorists. “You can’t break hardened criminals in two or three days or even a week or two… that’s the reason police often hide arrests in the earlier days of any case, but this creates problems of its own and often weakens the case. At least, terror suspects and criminals should remain in custody for longer durations for securing positive results.”

Pakistan also needs to put in place a witness-protection programme in high profile cases, especially those related to terrorism. This is a must. At the end of the day, the Daniel Pearl case has proved to be an embarrassment for the country and, once again, exposed all the weaknesses and flaws of Pakistan’s investigation, prosecution and judicial system. Without carrying out structural reforms, the system will continue to either punish the innocent or favour the criminal. Short-cuts and stopgap measures will not do. The entire system needs to be overhauled. Perhaps, the process of clean-up can begin by holding accountable those top police officers, who received commendations and medals for closing high-profile terrorism cases which, in fact, were never closed. The Daniel Pearl case is a prime example of this grave injustice done to the family of a victim by a grossly inept police and prosecution.