The quest for peace within the South Asia region has been unending and yet this goal has remained elusive. More specifically, talking about Pakistan and India, the problem has been even more complex. The history of efforts to promote harmony between Hindu and Muslim communities and, later on, nations, dates back to the second half of the 19th century. As the Mughal Empire crumbled, the British colonial rulers singled out Muslims for punishment for igniting a mutiny against them in 1857. Muslim leaders, during that time, started thinking and planning to protect themselves from British wrath and Hindu majoritarianism. The protection from the British was to be achieved by promoting modern (English) education and getting accommodated in the Indian civil service, while the bulwark against Hindu majoritarianism was sought in Muslim identity politics.

The drive for modern education, spearheaded by Sir Syed Ahmed Khan, created some space for Muslims, though it created a schism with the traditionalist Muslims. By and large, the modernists leaned towards a separate Muslim nationhood, while the religious class, for a long time, thought Muslims would be better off within a united India. Many of the religious leaders ultimately did embrace the two nation theory and the concept of Pakistan, a separate homeland for Muslims in India.

The late 19th century and early 20th century were also a defining period for Hindu renaissance. Their leaders, both secular and religious, saw a historic opportunity for Hindus to gain control of the now vast state of India consolidated under the suzerainty of the British and to get rid of both the British and the erstwhile ruling class of Muslims. (Muslims even during that period of decline, were under the illusion that they would recoup their ascendancy). To achieve these objectives, the secular Hindu leaders wanted to coax Muslims into joining the ranks of the Congress Party, while religious leaders advocated various forms of violence and religious cleansing to promote the agenda of Akhand Bharat and Hindutva.

The Hindus thought that this was their moment to capture glory and emerge as a major nation within India and in a world soon to be decolonised. The Muslims, on the other hand, were fighting for their survival and identity. Not only had they been reduced to a minority, though they were still a plurality and formed a big chunk of the population, they feared their fundamental rights would be trampled in a united India. Discrimination and marginalisation were staring them in the face. They made many failed attempts to get adequate or proportional representation in the quasi-democratic system that was being evolved, under the British tutelage, in the provinces and the centre, but their proposals were either quashed or sabotaged.

Throughout this period, 1857 to 1947, the mantra of Hindu-Muslim harmony, sometimes genuine and at others totally spurious, was contrived to hide the realpolitik that influenced bargaining for the determination of the future shape(s) of the state. Bloody Hindu-Muslim riots continued to ruin any chances of common ground amongst the two communities. Incendiary statements added fuel to the fire.

Then the much sought after, unique moment came in 1947, when two, instead of one, states were created: Pakistan and India. It was a time of triumph and celebration for the people of Pakistan, but a cause celebre for Indian Hindus who thought they had lost one part of their empire, their Bharat Mata. Both nations were born in pain and turbulence. Millions of people were forced to migrate, millions lost their lives while crossing new borders. Communal hatred was deepened. In the process, tens of millions of Muslims were left behind in India to fend for themselves. For them there was no Pakistan. Relegated to the status of second class citizens, they were looked upon with suspicion and animus, a fate that the leaders of Pakistan fought against but succeeded in giving nationhood to only one part of the Muslims in the subcontinent.

In 1947, as Pakistan was trying to scramble to its feet, it got a very raw deal from India, in the division of the inherited treasury, assets and armed forces. This was meant to be punishment for the sin Pakistan had committed: the creation of a new homeland. The most stunning blow was the deceitful Radcliffe Award on Gurdaspur district and the occupation of a large chunk of the State of Jammu and Kashmir, whose people had expressed their aspirations to become part of Pakistan because of common faith of the majority of the people, linkages of ethnicity and kinship, ideological affinity and geographical contiguity. More importantly, such a formula for Kashmir was envisaged in and supported by the 1947 Independence Act. The blatant usurpation of Hyderabad and Junagadh also reinforced Pakistan’s sense of victimhood. The chicanery of the last British viceroy, Lord Mountbatten, and the founding leaders of India with which they tried to eviscerate the new state of Pakistan left deep scars on the psyche of its people and successive governments.

The wounds left by these events are deep and painful. The animosity underneath erupts into hot conflicts intermittently but continues to simmer perennially. The Indian posture is characterised by either hubris or paranoia. Pakistan remains defiant and assertive, sending signals that it won’t be stared down. India is bigger in population and area, but Pakistan is a major state in its own right. Pakistan acquired deterrent parity in nuclear power and credible asymmetry in the conventional armed capability.

Is it possible at all to look for peace between these two neighbours, given their volatile fault lines? But before peace come several stages of detente, rapprochement, entente and reconciliation. Initiatives have been taken in the past to broker peace between Pakistan and India, either through third parties or by the two countries directly. The trouble with this approach is that both sides try to jump directly from hot conflict to peace. No wonder such attempts have stumbled and collapsed in the past.

Let’s cast a glance at the efforts that were made since the 1950s. In addition to the exchange of envoys, the first serious effort made at the Liaquat-Nehru meeting in April 1950s culminated in a pact to protect the rights of minorities in both countries and express the desire to avert another war. The next significant endeavour was made during talks between President Ayub Khan and Prime Minister Nehru in September 1960, covering border disputes, financial issues and Kashmir, but failed to produce any results.

Subsequently, in 1962-63, several rounds of talks between the Foreign Ministers of the two countries — Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto and Swaran Singh — foundered on their apparently irreconcilable positions. Pakistan insisted on the international dimension of the Kashmir issue; India stuck to its stance that Kashmir was an integral part of India. However, on the positive side, maps were exchanged for the first time and various scenarios discussed for the division of Jammu and Kashmir on the basis of population, geography and defence requirements. Since there was direct pressure from US President John F. Kennedy for such an engagement, the Indian delegation partly went through the motions to secure approval for US military aid, which was being considered by Congress at that time. In actual negotiations, given its close ties with the US, Pakistan also seems to have overreached its ambitions. The bold diplomatic venture failed.

Shaikh Mohammad Abdullah was sent to Pakistan, in April 1964, as an emissary and mediator by Prime Minister Nehru to explore workability of three possible formulae: an Indo-Pakistan condominium over the disputed state of Jammu and Kashmir; a confederation of India, Pakistan and Kashmir; and a UN trusteeship over Kashmir. Sounds familiar and outlandish? Such proposals are being dusted off and put on the table even today, minus a co-federation. Shaikh Abdullah’s mission came to a halt because of Nehru’s death but historical accounts amply support the contention that Nehru would have agreed to some form of enhanced autonomy for Kashmir, but not to a plebiscite of the whole territory or a territorial settlement per se, because he basically believed that the only acceptable solution of the conflict was, more or less, the status quo.

The other two much vaunted bilateral summits produced the 1972 Simla Agreement and the 1999 Lahore Accord. The first put a weapon in the hands of India to claim that Kashmir was a bilateral issue, not an international issue and the second was used by India to legitimise the ‘sanctity’ of the Line of Control (LOC). Pakistan contests both these interpretations.

For India, major upsets have been the 1963 China-Pakistan border agreement, the 1965 war, the resistance inside IOJK in the 1990s, the 1999 Kargil operation, and the Mumbai attack. They have used them to the hilt to get international support for their position that India is fighting terrorism in Jammu and Kashmir. Not true.

For Pakistan, the list is long: India’s heinous crime of occupying part of Jammu and Kashmir, against the will of the Kashmiris, in 1947, the 1971 war separating East Pakistan, the 1974 nuclear explosions, brutalisation of the Kashmiris in the 1990s, the 2001-2002 armed build-up, the terrorist bombing of Samjhauta Express in 2007, and continuous bleeding, blindings, siege, genocide, and massive demographic changes in IOJK.

The last bilateral round of talks was presided over by President Musharraf and Prime Minister Manmohan Singh from 2004 to 2008. It spawned a raft of confidence building measures, some of them between Azad Kashmir and IOJK such as a bus service for divided Kashmiri families and a truck service for transportation of select merchandise. There was no progress on Kashmir nor was there any intent to achieve this through formal diplomatic channels because a parallel back-door process was underway which produced the so-called four-point Musharraf formula. Prime Minister Manmohan Singh later confirmed that such a “non-territorial’ agreement had been “nearly” reached between him and President Musharraf.

What was the formula? The four points are: (1) demilitarisation or phased withdrawal of troops; (2) no change of borders of Kashmir but people of Jammu and Kashmir will be allowed to move freely across the Line of Control; (3) self-governance without independence; and (4) a joint supervision mechanism in Jammu and Kashmir involving India, Pakistan and Kashmir. The formula and the composite dialogue process fell apart following President Musharraf’s departure.

After Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s rise to power in 2014, it became extremely difficult to resume bilateral talks in any form. The Modi government borrowed the Congress Party’s playbook on Kashmir, but flaunted its ultranationalist posture on the issue with aggressive rhetorical flourishes. After many hiccups, a new bilateral dialogue process was revived in 2015 with a 10-point agenda. The agenda items were: peace and security, confidence building measures (CBMs); Jammu and Kashmir; Siachen; Sir Creek Boundary dispute; Wullar Barrage/Tulbul Navigation Project; Economic and Commercial cooperation; Counterterrorism; Narcotics control; People-to-people exchanges; Humanitarian issues; and Religious tourism. The bilateral process envisaged never took off.

Many international leaders have also tried to defuse tensions and bring peace in the region. President Dwight Eisenhower urged both India and Pakistan to resolve major outstanding issues and offered to designate a special envoy for the purpose. President John F. Kennedy picked up the thread during his presidency and in fact he was the force behind the Bhutto-Swaran Singh talks. The Rann of Kutch Accord was facilitated by British Prime Minister Harold Wilson; and Russian Prime Minister Alexei Kosygin hosted India-Pakistan talks in Tashkent following the 1965 War. There are many other examples, for instance President Bill Clinton interceded during the 1999 Kargil war to avert an impending nuclear conflict between the two nations. And in 2019, President Donald Trump offered to mediate on Kashmir but his overture proved to be a damp squib. A third party — the World Bank — successfully brokered the Indus Water Treaty.

Multilateral diplomacy on Pakistan has been an abiding track on Kashmir, especially in the initial phase of the dispute. The UN Security Council started its deliberations on the issue in January 1948 and by 1957 it had passed a dozen resolutions mandating a plebiscite to ascertain the wishes of the people of Jammu and Kashmir. The UN Commission for India and Pakistan was established to prepare the ground for a plebiscite. Four UN mediators — General McNaughton, Joseph Korbel, Sir Owen Dixon and Frank Graham — all made strenuous efforts to bridge the differences between India and Pakistan and persuade their leaders to help the UN hold a plebiscite. Pakistan was ready but India was not. The latter just wanted to bide time to perpetuate its occupation of the territory. The rest was merely political dissimulation on its part. Since 1972, however, the UN has taken a hands-off approach to the Jammu and Kashmir issue, restricting itself to issuing bland, vapid statements to the effect that it would be ready to mediate if both India and Pakistan agreed. This condition kills UN mediation ipso facto because India has vowed, post-1972, not to invoke or involve the UN on Kashmir. The presence of the United Nations Military Observer Group in India and Pakistan (UNMOGIP) is the tangible vestige of UN presence, which is hectored by India at every step and its presence tolerated grudgingly.

Post-August 2019, Pakistan, with the help of China, was able to arrange three informal meetings of the UN Security Council. The last authoritative pronouncement on Kashmir was made by the Council in 1998, following nuclear tests by the two countries, in the Operative Paragraph (OP 5) of its Resolution 1172: “Urges India and Pakistan to resume the dialogue between them on all outstanding issues, particularly on all matters pertaining to peace and security, in order to remove the tensions between them, and encourages them to find mutually acceptable solutions that address the root causes of those tensions, including Kashmir.” Even in this resolution, the UN does not mention any specific responsibility for itself but it just “Welcomes the efforts of the Secretary-General to encourage India and Pakistan to enter into dialogue (OP 6).”

Now comes the hard part. After India’s invasion, siege, and communication blockade of IOJK in August 2019, the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) -Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) government in India has radically altered the situation on the ground. The occupied part of Jammu and Kashmir has been torn asunder into two Union Territories (read federal capital territories) and the Delhi regime has abolished the constitution of the disputed state, banned and taken down its flag and dissolved the Assembly — all without the consent of the people. IOJK has been turned into a slave state. Article 35-A of the Indian Constitution has been repealed to take away Kashmiris’ exclusive rights to citizenship, ownership of land and property, jobs and educational scholarships. Everything is up for grabs. Land is being confiscated to build illegal settlements in the colonised state. More brazenly, millions of Hindus from India have been given new domicile certificates for illegal settlement in the occupied state to shrink the Muslims majority. Add to that the continuing carnage of youth, crimes against humanity, and thousands of detainees without access to justice. This is a dire situation.

Another potent development poses an existential threat to Pakistan that cannot be swept under the carpet. And that’s the rise of Hindu fundamentalism and violent extremism, accompanied by the unbounded zeal of the followers of the RSS to stoke Hindu nationalist sentiment against Indian Muslims, persecute them systematically and forcibly proselytise the most vulnerable among them. Pakistan too is a target because it allegedly catalysed the ‘vivisection’ of a united India. India is using all instruments of proxy war, now fashionably called hybrid war, against Pakistan — subversion, terrorism, economic sabotage, incitement to religious hatred, and information warfare. Every Muslim in India is suspected of disloyalty or a hidden inclination towards Pakistan. What’s more, anti-Pakistan, anti-Kashmir and Islamophobic platforms have proved to be a bonanza to the ruling party in electoral politics. The rhetoric of war against Pakistan is common currency.

It is against this grim background that the quest for peace with India is being set forth in recent months. Of course, peace and stability in the region will remain a resolute goal until it is achieved and Pakistan has been pursuing it for decades. Let’s us do some fact checking.

Kashmiris in the IOJK have borne the brunt of Indian atrocities, including systematic genocide since 2019. In this dark hour of suffering, the only country they have been looking towards is Pakistan. The leadership, parliament and people of Pakistan vowed that they would save Kashmiris from Indian oppression by using all means, especially political and diplomatic tools. It was Pakistan that upped the ante and raised the stakes in the United Nations and around the world. As the worst crimes continued to be committed in the IOJK, Kashmiris pinned their hopes on Pakistan’s diplomatic efforts. Demonstrating its angst and anger, Pakistan slapped diplomatic and economic sanctions on India, which were more like a boycott.

Simultaneously, until recently, some 1.5 million civilians living along the Line of Control suffered from frequent attacks by Indian troops using mortars, artillery and even cluster munitions.

Uncharacteristically, this time around, after August 5, 2019, initially, the international media, Western parliaments and human rights organisations vehemently supported Kashmiris’ rights in IOJK, called out India and gave a fair hearing to Pakistan’s perspective. The diaspora communities internationalised the Kashmir issue by taking it to the streets and squares and parliamentary chambers. Enormous international space was created for the Kashmir cause and demands for the protection of the rights of the Kashmiris were turning into a crescendo in the months following the shocking Indian actions during and after August 2019. But then, regrettably, because of domestic infighting and a series of momentous international developments, the attention towards Kashmir blurred and the momentum petered out.

Despite international clamour on the deteriorating situation in the IOJK, there has been this stubborn and unstated resolve at the UN Security Council and amongst powerful nations not to use any diplomatic levers to resolve the Kashmir dispute or to change the status quo. This inertness is primarily caused by the fears that any attempts to resolve the issue could push India and Pakistan to the brink of a nuclear war and the Western nations’ close strategic and economic relations tied with India within the spectrum of Delhi’s espoused role of containing China would be imperilled.

Pakistan’s economy has been hit hard by the Covid-19 pandemic, but it seems to be turning a corner with a recent forecast of a GDP growth rate of 4 per cent. We hope that in the coming years it will fully bounce back and gain its full potential. The putative linkage between the underperformance of our economy and Kashmir is laboured and specious. Show me any specific allocation of resources for Kashmir in our budget. Kashmir cannot be artificially and thoughtlessly linked to the overall defence budget which remains a constant for effective security of the entire state and will continue to grow, with or without Kashmir. The economic malaise is caused not by Kashmir but by mismanagement, non-payment of taxes by a growing middle class, now estimated to be 40 per cent of the population or roughly 82 million people, non-competitive export industry and services sector, rent seeking, crony capitalism and corruption. The problems of Pakistan’s economy are internal, not external, and definitely not related to financial allocations for national security institutions or Kashmir.

The winds of prosperity are not likely to blow from the eastern border. For rapid economic growth and coming out of the vicious cycle of heavy debts and never-ending structural reforms, we should develop human capital, rely on our national resources and tap into the East Asian, West Asian and African markets.

Despite international civil society’s censure and condemnation, India has moved ahead on Kashmir undeterred, with dogged impunity, in full confidence that the Western bloc, for its own strategic reasons, would continue to provide cover for the Indian crimes against humanity and genocidal practices in IOJK. It is really counterintuitive that while Pakistan and the Kashmiris have been wronged over the decades, India demands redemption from us on trumped up charges of acts of terrorism and unabashedly seeks indemnity for its own war crimes in IOJK.

India is seeking exceptionalism, but it is not exceptional. It is not invulnerable and impervious to scrutiny. It therefore desperately needs a nod, a gesture from Pakistan to cover its illegal acts in IOJK. The best forms for India’s purpose would be a bilateral summit, a ministerial photo-op or acknowledgement of an ongoing back channel. All of this would send a signal, from our side, inadvertently, that Pakistan is ready to live with the changes in IOJK. Secondly, Kashmir has, directly or indirectly, fuelled dissent in India and has fanned communal hatred against Muslims. This has costs for India. Thirdly, normalisation of relations with Pakistan will help India as it seeks a permanent seat in the UN Security Council, a bid likely to be backed as strongly by the Biden Administration as it was by the Obama Administration.

There is also this push from new US Administration, supported by influential Gulf states, to persuade Pakistan to let bygones be bygones and despatch Kashmir to the back-burner or at best work at a face-saving, cosmetic formula. The US believes that in order to retain its strategic salience in West Asia and implement its Asia-Pacific agenda, it must have a compliant Pakistan that is on its side and not actively hostile to India. Pakistan has its own constraints because the bulk of its defence supplies and a major economic lifeline — in the form of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) — come from China.

Making peace with India at this juncture, while India is relentlessly pursuing its audacious agenda on Kashmir, is like walking on eggshells. The clear answer should be, and is, that there would be no normalisation at the expense of Kashmir. Restoration of the 2003 ceasefire arrangement between India and Pakistan along the Line of Control is a step in the right direction as it has saved lives and reduced tension. But we should move with extreme caution when it comes to further steps. India must reinstate Occupied Jammu and Kashmir’s disputed status in accordance with the UN resolutions and restore Kashmiris’ inherent rights recognised in Article 35-A of the Indian Constitution. Conventional wisdom and our long, bitter experience suggest that India will do neither. After all it has grabbed IOJK with full military force to market it as a trophy to the hardline Hindu electorate before the next general election in 2024.

Post-August 2019, Pakistan had gained some international traction on Kashmir and for several months it had become an international issue. That window is still open because of the gravity of the situation in IOJK. India is feeling pressure, which it wants to neutralise by a facade of engagement with Pakistan, which will produce no results. Pakistan should not surrender that space. Once the international dimension of the issue vanishes, it will be very difficult to revive it. We have seen this happening before.

Pakistan should seriously conduct a proper performance audit of previous rounds of talks on Kashmir before plunging into a new one. In the past, every incumbent leader in Pakistan had the illusion that he alone had the magic wand to tame or outwit the Indians. Let’s not repeat that mistake.

Our support to Palestine has been a central plank of our foreign policy, but it should never be used as a surrogate for Kashmir or for vicarious catharsis, while every pathway to mitigating the harrowing and unfolding tragedy in IOJK appears to be blocked.

Pakistan has not been able to help Kashmiris militarily in the aftermath of August 2019, though a full-fledged war had been imposed in the occupied territory. What besieged Kashmiris have right now is the anger of the Pakistani nation on Indian atrocities and diplomatic outreach by the Pakistani state. These two supportive constructs in Pakistan’s policy should not be scuttled. We are confident that our capable diplomats and negotiators will not draw the curtain on their well-considered political strategy on Kashmir that impinges directly on Pakistan’s national security.

There is a double whammy in seeking peace with India without taking into account the repercussions of India’s scorched earth, colonial policy in IOJK. For one, India would misinterpret our quest for dialogue to the Kashmiris by telling them that Pakistan is deserting them. Kashmiris’ displaced anger directed towards Pakistan may run amok, serving India’s interest to drive a wedge between Pakistan and the people of Jammu and Kashmir.

Kashmiris must be part of any diplomatic discourse or process not only because they are the central party to the dispute but because no formula crafted without their consent is likely to succeed or assure an end to the turbulence in the region. The Good Friday Agreement was accepted by all; hence it survives. And this prescription is good for all unresolved issues.

Our calling beckons us to move to our national axis which is unfinished without Kashmir. Kashmir is not the Albatross around our neck, but the missing piece of our nationhood, sovereignty and security. We do not oppose diplomacy or talks. On the contrary, for the people of Jammu and Kashmir and Pakistan the preferred option for the resolution of the Kashmir issue is multilateral diplomacy. All we ought to do is to avoid an ambush masqueraded as a diplomatic overture. Of course, there is a compelling rationale for engagement with India but not one that foists a fait accompli on Pakistan and IOJK. A cold, rational, strategic calculus should guide our initiatives and actions.

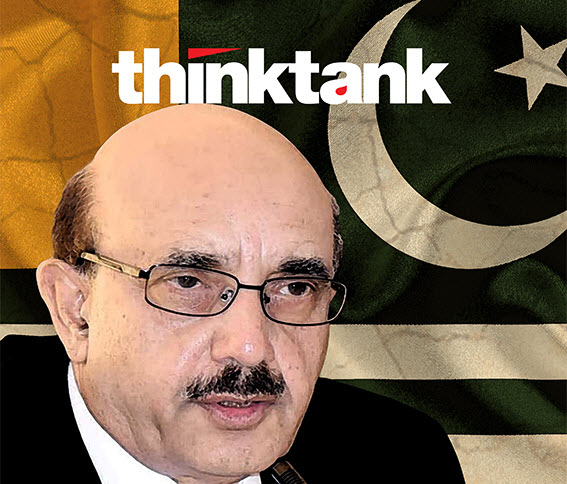

The writer is the 27th President of Azad Jammu and Kashmir.