Two significant events impacted the education sector in Pakistan in 2020, shaped intense debate and influenced decisions: COVID 19 and the Single National Curriculum (SNC). In the case of COVID-19, the invasion of the corona virus can be squarely placed as an external factor and Pakistan’s response, as in other countries, was to rapidly move to lockdowns and closures as a containment strategy.

The pandemic declared in the wake of the deadly new corona virus compelled Pakistan to shut down in February and March 2020 and engage in an unprecedented “war against the virus.” This warranted rapid emergency adjustments in all spheres of national life. Cities and towns shuttered down. Schools, colleges, universities, madrassahs and institutes all shut down overnight while administrators and management in public and private sector institutions scrambled to maintain electronic contact. A virtual world opened up and found new entrants, some hesitant new learners and others more savvy. This eerie scene of lockdowns across Pakistan amplified the role of electronic media. TV screens flashed magnetic news and views to information hungry quarantined millions. Covid closures forced education managers and educators to virtually think on their feet about students and teachers, classes and courses, communication and community, textbooks and condensed syllabi. Suddenly, Pakistan was jolted by its lag and late recognition of the fourth information age revolution. 2020 has been a steep learning curve for some and a slippery slope for many.

The SNC aims to sculpt the multi-cultural identities of millions of students into one national identity.

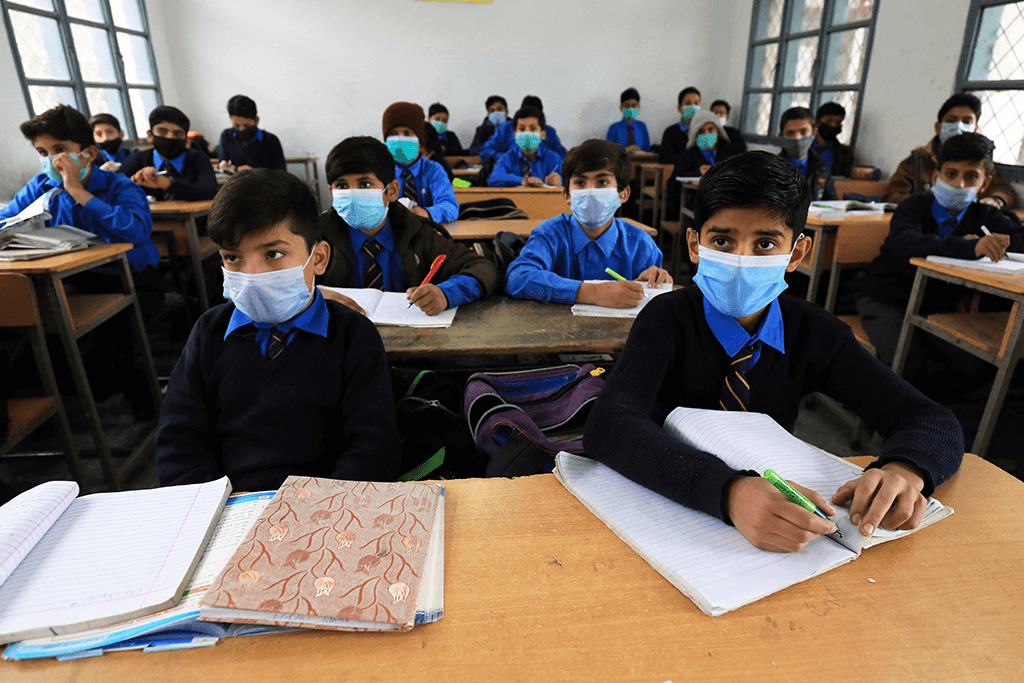

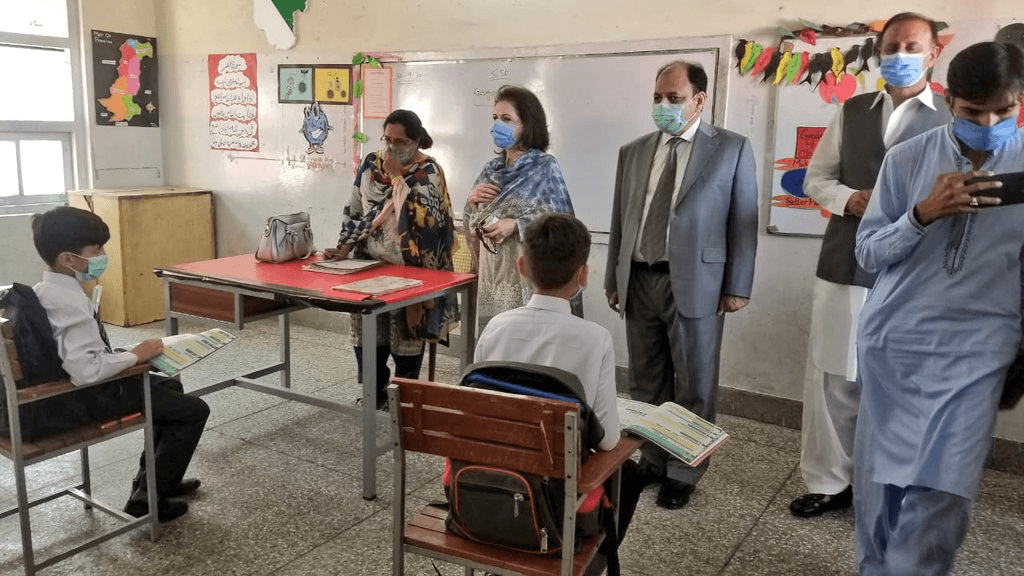

Six and a half months closure of schools, colleges and universities is documented as the longest period of ‘education deprivation’ of the majority of Pakistan’s children. Online learning so glibly espoused by policy makers, education bureaucracy and education providers and advocated as the alternate augmented teaching-learning mode has in fact aggravated the socio-economic divide and created a ‘digital’ apartheid. IT skilled teachers and learners from upper-middle and upper socio-economic strata with access to internet connectivity, iPads, laptops, and smartphones transited to online learning with relative ease.

Public sector schools, mid to low level fee charging private schools, madrassahs and community schools resorted to manual distribution of homework assignments, social media interface and SMS communication. A totally inadequate ‘home learning’ environment deterred student learning. This became acutely evident when students returned to school in September 2020. The alternate days of schooling have further deepened the Covid related learning crisis.

As Professor Dr. Adil Najam, Director of the Frederick S. Pardee Center for the Study of Longer-Range Future, Boston University states, “Pakistan’s future will be determined by the decisions that Pakistan and Pakistanis make. Everything else is context.” This applies to the Covid closure and its varied consequences in the education sector.

The recent Beaconhouse Conference on the Schools of Tomorrow with a session entitled “Single National Curriculum as the Progressive Regression,” is reflective of the debate raging across the country, stoked by two countervailing views. The federal government claims the SNC to be a progressive reform anchored in the notion of social justice, defining it as the instrument that will equalise opportunity, eliminate socio-economic class disparities, promote learning, enhance capabilities, amplify employability and allow for social mobility. Further, the SNC is located in Pakistan’s national and international commitment to the Right to Education, which is indisputably linked to increasing access, retention and completion and to quality which translates into student learning. The SNC presents that “context of learning” through medium of instruction, courses, content, academic and values outcomes. To facilitate learning, the SNC employs national and regional languages as the medium.

Even critics of the SNC concede that employing Urdu or mother language tongue in the early grades will facilitate comprehension.

These ideological aspirations and expectations of societal transformation through a common, unified curriculum taught to every child are closely tied to and derive from the political commitments of the PTI government. As articulated by Shafqat Mahmood, the Federal Minister for Federal Education and Professional Training, the SNC is the vehicle that will level the field between rich and poor and through national/regional/mother tongue instruction enable the muted capabilities and skills of millions of children to find expression and achievement. This proposition of a common culture of learning has a subtext of promoting a defined set of religious beliefs, values and practices through the twelve-year schooling cycle. It also aims to sculpt the multi-ethnic, multi-linguistic and multi-cultural identities of millions of students into one national identity through twelve years of Pakistan Studies. SNC proponents point to content inclusion, claiming that it recognises diversity and pluralism.

These objectives and claims are hotly contested by a body of education practitioners, experts and theorists who advance the argument that education should be about knowledge and skills acquisition that enables students to understand the world through the pure prism of science, technology, maths, language, literature, history and the arts. Education experts use education theory templates that describe this debate in terms other than progressive or regressive; they see the ecology of learning as the centrepiece, the relationship of pedagogy to cognitive development and the theory of knowledge and language as the key that unlocks the door to comprehension, critical thinking, inquiry and problem solving.

They believe that more than ever, in this rapidly changing world, our children should receive education content and learning skills comparable to advanced countries. They are wary of burdening education delivery with a religious, social construct and ideology as it would further exacerbate sectarianism and promote certain tendencies already permeating the national fabric. Their espousal of inclusiveness recommends undiluted content recognising Pakistani’s pluralism and diversity and its religious minorities.

Even critics of the SNC concede that employing Urdu or mother language tongue in the early grades will facilitate comprehension. Global evidence shows that learning outcomes are optimised when instruction is in the mother tongue. On the other hand the relegation of English to a second language is the spectre that haunts the English speaking elite. To them and a significant section of the middle and upper middle class, “nationalisation of the curriculum” is viewed as a regressive measure that will isolate and disadvantage Pakistan’s workforce, which sees English as the passport to a better future. They argue that schooling in English and the option of alternate international education systems equip Pakistanis to compete in the global knowledge economy.

Development policy experts explain the SNC is informed by the irrefutable logic of the language ladder. Simply put, it holds that a child learns best in his/ her native language and the addition of a second or third language can be successfully taught to all children to actualise and maximise their capabilities. If Pakistan wants that every child should have a sound academic foundation, read, write, count and communicate, then the SNC posits a rational approach of instruction in the national or regional language.

Nobel Laureate Amartya Sen’s extensive writings identify the transformative economic, social and personal values of education. He identifies education as the prime agent for developing capability and for emerging from the poverty trap. Sen notes that education deprivation leads to human insecurity, disadvantaged communities and hampers the nation’s ability to become part of the global economy. He cites example of Japan, China, Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Singapore, which invested heavily in education, ensuring that a rigorous national curriculum was developed and delivered to all children in a well-resourced environment. These countries have settled the language issue and use learning achievement of students as the gauge for assessing the performance of their education systems.

Periodic efforts to reform and reconstruct public and private sector education provision have floundered on the complexity of the change process. The absence of a strong national consensus behind the reform measures have constrained previous efforts.

A single intervention is on a slippery slope and needs to be buttressed by multiple synchronised measures and interventions. Determinants of the existing parallel systems differ and state interventions need to be designed for the variances. The SNC requires simultaneous attention to assessment and examinations, textbook choice, development and production, teacher training, systems appraisal focused on learning outcomes, efficiency and accountability for results, enrolment and completion rates, financial resources, improved engagement and governance.

Several consultations have been held by federal and provincial governments, private sector and stakeholders to arrive at a national consensus. Though it seems as nebulous to some, the decision to implement the SNC in a phased introduction from the 2021 academic year has been announced. The coming months will determine the readiness and resolve.