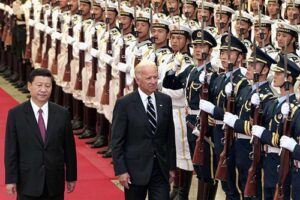

First it was the US-Soviet Union cold war that sucked Pakistan into the so-called jihad in Afghanistan in the early 1980s. Now, it is the US’s singular focus on China as an “ascendant challenge” that exposes Pakistan to extreme pressures because of being a lead partner in the Chinese Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The US, in recent months, has been consciously attempting to woo Pakistan away from Beijing.

There are three factors that define US-Pakistan relations:

A deep-seated mistrust and negative view of Pakistan in the American corridors of power,

America’s predominant focus on counter-terrorism in Afghanistan, and

China posing the biggest challenge to US interests.

One needs to revisit some key events to decipher what is potentially in store for Pakistan as a consequence of being “close to China.”

During his first testimony before the US Congress since the Taliban seized control of Kabul, Secretary of State Antony Blinken (on September 17) rang the first alarm bell for Pakistan.

He said, “We are going to be looking at, in the days and weeks ahead, the role that Pakistan has played over the last 20 years, but also the role that we would want to see it playing in the coming years.”

Blinken resonated the same old narrative that Pakistan “harboured” members of the Taliban, including terrorists from the proscribed Haqqani network — glossing over the fact that the US signed the Doha peace deal with the same terrorists in February 2020.

Then, William Burns, the CIA Director announced (on October 7) the formation of a China Mission Centre (CMC) “to address the global challenge posed by the People’s Republic of China that cuts across all of the Agency’s mission areas,” the CIA said in a statement.

Earlier in April, the entire intelligence community had singled out China as the “single biggest” concern for the United States. This assessment certainly coloured President Joseph Biden’s April 28 speech, in which he referred to China as the “first, foremost ascendant challenge.”

And months before that on October 20, under instructions from Mike Pompeo, former Secretary of State, officials made an entry into the Federal Register that the United States no longer recognised the Eastern Turkistan Islamic Movement (ETIM) as a “terrorist organisation.” Surprisingly, the former Deputy Secretary of State, Richard Armitage, had in August 19, 2002 entered the ETIM into the same Federal Register as a terrorist organisation.

Despite being complete opposites, both moves were fundamentally similar; they were not motivated by ETIM’s reality but, instead, were largely dictated by the U.S. position on other issues, wrote Sean Roberts in the foreign policy magazine, Foreign Policy, in November 2020.

The China Mission Centre will bring together case officers to recruit and train spies, intelligence analysts, including more Mandarin speakers and technology experts and other specialists in a single unit, reported the Wall Street Journal.

The CIA-led CMC will focus solely on China and the national security challenges it poses, calling it the most important threat the United States faces.

“CMC will further strengthen our collective work on the most important geopolitical threat we face in the 21st century, an increasingly adversarial Chinese government,” Burns said, in an official statement released to the media.

It coincides with a sustained assault on the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) through various platforms. In a recent report by the US-based research lab, AidData, researchers identified at least $385bn that 165 countries owe to China for projects under the BRI, according to the British daily, The Guardian.

The four-year study alleges that public balance sheets in these low-to-middle income countries (LMICs) do not reflect the actual semi-private loans. It found that exposure of loans to 42 nations from China exceeded 10 percent of their respective Gross Domestic Products (GDP).

The glaring omission from the study is the fact that it apportions the entire blame for the inaccuracies or hidden loan costs to China. It tends to project these $385 billion as part of the so-called “debt trap” that the West has been crying hoarse about.

In the case of Pakistan, the total Chinese debt amounts to less than 8 percent of the total $122 billion external liabilities, the bulk of which Pakistan owes to the World Bank, IMF and other bilateral/multilateral donors.

With the CMC, the CIA has literally declared an espionage war on China, underlining that it will now open its coffers for anything that may hurt Chinese interests in any way.

Even a cursory look at the developments since the arrival of President Biden betrays a very disconcerting picture for the region as well as for Pakistan itself; the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, under the BRI, essentially sandwiches Pakistan between the conflicting US-China interests in the region.

The CMC, counter-terrorism and continuous pressure on Pakistan to “tame the Afghan Taliban” and support the evacuation of hundreds of Americans still stranded in Afghanistan, remain the cardinal talking points in the US-Pakistan bilateral relations.

Self-serving contradictions and flowing geo-political considerations colour the Pakistan-US relations to a large extent. The China-focus and the aforementioned points reduce this relationship more to a transactional engagement than a meaningful bilateral one rooted in trust and shared ideals. Given the obvious US tilt towards India and the avowed opposition to China and its foreign endeavours such as BRI, there is hardly anything strategic that can cast this relationship in a more constructive and mutually beneficial mode.

As long as the US attempts to stall or undercut China’s outward expansion through the BRI, this will automatically also work against the CPEC, or at least partially undermine it. And this, in turn, will have consequences for Pakistan.

No surprise therefore that in his phone call to PM Imran Khan on October 26, President Xi Jinping urged him not to waver on the CPEC in view of the volatile geo-political circumstances.

“Given that the world is undergoing profound changes unseen in a century, with more sources of turbulence and risks, the two countries should stand together even more firmly and push forward the all-weather strategic cooperative partnership, and build a closer China-Pakistan community with a shared future in the new era,” said the official announcement emerging out of Beijing through the phone call.

At the same time, Xi Jinping reiterated Beijing’s support for Islamabad in exploring a development path suited to its own national conditions and its willingness “to share China’s high-quality development opportunities with Pakistan.” With this also came a renewed pledge by the Chinese President to “jointly build the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) with high quality and strengthen cooperation in… agriculture, digital economy and people’s livelihood.”

How Pakistan navigates this extremely delicate geo-political environment driven by the US-China cold war will be a true test of its tenacity.

The writer is the founder and Executive Director of the Centre for Research and Security Studies.