Last month, a few workers were asked to report to the Human Resource (HR) Department of Pakistan Herald Publications Limited (PHPL), the parent organisation of the daily, Dawn. All of them were the non-journalist staff of the newspaper. Once there, these employees — mostly from the Composing Department — were asked to tender resignations right there and then. Permanent employees of PHPL, all of them refused to resign as they had already been forewarned by the PHPL Employees Union not to resign under management pressure.

The Union was aware of the management’s plan, which had already sacked around 40 or more workers from its Lahore, Islamabad and Karachi offices during the last few months.

The PHPL employees were also slapped with a salary cut of 40 percent some two years ago, that has not been restored to this day.

But this is not only the story of Dawn. This has been happening elsewhere in the print and electronic media as well for the last two years. There is hardly any media organisation which has not resorted to retrenchments or imposed forced salary cuts.

With the exception of a few, all television channels, particularly news channels including Geo, are late in paying salaries to their workers by a few to several months. Many television news channels are falling behind in their salary payments by seven to eight months.

And this is not because of the pandemic as the retrenchments and salary cuts of the workers took place way before COVID-19 set in.

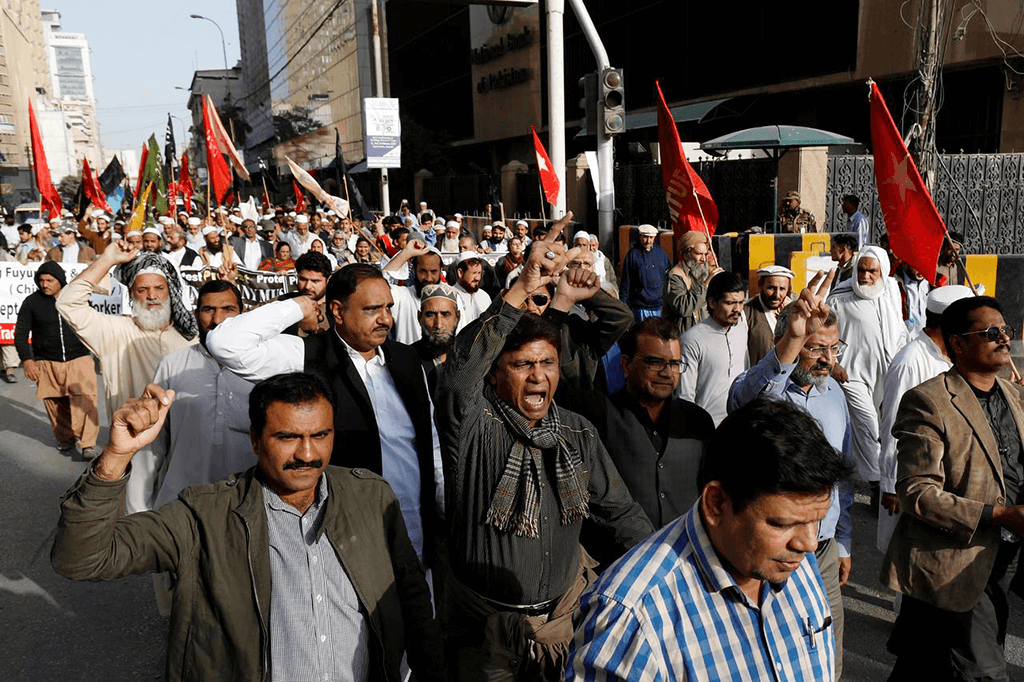

The Pakistan Federal Union of Journalists (PFUJ), an umbrella organisation of all the unions of journalists across the country, believes that around 8,000 workers have been laid off, both in the print and electronic media, in the last two years.

“The media workers are going through a roller-coaster ride at the moment,” says Naasir Zaidi, Secretary General of the PFUJ, “According to rough estimates that we received from our unions across the country, more than 8,000 people have lost their jobs.”

Zaidi holds the government and the owners of the media organisations equally responsible for, what he terms, a “massacre of workers.”

He blames the government for withholding the outstanding advertisement dues of the media industry, amounting to some 2.5 billion rupees, as one cause of the present media crisis. He maintains that the owners used this as an excuse to retrench employees, impose wage cuts and shut down publications, in spite of the fact that now they are regularly being paid their present advertisement dues. “There is a collusion between the government and the media owners on this issue, for their own ulterior motives,” claims Zaidi.

Duraid Qureshi, CEO of HUM Network and former Secretary of Pakistan Broadcasting Association (PBA) that represents electronic media owners, however, disagrees that the reduction in revenues was the only cause of the delay in payment of salaries in television channels.

“I can understand retrenchments, pay-cuts and other austerity measures adopted by the media organisations to balance the shortfall in their revenues, but it has nothing to do with delay in the salary payments,” says Qureshi. “The salary issue is not related to the recession (in the media industry),” he says. “It is merely financial mismanagement and their [bad] intent.”

Economists say that the current media crisis is also the result of a mushroom growth of television channels in the country. “In the absence of real industrial growth, how can one expect advertisements from the private sector?” they say. They argue that the advertisement base is the same, but the shareholders have increased manifold, resulting in a reduction in the share of the advertisement pie.

Shakeel Masood, the present Secretary of PBA, is also critical of the government for issuing more licenses to new TV channels when the market is already saturated.

An insider told Narratives that last month’s revenue of Geo TV stood at around 300 million rupees, which was one of the highest ever. However, in spite of these improving revenues, the owners are laying off workers and staff

He says that around 80 percent of the channels are still on analogue and only 20 percent are digital. The capacity of the analogue platform, according to him, is of 80 channels but PEMRA has already issued licenses to 126 channels, without enhancing its capacity.

“We have asked the government to stop issuing licenses for the time being until it enhances its capacity, but they are issuing more licenses to increase their own income,” says Masood.

This competition, insiders say, has also forced the owners of the print and electronic media organisations to charge much below their officially advertised rates. That is also affecting their revenues.

“It’s a buyer’s market at the moment,” says Masood. “The one who buys air time for us (advertiser), now dictates (the rates of advertisements) and most channels have to accept that.” Even otherwise, he says, the advertising agencies have slashed their rates by 15 to 20 percent over the last two years.

Masood says that the cost of electricity, petrol and the work force have all gone up manifold during the last few years, while revenues have fallen by at least 50 percent. “Media (operational) costs have to be reduced as there is no other option,” he says. According to him, the government is also not ready to cut the “satellite costs,” which, according to him, are very high and a huge burden on channels, given the present financial crisis.

However, the PFUJ says that these are just lame excuses being offered by media owners.

An insider told Narratives that last month’s revenue of Geo TV stood at around 300 million rupees, which was one of the highest ever. However, in spite of these improving revenues, the owners are laying off workers and staff from their television channels, as well as from their print media organisations.

PFUJ’s claim is, to a certain extent, supported by Duraid Qureshi and also by Sarmad Ali, the present Secretary of All Pakistan Newspapers Society (APNS), which represents newspaper owners.

“Things have improved since the last two months and (advertising revenues) are increasing,” says Qureshi. “The consumer companies that had slashed their overall budgets, including advertising budgets, are now doling out advertisements,” he says.

Sarmad Ali agrees: “During the last two months, revenues (of both the print and electronic media) have improved considerably,” he says. “But if we compare the present revenues with 2017-18, they are still short by 25 to 30 percent.”

PBA Secretary Masood claims that business revenues of the TV industry that stood at 45 to 46 billion rupees in fiscal year 2017-18 have dropped to 25 to 26 billion rupees in fiscal year 2019-20. But he agrees that revenues have started improving over the last two months.

“The media was in a desperate situation and costs had to be reduced accordingly,” he says, justifying the retrenchments and pay-cuts. “There was no other option.”

He says that instead of supporting the media industry in these times of crises the government is asking television channels to run 10 percent of their ads for free, such as the COVID-19 awareness campaign. “There is no government support for us like the one given to the real estate and housing sector.”

According to the PFUJ, the media owners are using the crisis only as an excuse to avoid giving print media workers the 8th Wage Board Award, which was announced last year after the owners and media unions reached a consensus on the minimum wages for newspaper employees over the next four years.

Both PBA and APNS believe that if the government agrees to release its outstanding payment of 2.5 billion rupees, the media industry can overcome the crisis.

“Not a single newspaper, including Dawn, Jang or Express Tribune, has implemented the Wage Board Award, although the All Pakistan Newspapers Society (APNS) had signed the Award,” says Zaidi.

The APNS Secretary Sarmad Ali says that newspapers are willing to pay the Wage Board Award but presently they do not have the resources to pay the workers. “Our intention to pay is 100 percent there but the capacity to pay has been reduced.”

Ali says that the reasons for retrenchments, pay-cuts and reduction in newspaper pages were several. Firstly the federal and provincial governments, except Sindh, reduced their advertising budget by 50 percent; this was followed by a recession in the economy due to COVID-19.

The other reasons he quoted are quite interesting. He says that the NAB crackdown on advertising houses and the closure of three to four advertising agencies by them not only scared away the advertisers but also hit the media organisations. “One of the advertising agencies, Midas, which has been closed and its accounts frozen by NAB, owes over one billion rupees to media organisations and we will not be able to recover that money now,” says Ali. “This has also frightened the advertisers.”

Interestingly, Sarmad Ali blames the government’s policy of documenting the economy as another reason for the business crisis. “Pakistan has always had a parallel economy and we should have gone for a documented economy in a phased manner,” he says, adding, “the business houses got scared and stopped investments, particularly in advertising.”

Critics of the PTI government say that it has squeezed freedom of expression and is using advertisement cuts and withholding the media’s long-standing advertisement dues as a tool to force the media houses to toe their line.

Ali says that the government’s advertisement rates have increased only by 70 percent since 2002, whereas the inflation during this period has risen by more than 350 percent. “In real terms, this is the only industry which is earning much less than it was earning a decade ago.”

Both PBA and APNS believe that if the government agrees to release its outstanding payment of 2.5 billion rupees, the media industry can overcome the crisis.

This payment is on account of advertisements issued by the government during the PPP and PML-N tenures. The PTI government is refusing to make this payment on the grounds that these controversial advertisements were issued during the previous governments and hence they are not obliged to pay the arrears of those governments.

“The government’s plea is illogical,” says Ali. “Can the present government refuse to pay the IMF loans that were taken by previous governments or can it refuse to pay the Independent Power Producers on the grounds that those contracts were signed by previous governments,” argues Ali.

Masood also maintains, that the government is obligated to pay the outstanding arrears of the media industry. “Can the government say that the 100-denomination currency notes printed during the PPP government are unacceptable as a currency today?” he argues.

Critics of the PTI government say that it has squeezed freedom of expression and is using advertisement cuts and withholding the media’s long-standing advertisement dues as a tool to force the media houses to toe their line.

However, the PFUJ says it is determined to continue the fight both for the rights of the media industry workers, as well as freedom of expression, no matter what the consequences.

Nasir Malick

The writer is a senior journalist, who has also served as secretary general of the PFUJ